|

|

|

| Extraordinary experience: (From top) Anne Wroe and her husband, Malcolm, in conversation with pianist Sourendra Mullick at the Marble Palace; on a north Calcutta street; at the Sovabazar Rajbari. (Sudeshna Banerjee) |

About a week into my stay in Calcutta, I realised I had written nothing down. No quick descriptions, no musings or poetic snatches. This was unprecedented for me; as a writer, I scribble all the time. But I reasoned that when you are in the midst of an extraordinary experience, like swimming in the midst of a turbulent sea, you don’t record it; like a piece of bobbing flotsam, you go with the flow.

In any case, for a foreigner, it is the first experience of India that administers the shock: the smell of jasmine and urine in the night streets; the sheer numbers of people pushing through the markets and hanging off the trains; the head-borne loads of firewood, rags, cauliflower, cooking oil in cans; maimed stumps knocking at the window of the car, and beggars clawing at your clothes; the terrific teeming squalor of the towns, underneath beaming banners for wedding finery and mobile phones.

But since this was not my first journey to India, all that I already expected and took for granted. The experience of Calcutta was something else.

If Delhi is male, a proud, officious army colonel striding across a Lutyens parade ground, Calcutta is female: a vast, organic, chaotic Mother, embracing to her ample breast everyone who visits her. She has a woman’s carelessness, so that her streets seem to take off in one direction and swerve round into another, or founder in alleyways so narrow that two men with carts make an impasse.

She is a slattern, throwing into huge heaps plastic bottles, green plundered coconuts, broken bricks, human waste, white egg-shells and clay teacups; she never sweeps, but lets the dust pile up by kerbs and walls, coat the leaves of the magnolias, clog up the spokes and gears of bicycles and sift through the humid galleries of the Marble Palace, veiling thickly each damp-dark painting and marble Venus, each rust-meshed birdcage and glass globe.

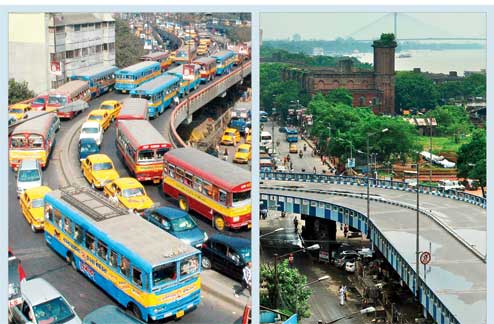

To walk in her streets for long — or to try to walk, sharing her potholed roads with manic yellow cabs, battered buses, stray dogs and human rickshaws — is to acquire black feet, dirt under the fingernails and a dry cough in the throat that only sweet, thick chai will cure. Yet it is the same dust that flatters the city at twilight (“cow-dust time”) and in the hour of dawn, misting in pink the dome of the Victoria Memorial and the prospects along Indira Gandhi Sarani and Eden Gardens road. Under the burning red globe of the unclouded February sun, Kali’s colour, the city softens, blushes and spreads herself as the traffic, her life-blood, pours through.

Fundamentally it is Nature, not the city, that nourishes us. But Calcutta also includes in her Protean character a green, nurturing side. Trees, flowers and lawns line the principal roads. (“A clean city has clean garden” read the municipality’s small, neat signs, hope triumphing over experience.) On the Maidan, the great open space that fills the heart of the city, flocks of sheep and goats graze the worn grass. Vagrants sleep there too, rolled in their ragged blankets and with their stick-limbs baked by the sun; sports clubs come to play cricket, everyone in impeccable whites; but this is essentially a rural scene, with shepherds leaning on their staffs and their animals seeking the shade.

On the city outskirts, too, the traffic jams begin beside fields where peasants are cutting cauliflower. At dusk the rat-like house crows descend in a raucous, tattered mob into the trees off Park Street; at dawn the sparrows sing there; at 2am the city lies in a profound, improbable village silence, broken only by the howling, scrapping conversation of wild dogs.

Perhaps, I thought, it was this rural aspect that made me feel such fondness for the city — despite the poverty, the filth, the feral children and human beasts of burden, the reeking trail of goat-blood in Kalighat, and everything else that she could throw at me. But other reasons soon emerged.

