|

A for Abar Khabo: In an online tribute, a non-resident Bengali has gone to the extent of thanking his father-in-law for having a house near Bhim Chandra Nag’s famous old proud-to-be-shabby sweet shop in Bowbazar that boasts of a Cooke and Kelvey clock with Bengali numerals. For the son-in-law on his visits to Calcutta, staying with his in-laws is like living close to the garden of earthly delights, where the foremost pleasure is Abar Khabo, the most exquisite of sandeshes.

It is a delicate thing. It is sandesh outside, but of the soft kind (norom pak), and inside is the softest kheer and pistachio.

Abar Khabo, meaning “I want to have it again”, cannot be exported, says Bhim Chandra Nag, though kora paak (hard sandesh) can be.

B for Boroline: The little green tube of near-mythical properties attributed to it by generations of Bengalis since it was launched in 1929 by GD Pharmaceuticals. An ointment made with the antiseptic boric acid, the astringent and sunscreen zinc oxide, and the emollient lanolin, meant to be used on cuts, cracked lips, rough skin and to treat infections, it has far transcended its original purpose. Its powers are said to cure everything, from matha dhora (headache) to heartbreak. It has evolved in one way: the thick, white cream that resists being rubbed in is now available in small jars as well as the little green tube, and unlike Abar Khabo, it is carried away in bagfuls by non-resident Bengalis.

High time Boroline was applied on the state’s economy.

B for Biscoot: Bengali for biscuit. Had with tea or just, any number of times a day, “biscoot” is a Bengali habit. So much so that a character in Sukumar Ray’s Ha Ja Ba Ra La claims: “Na, na, amar shoshurer naam Biscoot (No, no, my father-in-law’s name is Biscoot).”

B for Bangla bands: Bengali for cool.

C for Cadaverous: Meaning “like a cadaver”, corpse-like, ghostly in the original English (think stories by Edgar Allan Poe), in Bengali it can mean anything horrible. You can have a cadaverous neighbour; a traffic jam can be cadaverous. You may have a cadaverous fall from a bus and live to tell.

|

C for Chaap: Pressure, but the word has an extra edge. Bengalis are particularly wary of applying it on another and more wary of it being applied on them. “No chaap” is the philosophy of “I don’t push you, you don’t push me”. Life should be gentle.

D for Daak naam: Punjabis have it too, but Bengalis win the race for embarrassing nicknames hands down. Imagine a middle-aged man on a dating site — there are many of them around — having to admit to a name like Babai. Or Paplu.

E for Ei Poth Jodi Na Shesh Hoi: Bengali mating call.

E for Ei je shunchho: Equivalent for “darling” for married couples of a certain vintage.

F for Feluda: Tall, handsome, single, chaste, whose brain is his weapon (magajastra). Only on the rarest occasion does he use his .32 Colt revolver. Feluda is not only Bengal’s favourite detective, he is also Bengal’s last great action hero. His charm unites generations, though many from GeNext, alas, may be only familiar with him through English translations of Satyajit Ray’s originals or films.

G for Gelusil: What Moby Dick is to Captain Ahab, Hobbes is to Calvin, acidity is to the Bengali. Gelusil, the little pale pink tablet, kills ombol, restores hope.

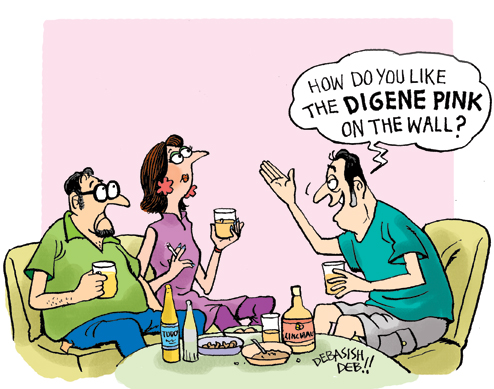

Its close cousin Digene, which also comes in a pale pink shade, is relied on almost as much. Proof: Digene Pink is the name of a shade used to paint interiors in rural Bengal.

|

H for Horlicks: Responsible for the growth of Bengali middle class.

H for Harmonium: Originally the pump organ, another name for the harmonium, was a reed organ that came with foot-pumped bellows. It came into India with missionaries in the 19th century and evolved beyond recognition, especially in Calcutta. The hand-held harmonium was designed in response to local requirements, since Indian musicians prefer to sit when they sing or play an instrument.

Harmonium is used in many parts of India, but nowhere more than in Bengal, where a training in music, and therefore childhood, was always accompanied by the instrument till a few years back. The young girl practising at the harmonium in the evening was as central to middle-class Bengali culture then as Bangla bands are now.

H for Hebby: Bengali for awesome.

I for Ilish: National fish of Bengal. No one except a Bengali will understand the passion it excites. Despite the kanta. The faithful will say because of the kanta.

I for Indrajaal: P.C. Sorcar, Senior and Junior, famous Indian magicians, have enchanted Bengalis for decades.

