Bappa Ghosh was certain that his name would not appear in the draft electoral rolls for Bengal published on Tuesday, 16 December, by the Election Commission of India.

Ghosh, 38, has no way of establishing any family link to the 2002 voter list, which the poll panel has decided as the year to cross-check with in the special intensive revision (SIR) of electoral rolls exercise underway in Bengal; 2002 was when the SIR exercise was last done in the state.

Ghosh crossed over into India from Bangladesh in the early ’90s as a child.

“We used to host Kali Puja in a ground that we owned in Bangladesh,” he told The Telegraph Online. “One time, miscreants vandalised the puja and thrashed my father. Shortly after that, he sent me to India to live with a relative.”

His parents were supposed to come to India too, but passed away of natural causes while still in Bangladesh. Ghosh, who does odd jobs for a living, grew up working at a tea stall in the Bongaon area of Bengal that borders Bangladesh.

Ghosh is married, settled, and over time has managed to procure identification documents in India, including a PAN and Aadhaar card.

He has voted before, but he is scared that if his name doesn’t make it to the voter’s list this time his existing identification documents will become null and void, making him “illegal”.

That is why he is applying for citizenship under the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) enacted by the Narendra Modi government, which clears the way for Indian citizenship for minorities persecuted from neighbouring countries – from all faiths except Muslims.

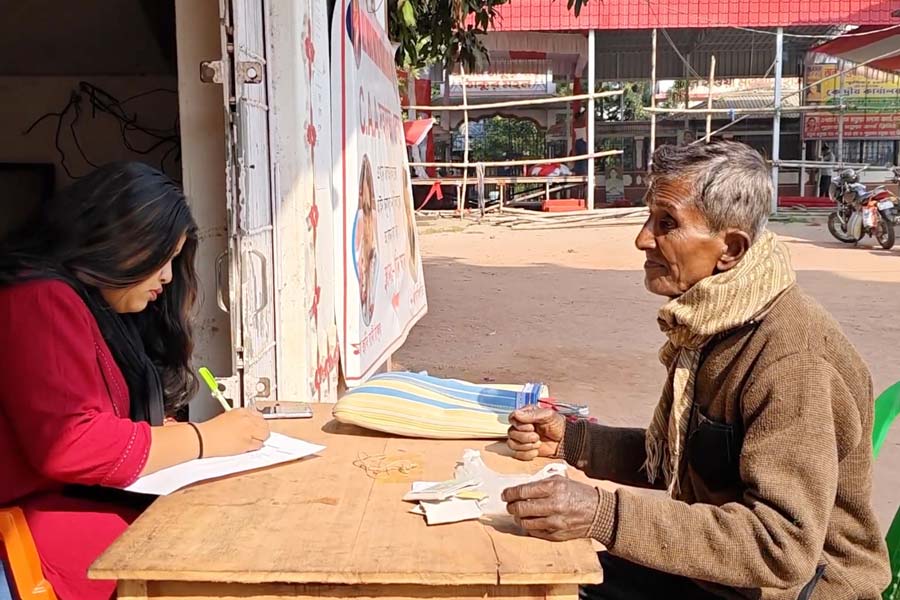

On Tuesday, Ghosh carried his documents in a thin plastic packet to one of the makeshift camps that dot the lanes around Thakurbari in Thakurnagar, around 65km northeast of Calcutta, where Matuas from Bangladesh can apply for Indian citizenship under the CAA, and also get a religious “identity card” stating that they are Hindus.

The Matua sect of Namashudras – a Dalit community – was set up by Harichand Thakur in present-day Bangladesh in the 19th century. Millions of them have immigrated to India – many even before Bangladesh was born – over the years to escape persecution as well as in search of a better life.

They are the Bangladeshi “intruders” that Bengal does not have a problem with; Matuas make up the second-largest Scheduled Caste (SC) community in the state.

Every party in Bengal, including the BJP, Congress, CPM and the ruling Trinamool, tries to woo the Matuas in every election with the promise of fighting for citizenship rights for those who do not have.

SIR or citizenship test? Fear blurs lines

The professed aim of the SIR exercise is to weed out ineligible names from the voter lists, not to identify illegal aliens. But Ghosh isn’t the only one scared that losing voting rights would mean deportation.

According to the draft voter’s list released by the Election Commission after the SIR in Bengal, the Matua-dominated regions have thousands of names that have not been mapped to anyone in the 2002 list. Bongaon Uttar and Dakshin have 26,053 and 18,562 non-mapped names respectively, while the Ranaghat Uttar Purba and Ranaghat Dakshin constituencies have over 15,000 non-mapped names.

Several members of the Matua community expressed their fear and concerns over their identification in India with the SIR underway. Almost all of them, whether they came before 2002 or after, don’t have links to the 2002 list.

