Tall and hefty Kabuliwalas or men from Afghanistan in their voluminous salwars and kameez, embroidered waistcoats and huge turbans with fantails were once a common sight in Calcutta. They lent money to local people and sold asafoetida and dry fruits tied in a large bundle as they roamed the streets.

The Kabuliwala in Rabindranath Tagore's short story of the same name written in 1892 used to offer dry fruits to the little Bengali girl named Mini who reminded him of his daughter back home. Ranen Ayan Dutt's poster for Tapan Sinha's adaptation of the Tagore short story shows the protagonist carrying his wares on his back, dwarfing the tiny Mini.

This short story was the starting point of a project taken up jointly by Moska Najib and Nazes Afroz, two journalists formerly with the BBC who also take photographs, to document the lives of Kabulis in Calcutta, many of whose forefathers settled down here when they first arrived 170 years ago.

Moska Najib is originally from Afghanistan but has been an Indian resident for a long time ever since her family was forced to leave their troubled homeland. Nazes Afroz began his career as a journalist in this city. Their project has resulted in the exhibition of photographs titled From Kabul to Kolkata: Of Belonging, Memories and Identity now on at The Harrington Street Arts Centre. It was supported by the Goethe-Institut Max Mueller Bhavan and India-Afghanistan Foundation. The exhibition has already travelled thorough Kabul, Delhi and Dhaka.

at The Harrington Street Arts Centre

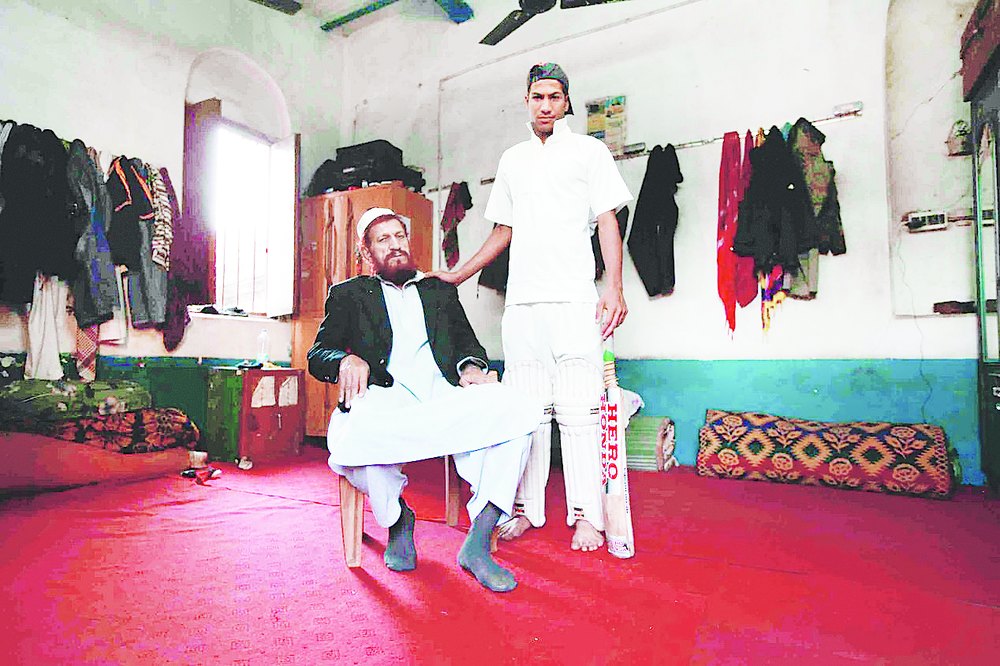

The matter-of-fact photographs explore how the Kabulis adapted themselves to this foreign land, where they were in a minority. But even when they did not return for generations and married local women (mostly in purdah), they still dreamed of their homeland. The two photographers discovered the Kabulis all over Calcutta and the suburbs. The exhibition begins with a series of portraits of these men who are very much at home here, but are still protective of their identity. They still converse in Pashtu, have their meals at their exclusive eateries, and perform their Id dance in the Maidan every year. The photographs of communal dancing are in black and white.

In one photograph an elderly Noor Khan stands in a room in Cossipore which his grandfather had rented 150 years ago. On one trunk is painted his name, and the one beneath it, which is painted with flowers, belonged to his grandfather. In another series, the Kabulis break fast during Ramadan, and in one telling frame are the remains of a feast - a giant bone and scraps of rotis. The young offspring of early settlers gather for adda on their motorbikes at a street corner. They move around the city on rickshaws or in taxis.

In one panoramic frame, an Afghan makes a call on his mobile in the Maidan with the Victoria Memorial Hall towering before him. A close-up of a money-lending licence says the man was a resident of "Pakhtunistan", a state which does not exist in reality but which all Kabulis referred to as their home earlier.

Today, Kabulis deal in semi-precious stones and run tailoring shops in Burrabazar. But as one photograph demonstrates, although they are equipped with ration cards and all other evidence of their identity, many still don't have passports. Yet, when they die they are buried at the Gobra burial ground. But, as Nazes Afroz points out, Kabulis are not outsiders any longer. They share meals with Bengali friends, and although it was set up, one shot shows a turbaned Kabuli at a wedding reception with the bride in the background. The catalogue includes a translation of the Tagore short story by Sister Nivedita.