President Donald Trump’s 50% tariffs landed like a declaration of economic war on India, undercutting enormous investments made by American companies to hedge their dependency on China.

India’s hard work to present itself to the world as the best alternative to Chinese factories — what business executives and big money financiers have embraced as part of the China Plus One strategy — has been left in tatters.

Now, less than a week since the tariffs took full effect, officials and business leaders in New Delhi, and their American partners, are still trying to make sense of the suddenly altered landscape.

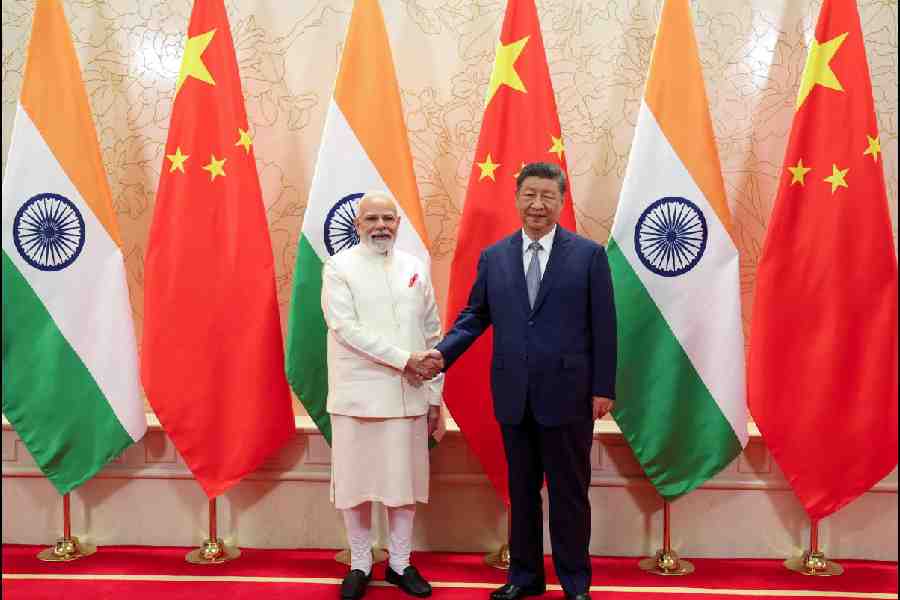

Just how much things have changed was evident from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China over the weekend to meet with Xi Jinping, China’s top leader. Trade and political relations between India and China have been strained, at times severely, and it was Modi’s first trip there in seven years.

The China Plus One approach has been critical to India’s budding ambitions to become a factory powerhouse. Manufacturing growth, especially in high-end sectors such as technology, was seen by India as addressing chronic problems such as the underemployment of its vast population of young workers. Now pursuing that path, without the support of Washington, and in potentially closer coordination with China, promises to be even more difficult.

Trump’s tariffs are already causing dislocation in supply chains. India has been rendered far less enticing to American importers. Companies can go to other places for lower tariffs, such as Vietnam or Mexico. A U.S. court ruling, which on Friday invalidated the tariffs but left them in place while Trump appeals, did nothing to repair the rupture between the countries.

The “Trump shock will reduce manufacturing export growth and kill even the few green shoots of China Plus One-related private investment,” four Indian economists, including a former chief economic adviser to Modi, wrote in an Indian newspaper last week.

India still aspires to become one of the world’s three largest economies. It is currently fifth and on pace to overtake Japan soon. If the United States won’t help or, worse, gets in its way, India has no choice but to get closer to China, even as it holds to its goal of becoming a stronger manufacturing rival to its giant neighbor.

“China Plus One, minus China, is too difficult,” was the wry reaction of Santosh Pai of the New Delhi law firm Dentons Link Legal. Pai is near the center of gravity: He set up a practice advising companies from all three countries. “They have to reconcile themselves to seeing China as part of the supply chain,” he said.

