|

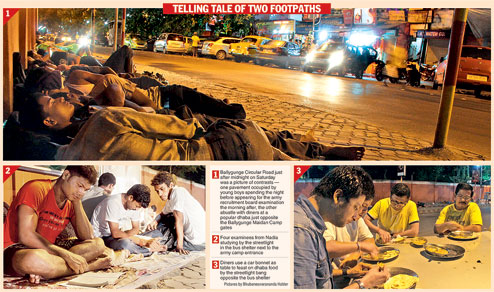

Alamgir Sheikh is immersed in his general knowledge book under the faint light of the trident lamps lining a Ballygunge Circular Road footpath, his study table-cum-bed for the night after a dinner of puffed rice and jaggery.

The other side of the 20ft strip of road is better illuminated, the headlamps of a sedan that has just screeched to a halt adding to the brightness of the lights at the popular Sharma Dhaba.

Akash (name changed on request), the young man at the wheel, gets off the car along with five friends to walk into the eatery that is still buzzing at 12.30am. They are there to “grab some grub” before heading to a rooftop party.

Alamgir, at 21 the same age as Akash, raises his head every time he loses concentration because of a car either stopping by the eatery or leaving. Dawn will bring to him the opportunity of a lifetime, and he knows he can’t afford to be distracted.

“I am from a village in Diamond Harbour and have come here for an army recruitment exam at this centre,” he says, pointing to the massive gates of the Ballygunge Maidan Camp a few feet away.

There are three more boys with him, all candidates for jobs in the armed forces.

Alamgir aspires to be a tailor, a job that could fetch him a monthly salary of around Rs 15,000, several times more than anyone in his family has ever earned in four weeks but less than what Akash sometimes spends to unwind on a weekend.

“Who are these people coming here in the middle of the night to eat?” Alamgir wants to know, as yet another noisy group enters the eatery across the street.

A similar question is preying on Akash’s mind in between morsels of dhaba food. “Who are these boys studying on the footpath?” he will ask Metro a few minutes later.

In the coincidence of Alamgir and Akash’s presence on either side of a Calcutta street on a Saturday night lies a story of the dichotomies of our times.

Both young men were born the year Manmohan Singh first took charge of a closed Indian economy and started the process of liberalisation that triggered what the world calls the “India growth story”. Two decades later, the 20ft strip of road separating their footpaths and priorities mirrors the great Alamgir-Akash divide.

“Our family income from farming has been dipping each year. I need this job because I have to take care of my parents and two elder sisters. I am trying to brush up on my GK. I have to crack this exam,” says Alamgir.

Alamgir is doing his BA in physical education at the Calcutta University-affiliated Fakir Chand College in Diamond Harbour. If he gets the army job — he has already tried getting into the CISF and West Bengal Police — the 21-year-old will have no hesitation in quitting college.

“I don’t know how long it will be possible for me to continue studying. My family’s well-being depends on me,” he says.

Mafijjul Haque Lashkar, Maidul Mandal Pal and Rafikul, the three boys sharing Alamgir’s footpath and general-knowledge book, aren’t any better off.

Maidul, from Shantipur in Nadia district, had done a 1,600-metre endurance sprint in less than six minutes as part of the physical screening test in April. Like the rest, his prospects of getting the job now depend on how he fares in the written exam.

The results of the test will be declared on August 10, and Alamgir and the other boys get goosebumps just thinking about it.

“An army job will spare us the everyday struggle to earn a meal. At least we won’t have to spend a night on a footpath preparing for an exam the next morning while people of our age are enjoying a meal on the other side that probably costs more than what we can earn in a month,” says Maidul, who has come with a plastic sheet for protection from rain (it did rain later in the night).

Recent data show that inequality in earnings has doubled in India over the last two decades, making it the worst performer on this count among all emerging economies. The country’s Gini coefficient, the official measure of income inequality, has risen from 0.32 to 0.38, 0 being the ideal score.

Reports say that consumption by the top 20 per cent of households grew at almost 3 per cent annually since the year 2000, against 2 per cent in the 1990s. But growth in consumption by the bottom 20 per cent of households remained unchanged at 1 per cent.

These are not just statistics, they tell in numbers what this description of the Saturday night scene on two footpaths of Ballygunge Circular Road attempts to say in words.

Akash, who has just learnt that the boys on the other footpath have come for an army recruitment test, isn’t curious anymore. “Oh! Is it?” he says, walking back towards his car.

The rooftop party awaits Akash’s arrival, he must rush now. Across the road, Alamgir awaits a new dawn.

Do you think Alamgir and Akash will always be on opposite footpaths? Tell ttmetro@abpmail.com