|

| Roger Federer’s arrival has been like a whiff of fresh air |

Tennis today is perched at the peak of commercial exploitation. Every drop seems to have been wrung out of the game and the players. Jetting across continents week after week, the stale worn-out players endlessly trade top-spin forehands and double-handed backhands. Even for someone who loves the game, it has become boring. There is a robotic dimension about most players. Instinct, passion, flair have been confined to the dull straightjacket of the law of averages.

In the old days, when jets did not zoom across continents in hours and so frequently, each country developed its own style of play, depending on the court surface, climate and national characteristics. But now players, coaches and trainers interact almost every week and a common consensus determines the grip, style and technique to win. This has had a cloning affect on the style of play and led to boredom.

No wonder the crowd’s pine for someone like the unpredictable Ivanisevic who, down a match-point, belted a second-serve ace faster than his first on the Wimbledon Centre Court against Chris Bailey of Britain! Fans flocked to watch Nastase’s divine skills cloaked in frivolity, Connors’ burning passion and intensity, McEnroe’s volatile genius garnished with choice vocabulary.

At the opposite pole stood the iceman Borg. Forged of the finest Swedish steel, his Arctic silence had a magnetic appeal. Then what about Edberg, Tanner and a host of others.

In today’s world, Roger Federer stands alone. His unbridled carefree style with the full array of shots is liberating and a joy to watch. The arrival of Federer has been like a whiff of fresh air in the stagnant world of tennis.

One of the major problems faced by professional tennis players is the proliferation of injuries. It is difficult to find a player who is not carrying an injury. Some years ago I met Budge Patty, Wimbledon champion in 1950, coming out of the men’s dressing-room at Wimbledon. He was shaking his head and saying, “I can’t believe it. It is like a hospital in there”.

Vece Paes, who has travelled to all the major tournaments, told me “80% of the injuries are due to overuse of limbs.” Anyone can tell you that our hips and shoulders are not built to swivel or rotate thousands and thousands of times. The simple truth is that like in all commercially exploited games, there is just too much play.

Our recent cricket series against Pakistan, where there were injuries galore in both teams, provide evidence that cricket is also firmly in the grip of the “too much play” syndrome. All this is compounded by attempts to hustle nature by artificial means to hasten recovery. The players are patched up and sent out to play, sometime resulting in chronic recurrences.

Injuries have become a dominant feature in tennis. How often one reads about players withdrawing from tournaments, defaulting from matches and being treated during matches. It is time for players and promoters to stand back and have a good think at the state of affairs.

Last year, while watching the French championships, I was astonished to see the fitness level of the players. Even in the fifth set of a gruelling encounter on the slow testing clay, they sprinted to retrieve impossible shots showing no signs of exhaustion. On the next day, they were back full of beans! It was amazing. At that time, it never occurred to me that they could be using banned substances.

Later in the year Greg Rusedski, Britain’s No. 2 player who was once ranked fourth in the world, tested positive for the banned anabolic steroid nandrolone and faced the prospect of a two-year ban. Rusedski was furious. He revealed that no action had been taken against 47 other leading players who had failed the test and that he would fight the ban to the bitter end. Eventually, Rusedski was cleared of the charges on the ground that supplements or electrolytes handed out by ATP trainers in good faith was the cause of contamination. Seven players were also cleared last year on the same ground.

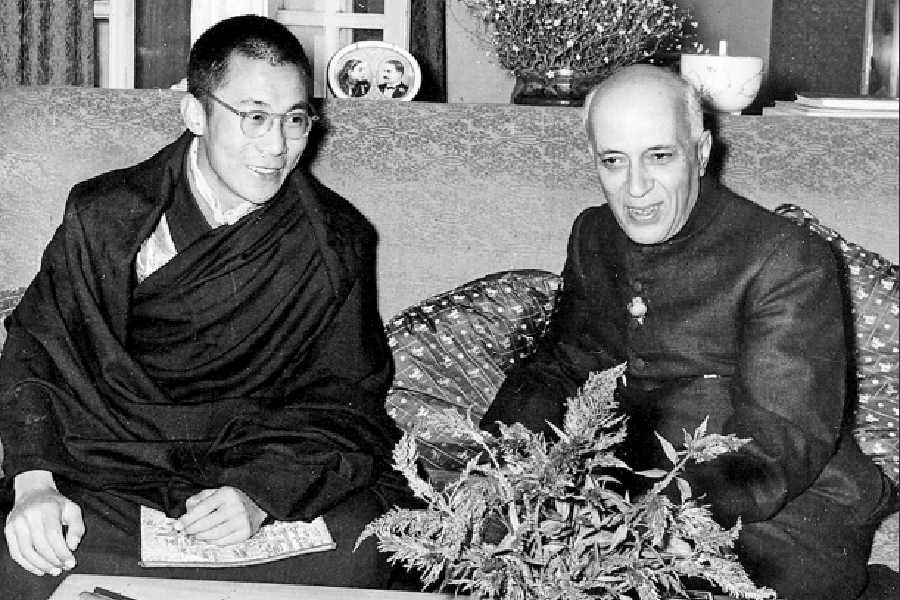

|

| Fans flocked to see the volatile genius of McEnroe |

How could the ATP prosecute them when its trainees had given the contaminated supplements to the players? A leading newspaper in Britain said: “The International Tennis Federation is incredulous at the handling of the growing drugs crisis by the US-based Association of Tennis Professionals and are concerned that Rusedski and seven other leading players who failed tests last year may have been wrongly cleared.” They have asked the world anti-doping agency to look into the reports on the eight cases which were thrown out after the players tested positive for nandrolone.

The policing of drugs in tennis should be put firmly in the hands of an independent body such as the World Anti-Doping Agency. How can the ATP, being an interested party, adjudicate on such matters? Though it is unlikely that drugs in tennis have risen to the sophisticated undetectable levels as in athletics and other sports, the possibility cannot be totally ruled out.

Steroids, undetectable human growth hormones and other supplements give you additional strength, endurance quick recovery and increased aggression! In the bitterly fought matches at the topmost level, where differences in contestant’s standards are paper-thin, drugs can prove to be the trump card. With a million dollars and more of prize-money for the singles winner at the Grand slams, it is a tempting option.

Drug policing has been stepped up and it is reported that both Federer and Agassi were tested 20 times last year. My gut feeling is, matters are not out of control currently and that the malaise is not as deep-rooted as in some other sports where undetectable designer drugs seem to be in common use.

Another ailment that lurks subcutaneously since the amateur days is the demand for appearance money by top-notch players. When tennis became professional, one of the main reasons given was that it would put an end to sham amateurism and make everything transparent.

Top-notchers do not dare ask for appearance money from Grand Slam and other important tournaments, but target vulnerable smaller tournaments. The malignancy lingers on and seems incurable.

If the flagging interest in tennis is to be revived, the authorities running the game (ITF and ATP) have to tackle these problems. The playing schedules have to be curtailed so that the fans are not shortchanged. The French championships are only a fortnight away and victory or defeat will depend on which one of the top players is injury-free.

It is sad to think that the title may not go to the best player but to the lucky one who at that time is injury-free.