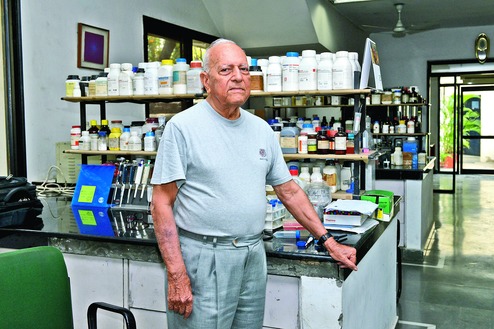

Gursaran Parshad Talwar, now approaching 92, appears excited that the Indian government is once again backing an idea he had conceived more than 40 years ago - a birth control vaccine for women.

From his laboratory - where he still guides researchers seeking new strategies to fight drug-resistant cancers - Talwar is currently tracking efforts by gynaecologists in two Delhi hospitals to get 120 women to volunteer for clinical trials of the latest version of his birth control vaccine.

The efforts and clinical trials are expected to take time. This is Talwar's third attempt to offer what could still become the world's first vaccine for women to prevent pregnancies. His earlier attempts, first in 1976 then in 1994, were punctuated by a rollercoaster of emotions amid deep science.

Talwar, a biochemist and founder-director of the National Institute of Immunology (NII), New Delhi, has tasted the thrill of designing and demonstrating a novel strategy for contraception and experienced the disappointment at how his idea drew scepticism and, at one point, was virtually abandoned.

"Life has challenges, but you can't get buried under them, you have to leap up and tackle them," Talwar told The Telegraph last week. "I will turn 92 on October second this year, and am looking forward to seeing the results from these clinical trials - I want to see if this vaccine performs as well as the earlier version did."

Talwar, who was born in Hissar, encountered his first - and tragic - challenge early. His mother died when he was eight days old, and he was brought up by an aunt whose portrait adorns a wall in his laboratory-office at the Talwar Research Foundation, a laboratory he built through a mix of personal funds and grants from research foundations.

He studied science at the University of Punjab, obtained a doctorate degree working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris and joined the biochemistry department at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, in 1956. There, in the early 1970s, he started searching for a new way to block pregnancies - and picked on human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone produced only after ferti-lisation of the egg and is critical for its implantation in the uterus.

Talwar reasoned that if he could design a vaccine that could generate antibodies against hCG, the body's immune system itself would be primed to prevent implantation - and thus prevent pregnancies. He published his first paper in the journal Contraception in 1976, describing how three out of four women who had received the vaccine he had designed showed antibodies to hCG 11 months after immunisation. The antibody levels declined to near zero in one woman after 16 months, indicating the reversibility of the vaccine's effect.

The publication also generated some scepticism. Even medical researchers asked: Vaccines? They're supposed to prevent infections, not pregnancies. But Talwar, who set up the NII in 1986, persisted and collaborated with doctors in three government hospitals to conduct safety and clinical trials. They gave the vaccine - three injections at intervals of six weeks - to 148 sexually-active women who already had two children and agreed to participate in the trials after informed consent.

The trials between 1992 and 1993 demonstrated the vaccine's safety, efficacy and reversibility. In 1998, AIIMS doctors tracked four women who had taken the vaccine and, after the trial, become pregnant again. Their study showed that the anti-fertility vaccine was reversible and had no effect on subsequent pregnancies or children.

But Talwar retired in 1994 and NII's interest in the vaccine appeared to plummet. "These things happen in this country - an unusual or novel approach is sometimes criticised. But we have to live with this, it is part of our culture," he said.

However, in 2006, 12 years after he had retired, Talwar received a surprise phone call from the US. An official with the Indo-US Committee on Contraception and Child Health asked whether he would want to continue work on the birth control vaccine. He agreed and modified his approach - in the 21st century, he thought, it would be appropriate to design a low-cost, genetically engineered vaccine that could be produced under industrial conditions. He redesigned the anti-hCG vaccine, making it amenable for production in yeast cells also used to make the hepatitis-B vaccine.

After Talwar's laboratory generated volumes of safety and efficacy data through laboratory and animal tests, the Indian Council of Medical Research agreed to support clinical trials. The Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech has agreed to make vaccines for the clinical trials. It will be tested in 50 women for safety and immune response, and 70 women for efficacy at the AIIMS and Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in New Delhi.

"We're in the process of recruiting women - it is not easy, we have to fully inform them about the nature of the clinical trials and what we're looking for," says Indrani Ganguli, a senior gynaecologist at the Sir Ganga Ram Hospital.

But the concept is still likely to encounter opposition. "We need to ask - is it proper to disrupt the immune system to block pregnancy, which is a natural process?" said N. Sarojini, director of the New Delhi-based non-government Resource Group for Women and Health. "You immunise against diseases - pregnancy is not a disease," she said.

Paediatrician Jacob Puliyel at St Stephen's Hospital in New Delhi, who is also a member of the National Technical Group on Immunisation, a panel that advises the Centre on vaccines, said reversibility may not be guaranteed.

"In addition to antibodies, the body also develops memory T cells, another arm of the immune system, that can be activated quickly even after antibodies to the vaccine have waned," Puliyel said. "In such a situation, the immunity - in this case, infertility - could be for life and the risk of abortion will loom all through the pregnancy."

It is possible some women who took part in the earlier clinical trials did become pregnant after the antibodies' titres dropped but, Puliyel said, there is no guarantee every woman who receives the vaccine will respond in this manner. "Take chickenpox, after illness, protection is for life, although some rare people get chicken pox years later."

But Talwar remains enthusiastic. He says the birth control vaccine strategy is the only physiological contraceptive approach for women available that "does not disrupt a woman's hormones, ovulation, or menstrual cycle, or has side-effects such as bleeding." There is, he said, no contraception method "that offers these advantages".