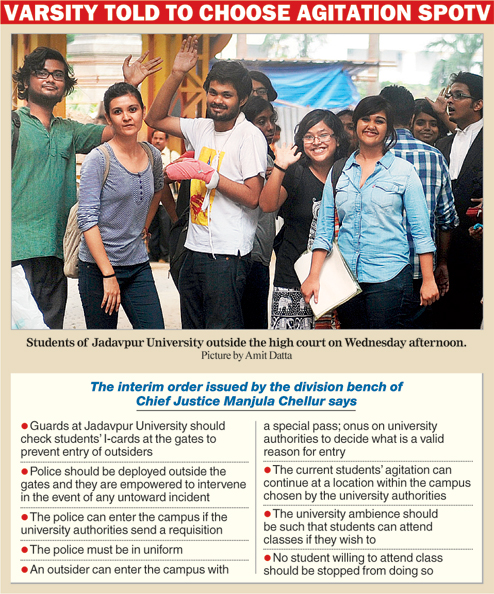

|

Calcutta High Court on Wednesday said students of Jadavpur University willing to attend classes should be allowed to do so while the rest could continue their campus agitation at a place designated by the university authorities.

The division bench of Chief Justice Manjula Chellur and Justice Asim Banerjee said the ambience of the university should be such that willing students weren’t prevented from attending classes by those involved in the agitation.

The observations were in response to a public interest litigation filed by a college teacher from Hooghly, seeking resumption of classes at JU.

Chief Justice Chellur and Justice Banerjee asked the authorities to make it mandatory for the private guards manning the university gates to check the I-cards of students before allowing entry. The bench had at first suggested that the police be asked to screen anyone visiting the campus but withdrew it after a lawyer representing the students said the move might escalate tension.

But the judges did ask the police to set up posts outside the university’s gates and deploy personnel in uniform to quell any law and order problem. The police are empowered to enter the campus if their services are requisitioned by the university, they iterated.

“It would be just and proper to bring the university to normality. Therefore, we are of the opinion that there has to be minimum interim directions, which will assist the university in its day-to-day functioning,” Chief Justice Chellur said.

Both judges maintained through the hearing that restoring normality was their main objective. “I have heard that the chancellor has appealed to the students to go back to classes. I have also read in the papers that the (interim) vice-chancellor is willing to talk to the students,” Chief Justice Chellur said.

When Arunava Ghosh, one of the lawyers appearing for the students, displayed a suitcase containing a sheaf of papers that he said included the signatures of 3,000 students who wished to boycott classes, Justice Banerjee asked him whether he knew what the rest wanted. “I am told there are 11,000 students in the university. You have signatures of 3,000. What about the remaining 8,000?”

Officials at JU, which plunged into chaos in the wake of the alleged police action on the campus last week, said the court’s order would help them do just what was required to restore normality. “We had sought police posts at the gates after 8pm. The court has ordered round-the-clock police deployment, which is better than what we had asked for,” an official said.

Around 10 students were present in the courtroom when the petition was being heard. Also present was the man whose ouster they have been demanding: interim vice-chancellor Abhijit Chakrabarti. He entered the court around 1.50pm, 10 minutes before the hearing resumed post-lunch.

During the 55-minute hearing, lawyers Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharyya and Ghosh repeatedly interrupted the bench to put across a point on behalf of the students. At one point, Chief Justice Chellur said: “There is division among the students.”

Bhattacharyya sprang to their defence. “How do you know? What is the evidence? All the 11,000 students are united and they do not want to attend classes,” he said.

Bhattacharyya said there was no campus in the world that had ever barred students from protesting against anything they didn’t agree to. “This order will put the court to shame,” the lawyer told the chief justice, who was initially inclined to issue an order barring the campus agitation.

The bench relented after Bhattacharyya’s argument and said the students could continue their agitation at a place on the campus chosen by the university authorities.

After several interruptions, the chief justice said: “You may not agree with me. You may move against the order.”

There was a heated exchange between the rival lawyers too. Bhattacharyya said the PIL smacked of a political motive. The petitioner’s lawyer retorted: “That is why two political persons, Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharyya (CPM leader) and Arunava Ghosh (Congress) are defending the students.”

Bhattacharyya and Ghosh mentioned two instances in support of their argument that student politics was “the culture of West Bengal”.

“(Rabindranath) Tagore had once stopped the police from entering Santiniketan,” Bhattacharyya said.

Ghosh spoke about an incident dating back to 1969 when “classes at Presidency College were shut for six months”.

A JU professor who is well read on Tagore said: “We were then a colony. The police had suspected Tagore of harbouring some members of the Anushilan Samiti, which the British considered a terrorist organisation. The police were planning to enter the campus but Tagore stopped them.”

Then in 1969, seven or eight students of Hindu Hostel were expelled for supporting Naxalite activity, triggering a protest that brought the police.

“It is sad that an example from the Naxalite movement had to be used to explain the problem at JU,” said the professor, an alumnus of the erstwhile Presidency College.