But the India-China relationship is as complicated as they come. The countries have armies ranged against one another, across their disputed borders in the Himalayas. A decade of cross-border incursions culminated in June 2020 with hand-to-hand combat that killed at least 24 soldiers. But the economic conflict was already burbling under the surface.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, with its stock market nose-diving, India was alarmed to discover that China’s central bank had quietly acquired 1% of one of India’s biggest private banks. India responded by blocking many forms of investment from China. Eventually it kicked out most Chinese venture capital from its tech startup hubs and barred more than 200 Chinese apps, including TikTok.

China has an even larger arsenal of economic weapons. It has restricted India’s access to rare earths and dozens of other technologies that India needs to keep its factories running.

“These past five years, with the stalemate, China has progressively weaponized everything,” Pai said. He counts 134 industrial categories that China controls, creating Indian vulnerabilities.

But Trump’s weaponization of economic policy has dealt a much crueler blow to Indian companies. Businesspeople in Moradabad, a center of handicrafts and light industry less than 100 miles from New Delhi, said they felt betrayed.

“Most people are still in shock,” said Samish Jain, a manager at Shree-Krishna, a family-owned company that makes a full range of housewares, 40% of them bound for the American market. Until the final deadline came Aug. 27, he said, “everyone was like ‘no, this isn’t going to happen.’”

Now that it has happened, Jain is groping for a way out, along with the many Indian suppliers and American customers of his company and thousands of others. India’s government is announcing programs to help businesses financially, but Jain said they would not be enough to keep Shree-Krishna from having to make hard choices.

“I have people working in my factory since when my dad started this business 30 years ago,” Jain said. “We can’t just let them go.” He is trying to find new markets for their goods, in the Middle East, Europe or India itself. But so is everyone else in his predicament.

Modi came to China under tremendous pressure. India’s marketing of itself as an option for multinationals that want to move production out of China was not lost on the Chinese leadership.

“I think both are going into this as a dilemma because it’s fundamentally a competitive relationship,” said Tanvi Madan, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

Even before Modi’s diplomatic visit, India and China were talking about resuming direct flights between the countries and opening trading posts along the border. The meeting in Tianjin, China, on Sunday, didn’t produce any joint agreements, but India’s Foreign Ministry said that Modi and Xi made plans “to expand bilateral trade and investment ties.”

China has at times made it hard for Taiwanese giant Foxconn to send Chinese engineers to India. Foxconn is the main contract manufacturer for Apple, which has become a touchstone for India’s China Plus One approach. Apple still makes a majority of its iPhones in China but has in recent years shifted more of that work to India.

And on its side, India has been refusing to grant some business visas to Chinese investors.

China is eager to invest in India. Now, national security concerns notwithstanding, India will be hungrier for a new inflow of foreign exchange as its $129 billion trade in goods with the United States unravels.

Foxconn is an example of the tricky spot Modi is in, and also of how India could benefit from warmer ties with China.

In June, Big Kitchen, a Chinese restaurant catering to East Asian expatriates working at the newest iPhone plant near the Indian city of Bengaluru, was desolated. A Foxconn employee from Vietnam, sharing a dish of twice-cooked pork, grumbled that his Chinese colleagues were stuck outside the country, leaving him and a smaller number of non-Chinese engineers to train thousands of new Indian workers.

If India makes it easier for China to invest in Indian companies, China could make it easier for India to take a few steps in its direction.

“We want the Chinese to come in,” said Pai, the New Delhi business lawyer. India would be “grateful,” he added, for some kinds of Chinese investment, especially in technology, because it would bring jobs to India.

China and the United States have been India’s two most important trading partners, each indispensable in some ways. But India is relatively small fry to both, in terms of imports and exports.

If this were a love triangle, India would be the jilted lover. Trump has, with the 50% tariffs and his advisers’ hostile remarks, dumped it. That casts a shadow over Modi’s new approach to Xi.

The direction is clear, even though important details are not. “China has not showed its hand yet,” Pai said. By contrast, “India has a huge dependency on China for imports. It’s clear what India wants.”

The New York Times Services