I for Iye: Iye can mean anything when the speaker is at a loss for words. His audience is supposed to figure out what he means.

Example: “Iye mane iye kore iye jaben? (I mean iye after iye will you go to iye?)”

|

J for Joaner Arok: Another product said to have near-mythical properties. Aqua Ptychotis, a spelling a Bengali child was brought up on, along with pneumonia, is a joan-based pungent brew manufactured by Bengal Chemicals. It cuts through all the oil of a Bengali wedding feast and allows digestion. If it was available abroad, Jeeves would have served this to Bertie the morning after.

Did Bengalis always eat so much?

J for Jibonmukhi gaan: Bengali angst.

J for Jibone Ki Pabo Na: In which number Soumitra Chattopadhyay does a twist in the film Teen Bhubaner Paare. Bangali Retro Cool.

K for Kobiraji: Well-known history, but worth repeating. This batter-fried cutlet derives its name from “coverage”, is had in the evenings and is chased by Joaner Arok and Gelusil.

L for Lebu cha: Another pungent liquid, arrived at after sprinkling bit noon on sweetened tea liquor. Good for the stomach, bad for delicate nostrils.

L for Lyad: The position on the bed or the sofa perfected by Bengalis, especially after a heavy meal, when the TV is switched on and the mind is switched off, except for the contemplation of the next meal.

L for Lalmohanbabu: Feluda’s unsuspecting sidekick. Pure delight.

M for Moshari: The mosquito net, which the Bengali, even in AC homes, reveres, and ties and unties, till death do them part.

M for Mohendra Lal Dutt: Most revered maker of the chhata (umbrella), a very important Bengali accessory. Non-resident Bengalis vouch for this brand too.

N for Nyaka: Though reams have been written on the word, this has to be said again.

Nyaka is that special word that cannot be translated. It is like “toska” in Russian — Vladimir Nabokov: “No single word in English renders all the shades of toska. At its deepest and most painful, it is a sensation of great spiritual anguish, often without any specific cause. At less morbid levels it is a dull ache of the soul, a longing with nothing to long for, a sick pining, a vague restlessness, mental throes, yearning. In particular cases it may be the desire for somebody or something specific, nostalgia, love-sickness. At the lowest level it grades into ennui, boredom.” Or like the Czech “litost”: the closest definition would be a state of agony and torment created by the sudden sight of one’s own misery. Or the German “schadenfreude” — the feeling of pleasure derived by seeing another’s misfortune.

“Nyaka” cannot be rendered into any other language. The closest would be a delicateness of manner that is annoying. Applicable to all genders.

N for Nonsense: Derived from the same English word, in Bengali it is an invective or it can be used to describe a person in a damaging way. Examples: “You are a nonsense!” Or, “He is a nonsense!”

O for Ol kochu bhatey: A delicacy, meaning boiled and ground Ol Kochu, a wicked yam, which always makes the throat of the quarrelsome go itchy.

Ingredients:

250 gm Ol Kochu

1 tsp ground mustard seeds

3 chopped green chillies

2 tbsp mustard oil

Salt to taste

Method:

Peel and cut the Ol Kochu into small pieces. In a vessel boil it with salt till it is cooked well. Remove from heat and drain the water. Mash the Ol Kochu with chillies, ground mustard seeds and oil and serve with hot, steamed rice. Yam yam!

P for Paanch phoron: Maithili, Odiya and Assamese cuisines use it too, but paanch phoron, the all-spice made of five spices, must be mentioned in the context of Bengalis. The five spices are: methi (fenugreek seeds), kalo jeere (nigella seeds), jeere (cumin seeds), shorshe (black mustard seeds) and mouri (fennel seeds). Sometimes instead of mustard seeds, Bengalis use randhuni.

P for Phuchka: It is not Golgappa, it is not Paani Puri. Sharp, round, hard-hitting, Calcutta’s phuchkas are the world’s best.

Q for Queue: Calcuttans have a special talent for queuing up. If a Calcuttan sees a queue anywhere, he is likely to join it, then ask what it is for. Then he is likely to jump it. Even if it is to get into a lift.

R for Rabindranath, Rabindrasangeet: Self-explanatory.

R for Roshogolla: What attracts Bollywood to Bengal, other than mishti doi and the second Hooghly bridge.

R for Rokke rokke: A call to halt anything that moves, including an aeroplane. Legend has it that a reputable professor of social history got into the wrong flight at the Calcutta airport. He got out and ran towards the right flight, crying: “Rokke rokke!”

S for Satyajit, Suchitra, Sourav: The greats of Bengal. Don’t forget that the latest Nobel Prize winner from Bengal is Sen, Amartya.

T for Totto: The sets of gifts that the families of the bride and groom exchange with each other, decorated on wooden trays. It is a mini industry.

T for Tumi je amar, ogo tumi je amar: Bengali mating call.

U for Uttam Kumar: The greatest Bengali superstar towers over Tollywood still. He would have been the last word, if not for...

V for Vote: The biggest parbon. Also known as vote pujo.