|

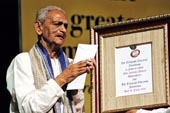

| Krishna Prasad Bhattacharya with the award on Saturday and (below) with students of Nekurseni Vivekananda Vidyabhavan |

|

A 90-year-old led a host of heroes at The Telegraph School Awards for Excellence on the Science City stage

The people of Nekurseni have built this school, yet I am the one getting rewarded for it.” Krishna Prasad Bhattacharya’s voice cracks.

Standing tall at 90 years, he bears the weight of a life remembered. He is all too aware of the missing faces of the people who watched him grow — from assistant station master of Nekurseni railway station (in West Midnapore) to postmaster and then to de facto headmaster, in a village without a school — and with whom he had forged a campus for 2,000 children from nothing but a tiny room in a rice mill in 1952.

Fifty-six years later, when he strode across the Science City stage to be inducted into The Telegraph Education Foundation’s Hall of Fame at The Telegraph School Awards for Excellence on Saturday morning, he missed all those faces.

Now, some other faces inspire Krishnababu: the faces of the children of the village on their way to class. “I had a dream,” he says, sitting cross-legged on his bed in white kurta and dhoti, “that one day, when I grew old, I would watch children walk by my house to school.”

When he arrived at Nekurseni, boys and girls would have to travel 8 or 9 km to the nearest schools at Danton or Belda. “You would be hard-pressed to find a matriculate in Nekurseni,” he recalls.

There was much to be done. “There was nothing but jungle,” he says, looking out of the window in his two-storey house, where the NH 60 now races past, towards Balasore.

Krishna Prasad left Faridpur in 1939 on getting a railway job, and was posted at Nekurseni in 1944. “I knew that every village needed three things: a post office, a school and a doctor.” Within 10 years, he would have a hand in bringing all three to Nekurseni.

He made a trip to Kharagpur, only to hear that it was not possible to set-up a full-fledged post office in the village. “As a rail employee, I was told that if I could give three hours a day, I could be postmaster and they would provide me with a peon.” He gladly took up the task.

A couple of years later, he and station master Jatindranath Goswami started working towards the second need: a school. “There were two rice mills in the village. We approached one of them, and they immediately agreed to set up a small room for us. We would arrange for the teacher, whom they would pay Rs 20 a month.”

Nekurseni Vivekananda Vidyabhavan was born, and it grew rapidly. From about 30 kids from the neighbouring Santhal villages and the mills, within a couple of years there were more than 150 pupils. That’s when the two founders decided to apply for government recognition. Krishnababu pursued it with several trips to Calcutta and the application was finally accepted in 1954. By 1958, they were equipped till Class X.

Another school nearby later ran into problems with their application, and Krishnababu helped them too.

“I spread the word that if anyone was starting a school, I could help with the application. I must have helped at least 30 such schools,” he smiles.

The man who never studied beyond school was even associated for a while with Belda College.

Only a doctor was left on the things-to-do list. When the American Baptist Mission arrived in the area looking for a site for a hospital, a local landowner came forward with about 20 bighas, and the Nekurseni Christian Hospital was set up in 1962. Krishnababu was actively involved, and served for a number of years on the hospital board.

He never strayed far from Nekurseni, turning down promotions which may have taken him away from his school. Suggest to him that he is the true “master of a village” — that’s how Barry O’Brien introduced to the Science City audience — and he insists that if the village has come a long way, it is only because everyone worked together.

“People came forward with land for projects, donated money. The local panchayats also helped, as did the rice mills,” he recalls. “I always said that if your purpose was clear, money would never be a problem.”

His words proved true, at least for Nekurseni. Now, the school building has received a makeover, after the old one was torn down for construction of the national highway. The sprawling campus with a boys’ hostel, football field and pond now has a 30,000 sq ft space for classes at its heart.

Age may prevent Krishnababu from being actively involved, but he watches on with quiet pride. “Our objective was to help children stay in school for as long as possible.”

The school’s pass percentage is nearly 90, despite 70 per cent of students being below the poverty line.

Krishnababu speaks of Jotindranath Goswami, who died in 1963, as the visionary behind the school, and his wife, whom he lost a few years ago, as his backbone.

And, of course, the people of Nekurseni. “Very few people have had so much peace as I have, otherwise I couldn’t have lived so long,” he says, emotion taking over.

And few people have lived so well.

|