|

What was Bengal like in 1945? After the famine of 1943 and the Quit India Movement, was Bengal seething with patriotic anger or was life still moving at a peaceful pace in the countryside? Was there widespread antagonism to all things foreign or were rural children as well as adults ready to pose for a camera-wielding American?

Well, at least one white-skinned photographer managed to develop a rapport with Bengal villagers in 1945.

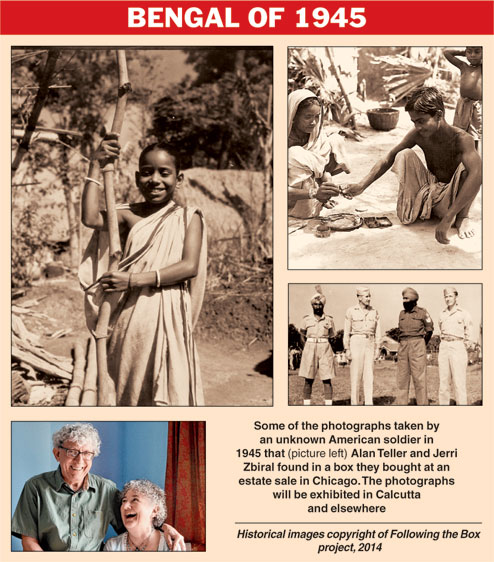

Children look at him with amused curiosity, sit on his camera case or laugh cheerfully as they share his chewing gum. There are village ladies with white conch-shell bangles and men who stop to smile as they work in fields, thresh paddy, build thatched huts, iron clothes or just sit chatting.

No one knows who this photographer was but a box containing 130 of his photographs — each 4inch by 5inch — and old, high-quality negatives in individual envelopes turned up at an estate sale in Chicago, where they were spotted by photographer and artist couple, Alan Teller and Jerri Zbiral. All that was known about the origin of the box was that its last owner had picked it from a junk sale somewhere in the US. Alan and Jerri bought the box for $20.

Jerri and Alan will be in India till April, courtesy Alan’s 2013 Fulbright-Nehru senior scholar award for research into the source of the box and the perspectives they offer, past and present. They have been visiting locations, talking to scholars and exploring archives to create new art works based on the contents of the box as part of the project. Both the original photographs and the new artworks inspired by them will be exhibited in Calcutta and villages of Bengal, Delhi and the US.

Research so far indicates that the photographs were taken by an unknown US soldier assigned to the 10th Photographic Technical Unit of the XX Bomber Command, which operated in the China-Burma-India Theatre during World War II. All photographs are marked by the same hand as 10th PTU and most are dated May 3, 1945. These and the token captions like “temple” or “Indian women” were probably randomly given at the labs where the photographer had deposited his negatives.

“The unit operated in Bengal from 1942-1945. It was engaged in reconnaissance work, taking aerial photographs of the land with special cameras to facilitate a land invasion of Japan. With the end of the war in Europe, the unit was dissolved. May 1945 was a transitional period, when the men were waiting to be reassigned to Okinawa. These images were probably taken then as a personal project. The last photograph of the series is from January 22, 1946, in Okinawa,” explained Alan.

The easy camaraderie between the photographer and the people, the preference for temple architecture and village life over army parades is surprising. “We sometimes wonder whether he may have been an army doctor, which might explain the warmth shown to him by the people. It is clear that this photographer had a respect for the people and the lifestyle he witnessed. He might even be Jewish, as one of our participating artists imagines, one who was elated by the lack of discrimination in India,” Jerri puts in.

The skill of the photographer is evident. “These were not taken by a modern camera that goes click, click, click… these are large cameras and each negative had to be slid into a holder before a shot… so it must have taken both time and deliberation,” said Alan.

One of the striking photographs is that of a three-year old girl with a tattered cloth wound round her waist. Her bangled hand rests on the large pitcher she may have been carrying as she glances sideways at the camera. How old is she today? What if she or her descendants or neighbours saw the photograph and recognised her? Alan and Jerri hope someone will so that they can learn more about the photographer.

Somewhere on the outskirts of the city may lie clues to the identity of the shy, young rustic who accepts a paan made by a middle-aged woman or the young purohit who in 1945 had waited with flowers, incense sticks and holy water, brows knit in impatience as the sahib took a shot.

The background in most photographs is nondescript —huts, courtyards and fields. But in the one with the girl a part of a temple façade is visible. “We realised the structure which resembles a South Indian temple would help us pin the location. But we drew a blank till one day while researching at the American Institute of Indian Studies, Delhi, we accidentally discovered near-identical images of a temple façade on the Net. These new images were from a Balaji Temple built by the South Indian workers of Kharagpur,” recalled Alan.

They have, with the help of scholars like Dr Gautam Sengupta, state director of archaeology, identified other monuments from the photographs like the Dakshin Kali temple and Nandeswar temple in Malancha, others in Balichak, Bishnupur etc.

They have also managed to find partners in contemporary artists and photographers Sanjeet Chowdhury, Chhatrapati Dutta, Alakananda Nag, Prabir Purkayastha, Amritah Sen, Aditya Basak and Sunandini Banerjee and graphic novelist Sarbajit Sen. If one is making a 5minute film on the imaginary biography of the photographer, another is making computer graphics using the photographs and a third is making an installation that causes an interaction between the photographs and the artist’s family album of 1945. “We hope to use the images to encourage mutual understanding through discussions on heritage, development and representation,” said Alan and Jerri.