Zubeen Garg is dead. And Assam is bereft. The rest of India is unable to look away from the scenes of grieving and the small, big and moving overtures to commemorate the man. A newborn elephant in Kaziranga has been named Mayabini after his cult song; tree-planting drives are being organised in his memory; and in the last three weeks, public spaces across the northeastern state have turned canvas for portraits of the man lest anyone forgets to remember.

But not too many outside of Assam can comprehend the shape of this loss, its length, breadth, depth. Like icebergs, that which immediately leaps to the eye is but a fraction of what lies hidden.

“I have heard when Michael Jackson died, the world grieved like this. But in my lifetime, I have never seen anything like this,” says Debojit Saha, who is a singer famed for winning Zee’s Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Challenge in 2005, Silchar boy and Zubeen’s contemporary.

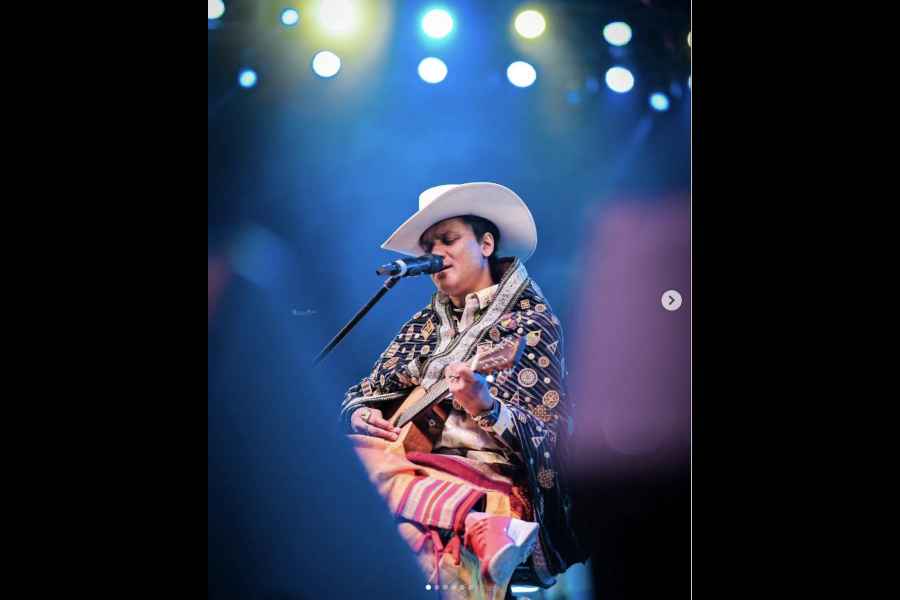

Zubeen Garg died on September 19 in Singapore and since then, his life has been playing out in social media posts ad nauseum. Last interview, early concerts, the Ya Ali clip from Anurag Basu’s Gangster, which mind you was not his musical debut in Hindi films, and his song Mayabini Ratir Bukut. There are AI videos capturing his shifting shape from dapper youth of long hair and leather jackets to maverick dresser of outrageous colour combinations, shaved head and tattoos snaking up skinny arms. Interviews upon interviews — earnest to indifferent to angry. Pithy one-liners — “I am not a king, but I rule”, “mur kunu dhormo nai, mur kunu jati nai”.

Wall painting near the Dolabari Flyover in Tezpur by artist Runal Rajbongshi

It is all out there. Who he is named after, how he gave up his family name, the names of his dogs, his romance in two chapters with Garima bou, the story of his first crush from school days, how his mother wanted him to complete his bachelor’s till the end of her short life. It is all out there. And still it is difficult to put a finger on the man’s appeal for an entire community, across generations, across faith and to an extent even class.

Many of those The Telegraph interviewed said that to understand the place Zubeen occupies, it is imperative to locate the artiste culturally and socio-politically.

Rajib Handique, who is a professor of history at Gauhati University, says, “The winds of change were already blowing in the early 1990s. The Berlin Wall came down and India adopted neo-liberalism. The Ulfa insurgency and counter-insurgency operations deeply affected Assam, disrupting the normal. People were caught in a cesspool of violence, intimidation and corruption. The musical world was taking a turn towards fusion. At such a time, in Assam, Jitul Sonowal’s songs came as a welcome change.”

Zubeen was an accompanist to Jitul. Sound designer Amrit Pritam says, “When I first met Zubeen in 1989, he was 18 and had the reputation of being a good keyboard player, not a singer. He used to play the keyboard with singer Luna Sonowal. Most of the time he discussed music, all kinds of music — Indian, Western.”

According to Imtiaz Saikia, who currently teaches in Oman, not many knew of the extent of Zubeen’s engagement with Western music those days. He says, “I remember the day he parked his yellow Ranger bicycle at the gates of J.B. College and walked towards me excitedly. He took out a gold medal tucked inside his black leather jacket and said, ‘Imtiaz, I won this in Madras, for Western vocal’.” Music producer Utpal Sharma speaks of Zubeen’s interest in folk music, something he picked up while at school in Tamulpur.

