|

Thanks to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, we all know the Gulag. But that would hardly inspire us to retrace the long, arduous treks that prisoners of conscience would undertake till the Fifties, from Siberia to Calcutta, to escape the Stalinist regime.

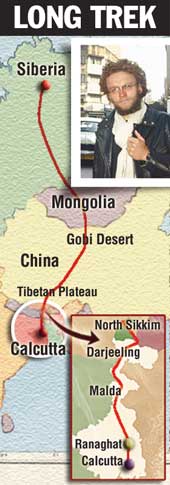

Sylvain Tesson, 31, a Paris-based travel writer, reached town three days ago after just such a journey on foot, on horseback and bicycle to follow in the footsteps of Slavomir Rawicz of Poland, who had fled the Gulag in 1941 and arrived in Calcutta a full year later. After that heroic walk, Rawicz, who is now 87 and lives in London, had written The Long Walk. Tesson read the book and decided he would do a Rawicz.

Tesson, who graduated as a geographer, prefers either to walk or take some other slow mode of transport that allows him to “know people”. He walked from Bhutan to Afghanistan in 1997, rode across central Asia in 1999, went on an archaeological mission to Afghanistan in 2001, and returned the next year to help open a school for girls. All his trips were funded by his publisher.

But he doesn’t go in for adventure for adventure’s sake. There has to be “a good story” behind it and “a difficult terrain” that would energise him. Tesson wanted to retrace Rawicz’s journey for it would give him the opportunity to probe the lives of those who gave Stalin the slip.

For him, it had the added attraction of being an interesting geographic trip from the Arctic to the tropics. He discovered how hundreds had defied death to win back freedom, and the only way to freedom was the south.

The great escape was re-enacted in 1937, when the USSR occupied Mongolia, and after 1950 when Maoist China annexed Tibet. Later, Tesson found out that in Calcutta, a Russian named Boris had rescued about 21 people in 1952.

Tesson embarked on his journey in mid-May 2003 from the ruins of an abandoned Gulag. In summer, the mercury soars to 45-50 degrees Celsius, and he walked for two months up to Mongolian Taiga. The only time he felt threatened was when he encountered black bears. “But they were not aggressive,” he recounts, blond hair and beard framing his face like a halo.

In his light bag, he carried a tent, sleeping bag, map, satellite compass, knife and dry food. He arrived at the Mongolian border in July-end, bought a horse he named Slavomir and rode from north to south. Across the Chinese border was the Gobi desert. Here, he rode a Chinese bicycle right over the Tibetan plateau. Then he walked 300 km up to Lhasa, where he arrived in November.

Tesson trudged from Lhasa to the Sikkim border but the Chinese army did not allow him to cross it. So, he had to take a detour of 2,000 km to reach the same point only one-and-a-half km across the Chinese border. A military permit allowed him to walk from North Sikkim up to Siliguri. From there, he cycled down to Ranaghat.

Tesson, who plans to ride back to Paris on his Royal Enfield, says he just does not have the wisdom to realise that “it is enough to stay where you are.”