WONDER OF WORDS & WATER

The first was words. Calcutta is a place in love with them, perhaps more so than any other city in the world: from Rabindranath’s quotations at bus stops, to his songs playing at traffic lights, to the novels and poetry displayed in plastic wraps on the pavement outside the Oberoi Grand, to the teetering piles of literary paperbacks lined up along College Street, their lower strata so mildewed and compacted that they must now be part of the fabric of the city, her mud and dust. In Calcutta I dined in rooms lined with books, climbed stairs stacked high with them and explored Borgesian libraries where each room led into a further chamber of leather-bound delight.

There are few shops so humble that they do not have a bench or two outside for the serious scanning of a newspaper or some impromptu adda, wandering over every subject from the transcendent to the mundane. On every side something prompts me to think of poets: even the conductors leaning from the buses, flourishing sheaves of tickets to show they are turning left, remind me that Jibanananda Das, his mind full of paddy-field birdsong and stars, was run over here as he tried to cross the road.

After words comes water. I need the sea, or rivers, to write by, as many authors do; the flow of water mimics the flow of thought, continuously moving and reshaping. In Calcutta the great Hooghly/Ganga is often out of sight, with modern skyscrapers and apartment blocks springing up to obscure the views once enjoyed by the older buildings, through trees to water. Yet cities built on rivers never lose sight of them entirely. Presumably it is still Ganges water that gushes from public pumps all over the city for the wildly enthusiastic soakings and soapings of half-naked men and boys (and once, on a corner near Shyambazar, for the tender shampooing of a small black dog). River light shouts into the sky, as it does here, and when that light is holy it is all the brighter; so that it is easy to believe that it was from the balcony of a now-vanished house in Sudder Street that Rabindranath saw the world blazing with radiance, and each human passer-by aflame and dancing “like waves on the sea of the universe”.

Birth, dissolution and rebirth are the business of rivers. But where the Thames and the Rhine hide this essential work, Calcutta celebrates it. Wandering down to Judges’ Ghat on the Monday after Saraswati Puja we found the goddess of learning, in dozens of painted and garlanded plaster effigies, being lowered into the silty river and floating away, until only her praying hands appeared above the surface. Businessmen and lawyers, babus and women wearing sparkly sandals in the thick, grey mud, paid homage to her as they surrendered her to the water. At Kumartuli some days later we saw her rebirth, as the Ganges mud in which she had dissolved was smeared over forms of woven straw to be plastered and painted again. What might be called a philosophy of decay and revival animates the whole city. This, too, endeared it to me.

GRAVE NUMBER 1022

But the deepest sense of a connection with the mother-city came as a surprise. It occurred in Park Street cemetery, where among the mouldering Moghul-style tombs and the overhanging palm and jackfruit trees an ancestor of ours, perhaps, lies buried. We had no idea Elizabeth Wroe was there until we found her name, by chance, on the caretaker’s list; no one from my family or my husband’s was known to have gone to India. But she came, and in 1780 died here, at the age of 28.

Her grave, number 1022, has vanished now, together with 20 others that were cleared some years ago by a nurseryman from Orissa who wanted to sell flowers there. He built a hut (of brick, roofed roughly with black plastic and a blue tarpaulin) at the base of an immense mango tree. The mangoes are very small, the caretaker tells us, but sugar-sweet.

His sons run the place now. One watches us as we scrabble about in the undergrowth, a man of about 30 in a check shirt, with watering-can in hand. The open-fronted hut contains only a bench, with newspapers folded on it, a cloth hammock and a chair with a rack under the seat, on which lies someone’s blue comb. Various potted plants stand about, and on the mango tree hangs a picture of Radha-Krishna in a silver frame, with a plastic bowl below for offerings.

Somewhere here, under the hard earth, Elizabeth’s dust lies. Around her Calcutta, vast, horn-blasting, crow-calling, dirt-whirling, flows tumultuously on.

Ann Wroe, the Obituaries Editor of The Economist, is the author of six books, most recently Orpheus: The Song of Life. She was in Calcutta to speak at the annual conference of the Centre for Studies in Romantic Literature