|

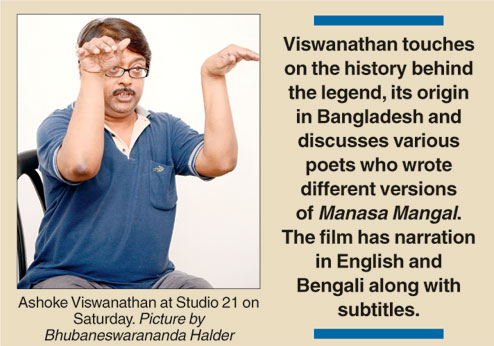

Is there historical basis behind the story of Manasa Mangal? Is the legend of the snake goddess a complex political text in disguise? Film-maker Ashoke Viswanathan explored these questions and more in his 30-minute docu-drama, The Legend of Manasa, screened at Studio 21 on Saturday.

The short film, produced by Central Institute of Indian Languages, deftly fuses narration, animation, enactment, patachitra, academic discourse and even live pala to narrate the legend of the goddess and the history behind the folklore gaining popularity.

“Manasa is the goddess of the Dalits and the subalterns. Her legend represents the rebellion of the weaker classes against the power-holders,” said professor Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay of Jadavpur University’s film studies department in the discussion that followed the screening.

The docu-drama starts with Viswanathan, dressed as a snake charmer, explaining who Manasa really is. The “non-Aryan snake goddess” had needed the patronage of a rich merchant like Chand Sadagar to make her presence felt in Bengal. But Chand refused to worship her even after the death of his seven sons. Finally Behula, the newly-wed wife of his youngest son Lakhindar (who dies of snakebite on his wedding day), travels to the gods with her dead husband’s body in a raft, wins Manasa’s forgiveness and manages to bring Chand’s seven dead sons back to life. In return, Chand becomes a devotee of Manasa, although he always prays to her with his left hand, the right being reserved for Lord Shiva.

Viswanathan touches on the history behind the legend, its origin in Bangladesh and discusses various poets —Kana Haridatta, Narayan Deb, Bijay Gupta, Bipradas Pipilai and others — who wrote different versions of Manasa Mangal. The film has narration in English and Bengali by the film-maker and his wife Madhumanti Maitra along with subtitles.

The plot hints at class conflict and the triumph of non-Aryans over Aryans. Behula epitomises an eternal love story and the best of Indian womanhood.

“Manasa Mangal is popular even as a political rhetoric. Manasa, however, is more popular in matriarchal societies. In north India, she is not that well known,” said Mukhopadhyay. He mentioned how Jibanananda Das had immortalised Behula through his poems.

Viswanathan said he wanted to test the historical veracity of the legend through his documentary. The shoot of the film spread over a year and a half and took him to various locations, including the rural areas of Jalpaiguri district, and Lakshmikantapur and Buriganga in South 24-Parganas.

“The legend is very complex. So many poets have written variations of the kavya. Chand may not want to worship Manasa initially but he has his good qualities. The epic has a Homeric tragedy feel to it at times,” Viswanathan said during the discussion after the screening.

The film-maker also narrated his experience of holding a Banded Krait during the shoot. “My wife and I could only hope that it would not bite us,” he said with a laugh.