He walks into the room and is immediately surrounded. You are a little star-struck and very much in awe — not only because you know you’re in the presence of one of the most well-spoken men currently walking the surface of the earth, but also because that quiet assurance he carries is disarming in the gentlest way possible. But it’s not just the intellect that leaves you stumped. It’s the way he carries it — with grace, with charm, and with that unmistakable ease of someone who knows exactly how to hold a conversation without trying too hard.

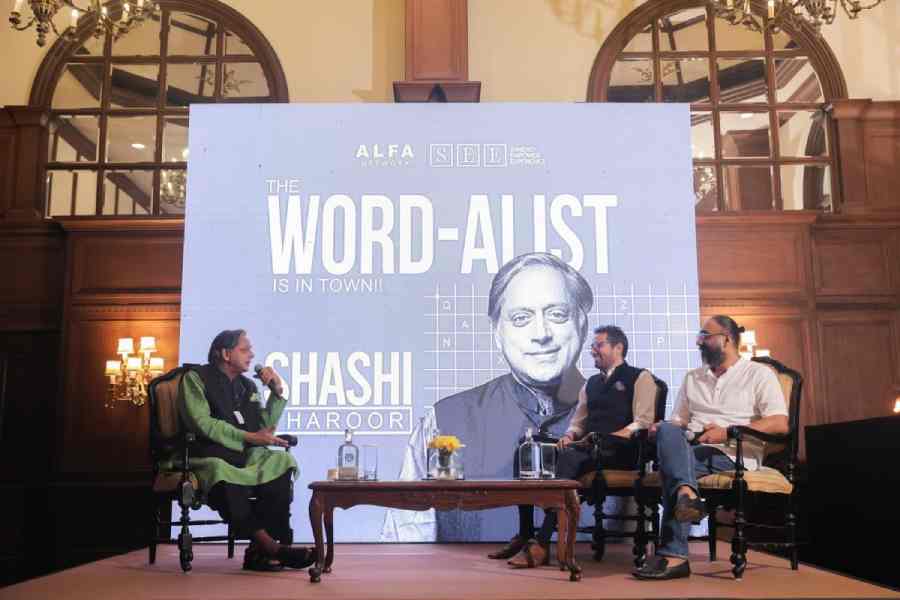

Because Shashi Tharoor doesn’t just enter a room. He commands it, in the most poetic, graceful of ways. Conversations hush. Heads turn. Even the air seems to pause for a moment, adjusting its rhythm to match his Oxford-tinged aura. You suddenly remember every big word you’ve ever known — and forget all of them instantly. Or at least I did. And there, on the night of April 18 at the Taj Bengal banquet, at the beginning of Alfa Network’s first major event of the year since their new chair Ritika Karnani assumed her role, for a session aptly named ‘Shashi Tharoor: The Word-Alist is in Town!’, I am sure plenty of others did, too.

