Heidi Gilman, 17, a high school senior in Northern Virginia, had long dreamed of attending the University of California, San Diego.

She envisioned herself studying politics on the coastal campus, enjoying sunny weather and visiting nearby family.

But after President Donald Trump was re-elected last autumn, and as she became disillusioned with American politics, she began to ask herself, “Is this how I want to spend the next four years of my life?” The question prompted her to look elsewhere and apply to Trinity College Dublin — a place where she said she could learn about politics from another country’s perspective.

Since Trump’s inauguration in January, universities across the US have become targets of a new White House agenda to change higher education in the country. Federal funds supporting research have been cut and programmes that encourage diversity on campuses have been upended.

While international students face an urgent need to find universities that will sponsor their visas and allow them to continue their studies, some US citizens are leaving for what they believe are better opportunities.

It’s not clear whether enrollment will be affected for the coming academic year, but The New York Times asked US students who were considering schools abroad next year what had motivated them to leave. Most of them said they sought a less tumultuous backdrop to their college experiences and were motivated by various federal policies and actions in recent months.

After Gilman saw the news of firings at the education department and students being taken into custody for potential deportations while at school, she began to worry about the direction of the country. “Do I want to be worried about these things, or do I want to be focussed on getting an education and learning?”

While some students disagree with the Trump administration’s intrusion into college campuses, other Americans worried about the rise of antisemitism and intolerance on college campuses are pleased to see the shake-up.

For most students, other practical factors such as living costs, financial aid and location weigh heavily in college decisions. Other US students — motivated by the political environment, funding cuts to universities, better career opportunities or less expensive tuition abroad — are heading to countries such as Canada, the UK, the Netherlands and beyond.

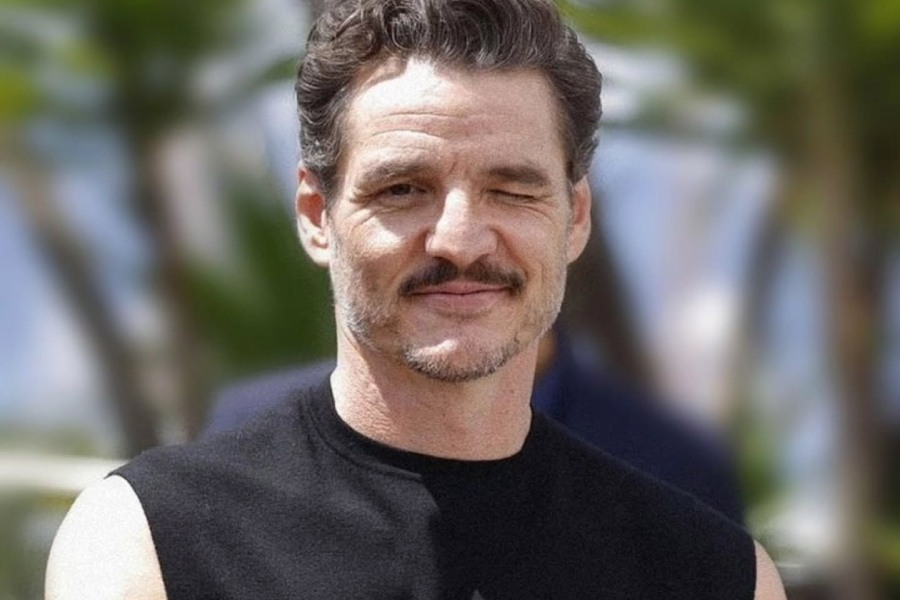

In mid-April, Jessamine Jeter, 27, a doctoral student at the University of Washington in Seattle, was informed that the professor who oversees her research on indigenous languages in the Brazilian Amazon was leaving for a position at McGill University in Montreal.

McGill extended Jeter an offer to attend as well.

After spending a couple of weeks considering the offer, she realised there was little funding left in the US to continue the linguistics work she is most passionate about and decided she would most likely follow her professor to the Canadian institution. “It’s been very difficult,” Jeter, who grew up in Washington state, said.

“I love the department so much, but thinking about opportunities, career wise and research wise, I’m losing a lot of those by staying here.”

As US students and faculty lose research funding or have their acceptances rescinded because of budget cuts, some universities in other countries have made attempts to court them.

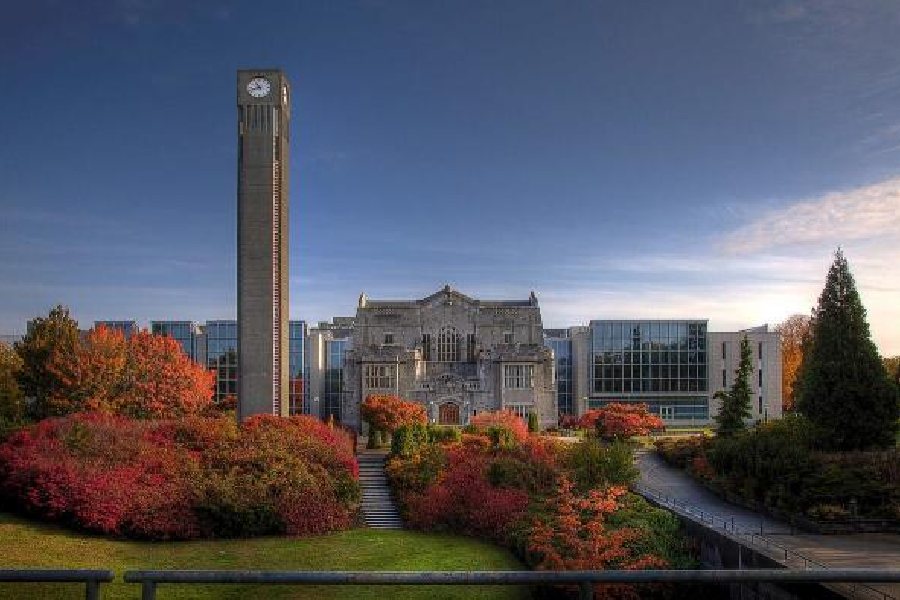

The University of British Columbia, for example, reopened applications for some US graduate students in April.

Gage Averill, the provost at the University of British Columbia Vancouver, said the institution recognised that US students were “having to make decisions on the fly” when it came to choosing their next steps in academia.