|

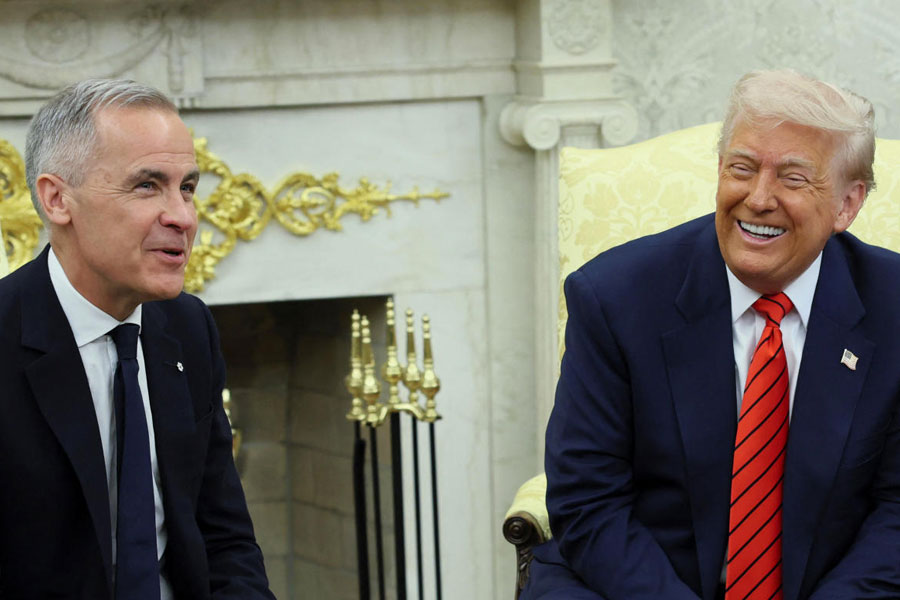

| Shree Bose with her Google Global Science Fair trophies and (below) her mentor Alakananda Basu |

|

Ovarian cancer research has found a champion Bose and Basu team with a little help from a blue spinach.

Shree Bose, a 17-year-old student of Fort Worth Country Day School in Texas, has found a way to boost the efficacy of the chemotherapy drug Cisplatin at a stage when cancerous cells begin to resist it. The feat won Shree, the daughter of emigrant parents, the grand prize at The Google Global Science Fair.

But bigger than all the material rewards put together — a $50,000 study scholarship, a 10-day trip to the Galapagos Islands and a visit to the CERN particle physics laboratory in Switzerland — is Shree’s satisfaction at having made a difference to the fight against cancer.

Her mentor in the research project was Alakananda Basu, a professor in the department of molecular biology and immunology at the University of North Texas Health Science Center and a graduate adviser in cancer biology.

For Sree, it all began with an artificially pigmented blue spinach. The teenager, then a first grader, was asked “to come up with an idea that no one had ever thought of before” and the child in her thought of all those children across the world who have a problem with vegetables on their plate.

“My idea was that if we turned them a different colour, then they would eat healthy foods. So I decided that I would stain spinach plants by injecting them with blue food colouring, but forgot to water them. And I walked into the science competition with a dead, withered, stained spinach plant.... but after that I decided science was cool enough to stick with,” Shree recounted in an email to Metro.

Her next phase of ingenuity started when Shree was eight. She took apart a remote-controlled car to create a garbage can that would park itself on the kerb at the touch of a button from far.

Father Animesh Bose, a materials engineer with a degree from IIT Kharagpur, and mother Prarthana were as bemused as they were proud of their daughter’s invention. “She had grumbled about it, saying why can’t someone come up with a garbage-can system that can be remotely operated. We laughed it off. The next thing we know, she was taking apart the remote-controlled car,” Shree’s father recalled.

Her knack for invention flowered even as Shree expanded her interests, balancing swimming with playing the flute and the piano and, now, editing her school paper.

In 2009, she approached Alakananda to express her interest in medical research. The professor marked out Shree as a “highly motivated” student and assigned her a breast-cancer project that fetched her quite a few awards.

Alakananda later selected Shree for the Cisplatin drug-resistance project in collaboration with graduate student Savitha Sridharan. “She can pick up concepts and techniques very quickly.... as a high school student, she would perform more at the level of a graduate student. She not only has intelligence and motivation; she also has a very pleasing personality,” Alakananda said in an email.

Shree credits elder brother Pinaki, who she describes as “one of the smartest people I know”, and father Animesh with nurturing her talent.

The inspiration for cancer research came from personal tragedy. “Both my grandfathers passed away from cancer.... Seeing my family go through that just made me wish I could make a difference,” she wrote.

And what role has Calcutta played in the Bose and Basu success story?

Alakananda is from Asansol, but her academic base was this city. She graduated with chemistry honours from Lady Brabourne and did her MSc in biochemistry from Calcutta University. For her 17-year-old ward, the best memories of Bengal are not of holidays in Calcutta, but those of “swimming in the river in Ichhapur”, mother Prarthana’s hometown.