Nearly everyone brings up his “spontaneity”, his “bohemian ways”. And you realise that this too set him apart, this too defined his creative impulses. Saikia remembers an episode from their college days when Zubeen picked up a dead bat and stuck it to his denim jacket!

Portrait of Zubeen by Mukul M. Baishya

By 1992, Zubeen was singing in public. Friends recall hearing him at the J.B. College auditorium in Jorhat. Around that time he came out with his debut album Anamika. In a full-page preview of it in Saptahik Janambhumi, Jetabon Baruah wrote: “He will open a new door for music in Assam.”

What was so radical about the music? There is no one neat answer. Critic-turned-film director Utpal Borpujari points out that in Anamika, he put to music a poem by the legendary Hiren Bhattacharya. “Zubeen’s songs carried the energy of rebellion, the poetry of longing and the pulse of a society in transition,” says historian and music critic Swapnanil Barua. He continues, “To him, no sound was alien; everything could be made Assamese if rendered with honesty. A rock anthem from Guwahati carried echoes of the Brahmaputra, while a folk tune bore the polish of global instrumentation. This marked him out as a cultural innovator as well as a visionary.” Former drummer Rajiv Phukan draws attention to Zubeen’s use of various musical instruments. “Probably for the first time, symphonic orchestration made its way into Assamese music,” he says.

Borpujari talks about how Zubeen redefined musical performances. Until then, during shows, singers dressed correctly, stood upright, harmonium in place. But Zubeen dressed and carried himself like a rock star. All this was happening before Bollywood.

Did his Bollywood years — 1996 to 2007 — change him or his place in Assamese society? None of the interviewees makes too much of that chapter of his career. That is not to say they ignore it. Some said he should have spent some more time in Mumbai. Some remarked that the hectic schedule there “exhausted him”, that he was perennially “homesick”. But from the sound of it, Zubeen’s success in the Hindi film industry was neither unexpected nor did it especially endear him to Assam — he was already a superstar.

People don’t seem to talk of Zubeen as a musical sensation in his post-Bollywood, post-Covid avatar. Instead, they will have you note how he helped so many with their medical or education expenses, his initiatives for wayward youth, of how outspoken he was about social issues. He started the Kalaguru Artiste Foundation, named after the revolutionary artiste Kalaguru Bishnu Prasad Rabha, to help the underprivileged and flood-hit. There is much awe for the man too — he stood up to Ulfa’s diktats, opposed the Centre over the CAA and sang Politics nokoriba bondhu. In an email exchange, Sagorika Singha, a researcher working on digital popular cultures of Assam, writes about the Facebook meme collective called Troll Assamese media. The page was hugely popular among Assamese youth and controversial. Singha says, “I discovered the massive popularity of Zubeen Garg amongst its followers as an aspirational, homegrown, talented and generous person pitted against the peasant activist Akhil Gogoi.”

There is criticism too of this Zubeen’s “lifestyle”, but muted and always followed by a “we love him, so we had to point out”. Some mention his failing health with a decibel drop, how he couldn’t always sing when he had to. But all of this, admiration, indulgence, critique, is grounded in a common sentiment — “he was one of us”.

Borpujari says elders of the Mising community believed he was one of theirs because he sang their songs. Recalling Zubeen’s Hindi music album Yuhi Kabhi from the heydays of Indi-pop, Singha says, “For us, as children, it was a thrill to see someone from Assam breaking into the mainstream.” Senior IT professional Sazzad Zahir has Zubeen’s Maya on his playlist. He says, “His songs weren’t overproduced or distant — they felt like they were sung for us, about us.” Neehar Kakaty, who is studying engineering, says, “It is Zubeen who upholds the beauty of our Assamese language.” Bhupen Hazarika’s name comes up, and he is described as “the guiding light”, “the moral compass”. Borpujari says, “We looked up to Bhupen Hazarika, revered him, but Zubeen was one of us.” Friend Mukul M. Baishya says, “Through his creations, Zubeen tried to bind the people of the state by integrating Assam’s diverse culture.”

Rupali Sinha, who has a food stall outside the gates of Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, says, “Zubeenda used to come before 4am, quietly have his food and pay me way more than he had to. He would say, ‘You take the trouble to feed me at this hour’. He understood people like us.” Nikumoni Boro, 24, who works in a café in Guwahati, says, “He helped a lot of people in my hometown Udalguri.” Aboyob Bhuyan, who did an episode with Zubeen on his Untold podcast in September of 2024, tells The Telegraph that whenever someone in Assam started a channel or a show, it was customary to invite Zubeen for the inaugural episode and he almost always obliged. Bhuyan says, “Zubeenda proved that stardom is not about being exclusive.”

In life, Zubeen Garg was many things. In death, he has proven that he was greater than their sum. The man who famously said “moi Kanchenjunga” has now become a mountain of emotion, or a river such as the Brahmaputra he so revered.

Assam’s darling boy is dead. But of course, India must pause.