|

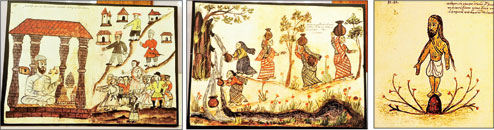

| Illustrations at the exhibition showing (from left) a money changer in Cambay, wives of merchants in Cambay, and a ‘peak’ from which ‘pagans’ sacrificed themselves. Pictures by Anindya Shankar Ray |

It is an unusual collaboration between a famous adventurer and a mysterious manuscript.

Ludovico de Varthema is known to be the first non-Muslim European to enter Mecca as a pilgrim. Not much is known about him except that he was from Bologna. But his own account of his travels, titled Itinerario de Ludovico de Varthema Bolognese, speaks in detail about the many parts of the early 16th-century world that he travelled through, from Mecca to Persia, to India, to Sumatra, and back to Europe, sometimes under assumed identities at great risk to his life.

Ludovico’s Itinerary, at a time the Portuguese were carrying out rapid expansions in the Indian Ocean, is the subject of the exhibition ‘Voyage to India’ at the National Library Art Gallery, March 8 to March 20. It is accompanied by a set of gorgeous illustrations that can be called a strange coincidence. No one knows who drew them, but the illustrations, each of them with a little descriptive card, capture the same Indian scenes from the time that de Varthema came calling.

Driven by the desire to know the world in its particularities, de Varthema had left Venice in 1502. Ludovico, says the brochure of the exhibition, was singular not only in his chronological account of coastal India, but also because he travelled for pleasure and not for commercial or military interests.

The exhibition is produced by National Archives, Rome, and Italian Cultural Centre, New Delhi, in collaboration with National Library and Consulate General of Italy, Calcutta. It was inaugurated by H.E. Daniele Mancini, ambassador of Italy. Swapan Chakravorty, director general, National Library, made the welcome address and Sukanta Chaudhuri, professor emeritus, department of English, Jadavpur University, was guest of honour. Eugenio Lo Sardo, director of Archivio di stato di Roma (national archives), was chief guest.

From Venice, de Varthema had visited Egypt, Beirut, Tripoli, Aleppo and reached Damascus in 1503, where he got himself enrolled in the Mameluke garrison as a Muslim and visited Mecca. After the pilgrimage he deserted the Mameluke guards, an offence punishable by death. Later in Yemen he was arrested as a Christian spy, but was freed through the intervention of a Sultana of Yemen, who was one of his lovers.

One exhibit is a sonnet written by Vittoria, a young woman of the Colonna family, who was a friend and correspondent of Michaelangelo.

Ludovico de Varthema stayed for some time with the Colonna family on his return to Italy. Vittoria compares him with Ulysses, explained Lo Sardo, but she says that if Ulysses had one woman, Ludovico had a thousand.

Ludovico was a star. The book was translated into 50 languages, many of them soon after its publication in 1510 in Rome.

In India, he travelled down the west coast, to Cambay, Chaul and Goa, Bijapur; Calicut, Malabar, Cochin, Quilon, rounded the Came Comorin and reached Ceylon. Then he sailed to Pulicat, north of Madras, then to Tenasserim on the Malay peninsula and to Pegu. From Malacca he returned to the Coromandel Coast.

By around 1506, anxious to return to Christianity and to Europe, he joined the Portuguese garrison at Cannanore. Around 1508 he sailed from Cannanore, touched Mozambique, where a Portuguese fortress was being built and arrived in Lisbon sometime before 1510 when his book was first published. His account became so popular that it was translated into 50 languages, including Latin, German, Dutch, Spanish, French and English.

It was pure chance that an illustrated manuscript, describing the same Indian scenes, was conserved in the Casanatense Library of Rome.

The unknown painter, possibly Portuguese, paints the detailed scenes, from the kingdom of Cambay (Gujarat) down the entire Malabar coast, and the extraordinary results look like a Chaucer’s pilgrim in Indian clothes.

It is also a reminder of how the worlds were in touch with each other long before globalisation.

The illustrations, often in bright earth colours, are full of wonderful observations, and also wonderful errors.

The artist draws men and women busy with their daily lives, farming, money-changing, drawing water, marrying, and particularly, sacrificing themselves and others. Various communities are present, pagans, probably meaning various castes of Hindus, and Indian Christians. A scene showing naked women bathing in a pool reminds of the Indian miniature paintings but somehow the postures are European.

One illustration shows bania women, “wives of very rich merchants of the kingdom of Cambay”, carrying pots of water on their heads. This looks an unusual profession for very rich women. Another depicts “Brahmin goldsmiths”. Yet another paints the holy Hindu trinity: the dark god “Hispar”, Vishnu, Brahma. One wonders who Hispar is.

At the same time, in a wedding scene, the folds of the dancers’ saris are drawn distinctly enough to suggest that they belong to a classical style of dancing.