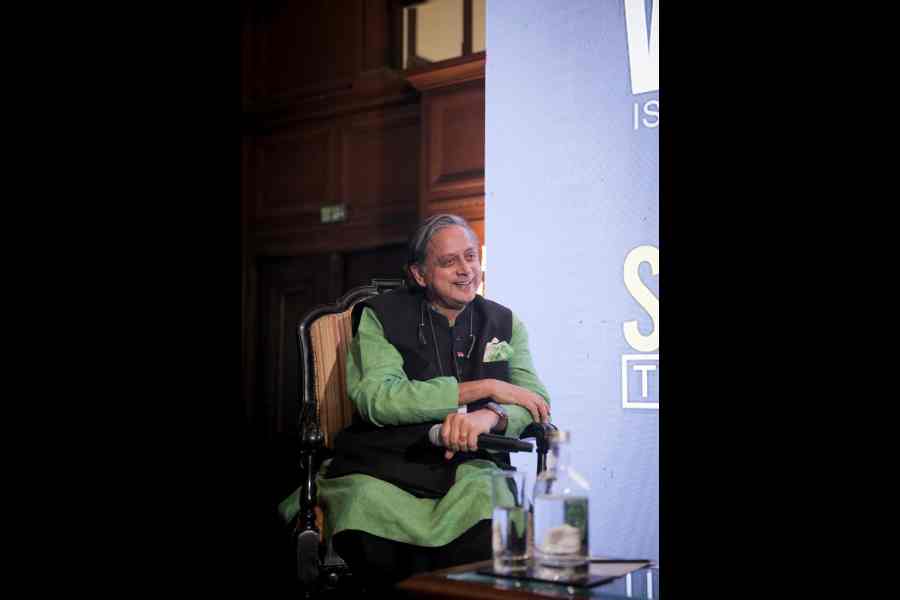

There’s familiarity in Tharoor’s appearance. Hardly ever seen in anything except his trademark kurta, Nehru coat and trousers, the statesman-scholar enjoyed a glass of alcohol before taking the stage to engage in a conversation that went on for two hours and touched not only on Indian history and politics, but also the current political scenario the world over — peppered, of course, with personal and professional anecdotes, wit, and the kind of vocabulary that makes you want to pull out a dictionary. But that’s the charm of the man, and when he wraps up his talk, he leaves the place a hundred times more enlightened than it was before.

Excerpts from the session:

On how the British can redeem themselves for their colonial misdeeds

The answer is moral atonement. I was asked this question a lot in England when my book An Era of Darkness (known as Inglorious Empire in Britain) came out, and I gave them four answers. As a first, acknowledgement of what they have done. A simple sorry. There’s simply never been an apology to India for the wrongs, the atrocities, the killings, the loot, the rape. I don’t think financial reparations are realistic because any credible amount would not be payable, and any payable amount would not be credible. So, let’s drop that idea. A simple apology and sorry should get us started on the right foot.

Shashi Tharoor

The second answer I said was to teach unvarnished colonial history in their schools. They’re in such denial! There actually was a British minister who said Britain is the only country that has nothing to apologise for in the 20th century. Can you believe that? My God! You have the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in the 20th century, the gassing of the Iraqis in Mesopotamia, the murders in Iran…. I mean, there are so many examples they should be apologising for, but they have just painted an unvarnished picture of colonialism. All they know about colonialism is garden parties and ladies in parasols and pretty dresses, and enjoying the crowd. And the other problem I discovered as I went touring the country at the time was that you could do entire A-levels (the highest school degree in England) in history without learning a single line about colonialism. They have to stop doing that.

Third, I said, there are so many museums in London, it’s probably the world capital of museums. Half of them are basically chor bazaars! And the only museum with the word ‘imperial’ in its title is the Imperial War Museum, which celebrates British victories in the colonies. So, I said to them, they need to create a museum that also depicts the experience of the colonised. They’ll get a very different story. But that’s something that, frankly, they’ve been quite unwilling to do. Did you know some 69 per cent of young Britons at one point said they thought the Empire was a good thing and they would love to have it back? Can you imagine? I said, “My God, you’ve done all these atrocities to people and you want to have it back?!” It’s horrendous.

On whether the current generation ought to feel responsible for what their ancestors have done

The current generation is not directly responsible. They are inheritors of a past. We all are. It’s like saying, you know, “I am who I am. So I don’t care what my grandfather did.” Right now, the British are busy selling us tickets to the Tower of London and the British Museum, but what they’re really saying is, “Come and pay me money to see what my grandfather stole from your grandfather.” That’s really what’s going on. The truth is, though, that we have to move on beyond this. I used to say to young people when I addressed them on the subject, “Look, if you don’t know where you’ve come from, how will you appreciate where you’re going?” But I don’t think that we can justify every wrong today on the basis of what happened yesterday. Now we are responsible for our own fate.

Our economy is the same size as Britain’s. We can treat them as sovereign equals and we can just move on. That’s very much my view. So my advice would be to address the fact that we are conscious of the past, but let’s focus on the future.

On his crisp British accent

I was taught by Indians to speak like this in Campion School, Bombay. The irony is that this is the way we were taught to speak. I happen to have a good ear. It’s simply because I pick up the sounds the way I hear them, and I’m able to reproduce them. It’s as simple as that. But it’s still not totally British. I mean, it’s the English accent and intonation in the sense of how words are pronounced, but it’s not the way the British speak.

On communicating in the language our colonisers gave us

The English language is arguably one of biggest legacies Britain’s left behind. And it has given us Indians a global passport, but the first thing to point out is that the English didn’t give us the English language. They had no desire to impart general English education to the Indians. What they wanted was to create a small class who would serve as intermediaries between them and the masses and who would therefore assist them in the process of governance. It is we who saw the advantages of the English language and seized it for ourselves. For every college the English established, there were nine or 10 established by Indians. Calcutta is a very good example of that. There was one college established by the British: Presidency University. Almost everything else? Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

But the Indians understood that English is a useful tool. They realised, number one, it gives us a chance to understand what these guys have studied and what they’ve learned and what they think. Secondly, it gives us access to ideas that will help us to deal with them on equal terms. And third, it’s a way of getting ahead. These people are ruling, we can’t avoid it, let’s know their language. So we are the ones who should take credit for having spread the English language from, let’s say, 0.01 per cent of the population to 2 per cent, three per cent of the population, which is all we were able to accomplish by 1947.