Those who have voted before but whose names have not made it to the draft voter list after the SIR will be called for a hearing where they will have to furnish at least one document from a list that does not include PAN or Aadhaar.

The accepted documents include birth certificate, passport, Madhyamik (Class X boards) or any other certificate of educational qualification, residential certificate issued by any organisation under the state government, forest right certificate, caste certificate, family register by local administration, land allotment or house allotment certificate issued by the government, any document from before 1987 provided by post office, bank, Life Insurance Corporation or any local authority.

Many Matuas, many of whom migrated under adverse circumstances to India, don’t have the required documents. Their only option, most of those The Telegraph Online spoke to believe, is to apply for citizenship under the CAA.

However, Anjana Bala, 38, is scared that applying for citizenship would mean officially declaring themselves as Bangladeshi. She is scared that she and her family might be deported to Bangladesh or put in camps if they declare their original nationality.

She crossed into India illegally in 2004 to escape persecution in Bangladesh. She has Indian documents but doesn’t have voting rights yet. But her three children, who were born in India, do have voter’s ID cards.

Similarly Mamata Biswas, 70, is scared that if she applies for citizenship and has to declare her original identity, her 40-year-old daughter and 36-year-old son will also have to declare themselves as Bangladeshis, which might lead to them losing their jobs or her grandchildren being expelled from school.

Mamata has never voted in India; but her son and daughter have.

Another young man from the Matua community, who works in North 24 Parganas, was scared of losing his job because he hasn’t explicitly revealed his identity at his workplace.

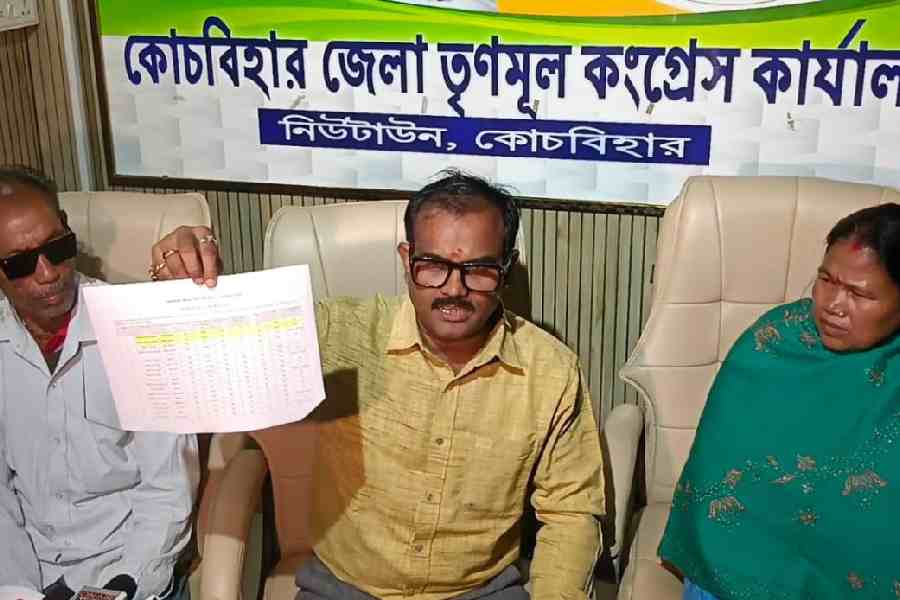

“The Matua community was used as a ladder to achieve power,” Md Salim of the CPM said at a public meeting earlier this week, accusing the BJP and the Trinamool of exploiting the community for electoral gains.

“Once their objectives were achieved, the community was abandoned,” Salim said.

The CPM, he said, would stand by the Matua community and others who had exercised their franchise for years but faced the threat of deletion after the SIR exercise.

Chief minister Mamata Banerjee has also vowed to protect the rights of the Matuas. It is believed that support from the Matuas has helped her rise.

The BJP has been fighting for years to increase its support base within the community, specially through the promise of citizenship.

Despite such assurances, the community has been left anxious with the SIR.

Most members of the Matua community The Telegraph Online spoke to said they were scared of being deported, put into concentration camps and all their documents becoming invalid.

Ask any Matua person about where their fears stem from, and they will tell you that “people have been talking about it”.

“The Matuas have a sway over 18 Assembly constituencies, out of which last time the BJP won 15,” said political analyst Suman Bhattacharya.

“This time around, because of the SIR, the BJP has shot itself in the foot. Many Matuas will lose voting rights, whether because of SIR or because of applying for citizenship under CAA. That, combined with the fears, will severely hurt the BJP’s prospects. And the TMC is going to reap the benefits of this.”