|

One of the vital clues in solving the murder in the first chapter of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code was a disordered Fibonacci sequence. It is one of those sequences that people with even a superficial interest in numbers have heard of. But Manjul Bhargava, the Indian-origin mathematician who won the Fields Medal (a prize as prestigious as the Nobel Prize) this year, says the infinite series of numbers that the West was introduced to in the 13th century has an Indian connection. According to him, the inspiration for the Fibonacci sequence has actually come from the metre in ancient Sanskrit poetry. Bhargava learnt Sanskrit from his grandfather who was a scholar of Sanskrit and ancient Indian history.

“What is sad is that many modern Indian mathematicians do not know that many ancient Indian linguistic works are rich in mathematics,” says Bhargava, R. Brandon Fradd professor of mathematics at Princeton University. “This is because these ancient treatises are not read by mathematicians but artists, linguists and other scholars,” he says. The Canadian-American number theorist drew inspiration from many mathematicians in ancient India, including Brahmagupta who lived in seventh century AD.

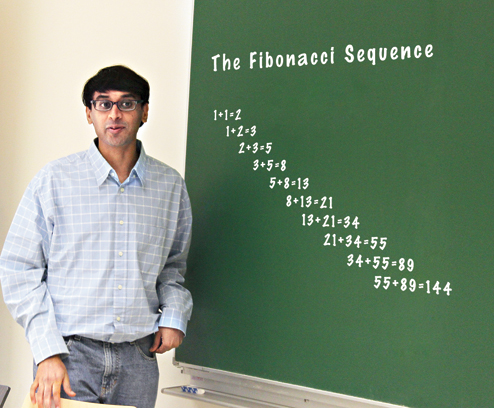

In the Fibonacci series, each subsequent number is a sum of two previous numbers in the series such as 0, 1 (0+1), 2 (1+1), 3 (2+1), 5 (3+2), 8 (5+3) and so on. What is amazing is that nature also goes by the Fibonacci series. For instance, the number of petals in a flower is generally is a Fibonacci number, as is the branching in trees, the arrangement of leaves on a stem and the arrangement of a pine cone.

The Fibonacci sequence has been widely used in the rendition of Indian classical music, says Bhargava, who hails from a family of musicians in Jaipur. “ A lot of mathematicians like music. This may be because they like patterns, particularly stringing together patterns in beautiful ways. Music is nothing but patterns and the arrangement of patterns in an orderly fashion,” says the mathematician who turned 40 in August.

“Tabla playing, for instance, involves a lot of improvisation. A player needs to fit different patterns and sequences into metre. For example, there is a pattern of one beat (ektal) and a pattern of two beats (dotal). Before a performance on stage, the player needs to figure out mathematically what the possible ways of combining the two to create a certain note are so that it is aesthetically pleasing for the audience,” says Bhargava, who learnt the tabla from celebrated maestros such as Zakir Hussain and Pandit Prem Prakash Sharma.

If he hadn’t been a mathematician, Bhargava would have been a tabla player. “At one point in life I had to decide whether to become a mathematician or pursue my interest in playing the tabla,” Bhargava told KnowHow during a freewheeling chat. He was one of the main attractions of the recently-concluded Heidelberg Laureate Forum, a week-long meet where accomplished mathematicians and computer scientists engaged in discussions with talented young people.

Bhargava was introduced to both the loves of his life by his mother Mira Bhargava who too was a mathematician and an accomplished tabla player. He is also interested in magic, particularly in card tricks. He was introduced to magic, he says, by magician-turned-mathematician Persi Diaconis, who taught him during his undergraduate days at Harvard.

“I used to like mathematics as long back as I can remember,” says Bhargava of his childhood, which was spent in Canada. “Even when I was two or three I used to ask my mother about mathematical problems. She always encouraged my questions but often asked me to go and find out the answers myself. When I was eight years old, I wanted to know how oranges could be accommodated in a pyramid of a certain size. In a few months, I came up with a formula which figured that out. I used this formula to find out the number of oranges required to fill in bigger and bigger pyramids,” he says.

“I like the predictive nature of mathematics,” says Bhargava, whose love affair with numbers continues. He was awarded the Fields Medal at this year’s International Conference of Mathematics at Seoul, South Korea, for developing new tools for the study of geometry of numbers. The Fields Medal, the top award in mathematics, is given to mathematicians below the age of 40.

What does Bhargava think should be done to encourage a love of numbers among students in India who usually fear mathematics? The adjunct professor at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai, thinks there should be a drastic change in the way mathematics is taught in Indian schools. “Students should be given a chance to appreciate the beauty of mathematics. Rather than forcing them to rote learn formulae and apply them to a set of problems given to them, they should be set on a path of discovery so that learning mathematics becomes a beautiful experience,” he believes.

Many students in India complain that they cannot do research in the subject they love because the infrastructure is not available. Doing research in mathematics, Bhargava says, is a lot easier. “We do not need large equipment or even a lot of books, unlike other subjects. I often do research while walking around the town or walking in the woods. What I need to ensure is that I take my head with me,” he chuckles.

This academic year, in addition to his regular classes, Bhargava is teaching a course on mathematics and magic at Princeton. In this hugely popular course, which attracts even non-mathematics undergraduate students, Bhargava imparts many a trick, such as sleight of hand, that he learnt from the legendary Diaconis, who is currently a professor of mathematics and statistics at Stanford University.