|

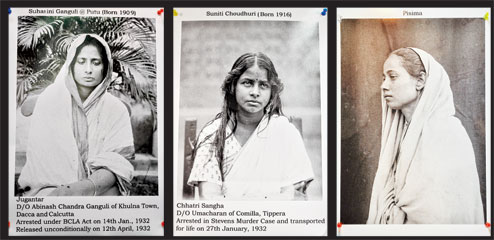

| Photographs of Suhasini Ganguli, Suniti Choudhuri and ‘Pisima’ at an exhibition on women revolutionaries of Bengal organised by the directorate of state archives. Pictures by Arnab Mondal |

A young woman, who looks slightly older than her 16 years, her hair gathered in a knot at the nape, in a white cotton sari, looks ahead of her in a profile shot. She looks calm, with a soft expression in her eyes. She is Santi Ghosh, alias Ila Sen, from Comilla, “secretary of Chhatri Sangha”, who was convicted under the Indian Penal Code and Arms Act and sentenced to transportation for life on January 27, 1932, for killing the district magistrate of Comilla.

Next to her is the photograph of her friend, the 15-year-old Suniti Choudhuri, alias Meera Devi of Chhatri Sangh, “custodian of firearms”, who was in charge of training female members in lathi, sword and dagger play. She too was convicted and sentenced to transportation for life with Santi for the same murder. She looks straight at the viewer, her face determined, her hair parted in the middle and hanging loose, framing her attractive face.

In 1931, the schoolgirls, in retaliation for Bhagat Singh’s death, approached the magistrate apparently to ask permission for a swimming pool and shot him. Despite the sentence, they were not transported, but sent to Alipore Central Jail, where they stayed till they were freed in about a decade.

Their photographs from the Intelligence Bureau (IB) records kept by the British and the details about the conviction and jail terms of the two girls are part of an exhibition called ‘Women Revolutionaries of Bengal’, which has been organised by the directorate of state archives at their office on Theatre Road. Put up initially for the archives week celebration from March 4 to March 10, the exhibition will stay in place for a year, though with fewer lights.

Santi and Suniti are two of the 118 women whose faces line the walls of the archives, brightly-lit now. But they are among the more well-known, along with Pritilata Wadder, Kalpana Datta and Bina Das.

The rest, too, were involved seriously enough in the struggle for India’s freedom — often with armed groups like Jugantar and Anushilan Samiti — to have found a place in the intelligence records or behind bars.

But at the exhibition they are just rows of arresting faces, mostly young, with an intense and resolute expression, a significant number of them wearing round glasses, plain white saris, the married presumably are the ones with the anchal covering their heads. Though she could be a widow posing as a married woman, with sindur, as did Suhasini Ganguli. Many of them had aliases. Many were trained in firearms.

The archives department had received 42,000 glass slides from the IB, which they have been processing, preserving, digitising and printing painstakingly, as in the case of the photographs of these women. The photographs matched the files from the department.

Not much else is known by the department. Who were they? Who was Mrs Umar, an exotic-looking woman? Who was Foo-Pu, her Oriental features marking her out from the rest? Who was “Pisima”, a young woman with a striking profile?

The state archives department also wants to know. They are inviting people to visit and identify these women for their records.

But the department makes some observations in general. The women were mainly from the three upper castes of the Hindu society and in many cases, they had the support of their families.

Many of the photographs have a feature in common: the same palm fronds appear as the backdrop. The women were photographed in the same spot, near a few steps. One wonders which building it was — the archives department couldn’t tell — and what the palm fronds were doing in IB pictures. A touch of the aesthetic?

MAD meet

|

| A painting at the MAD summit 2013 |

To observe International Women’s Day, Anjali, a city organisation that works with people with mental health problems, held MAD Summit 2013, on March 5, an event that celebrated the recovery of several men and women. They participated in several workshops, joyously, painting, singing, dancing, writing the stories of their lives at the venue, Seva Kendra in Entally.

Several demands were raised for recovered patients. “After rehabilitation, the government should create economic opportunity, especially for women,” said Ratnaboli Ray, who heads Anjali. “There should be enough people to care for them. Medicines should be accessible and affordable, particularly in the rural areas. And recovered patients should be discharged speedily,” she added.

The event led to that fundamental question again, who is “normal” and who is not. As if in answer, something happened at the end of the day, recounts an Anjali employee. Of the recovered patients and their families, someone said most of them looked “normal”, but a few did not. “There was a woman, with short hair, wearing a bright coloured saree, and a bright yellow flower in her hair, she does not look well... recovered... normal!”

He apologised profusely when he came know he was referring to Ratnaboli, the head of Anjali.

Bengali play in Hindi

Twenty-five years after it was written, Manoj Mitra’s popular play Alokanandar Putrakanya will be performed in Hindi as Alka by Little Thespian at the ICCR Satyajit Ray Auditorium on March 12.

“The play deals with women as mothers, daughters, wives, neighbours… their emotions and relationships with each other as well as society,” said Uma Jhunjhunwala, the president of the group and the director of the play, during a special preview at Gyan Manch. Uma plays Alka in the play that will start at 6.30pm on Tuesday.

(Contributed by Chandrima S. Bhattacharya and Sebanti Sarkar)