But since Independence, without the shadow of the Englishman on top of us, we realised that English had two advantages for us. First, it was a linked language within our country. When two Indians meet anywhere, even within India, their first instinct is to speak in English until they discover they have another language in common....

Then comes 50 years after Independence, globalisation. And suddenly the realisation that English gives us the key to being able to deal with foreigners. It’s everybody’s second language. If you want to have a German customer or client, or business partner, you can speak English with them. You can’t speak German, the client can’t speak Hindi, but you can both speak English. And that became then a major advantage. And the British tried to take credit for it. You will see articles and books by people like Niall Ferguson saying, “Because of the English we gave them, they have been able to access globalisation and all the advantages of the international economy.” But I don’t give the British direct credit for that. I give them indirect credit. They’ve given us a language which, not so much thanks to them but thanks to the Americans, has become the language of international commerce, international contact, even international diplomacy.

On ‘why he is a Hindu’

First of all, my perspective is based on my reading of Indian history and my appreciation of the kind of country we are. And to my mind, ultimately, there is a tremendous amount to be proud of in our civilisation, a lot of which goes into the roots of Hinduism. We cannot deny the fact that over 2,000 years, we have been witnessing the accretion of a large number of people, ideas, religions, influences from other parts of the world, which were absorbed into our society, which influenced us.

On what politics means to him and why he came into it

Politics is about creating a better country, a better society. If you have a vision of what makes India better, then you should be in politics. If you don’t, you shouldn’t be in politics. I came into politics after a completely different career, but our politics for some time now has been reduced to a politics of seeking support on the basis of identity rather than the vision of a better society.

I do condemn those who came to invade, plunder, loot, and leave, like Ghazni, Ghori, Abdali. These fellows came only in order to attack India to extract what they could from it, but the Mughals, for example, who are demonised by our friends the ruling party, came to stay. Every Mughal king after Babur had a Hindu wife, often a Rajput princess. Every subsequent Mughal emperor was more and more Indian in blood and ethnicity, and they were people who lived here for centuries. And yes, Babur may have sent some money for the upkeep of his ancestors’ graves in Samarkand, but by the time you get to Aurangzeb, Bahadur Shah Zafar and so on, their ancestors were all buried in India. The country they owed allegiance to was India. If they exploited our people and overtaxed them or whatever, it may be they spent the money in India. It was Indian artisans, Indian jewellers, Indian cloth makers whom they patronised. And it was in India that they built and left behind their architecture.

I mean, history is history. You can’t wish away the past. So you really have to ask yourself, what is the use of history? I’m not saying to myself, or to my people, to today go off and punish every Briton they see or go off and attack London for their wrongs. All I’m saying is, acknowledge what happened in the past, know it, and move on. I don’t treat British people any differently today from the way in which I might have treated them if they had not conquered my country. You see what I’m saying?

Today’s Muslims in India are in India. They’ve made their home here. Let us judge them by their conduct, by their behaviour. I’m not saying every Muslim is an angel. I’m not saying every Hindu is an angel. There are individuals who are good or bad, who are extremist or moderate, who are efficient or lazy in every religious identity, every caste identity, every group identity. Not every Marwari is a successful businessman. But the fact is, you can stereotype people up to a point. Ultimately, in living with them, you judge them as individuals.

You know that famous line by Martin Luther King, “Judge us not by the colour of our skin but by the content of our character”? I say the same thing about Hindus, about Muslims, or vice versa.

On whether he will ever form his own party

Fifteen years ago, I would have said yes straight away. Not many people know this, but when I was in college, I was actually a critic of the Congress party. I was a supporter of a party none of you know about, called the Swatantra party. The Swatantra party was a party founded by C. Rajagopalachari and Minoo Masani in 1959, principally on the issue that the Congress party under Nehruji had become too socialist, and their argument was that India needed free enterprise to grow and prosper and develop, and also needed greater liberalism, greater freedom, and so on. If you look at the principles of the Swatantra party, you will see they’re fabulous because they actually believed in all the things that one would want to make the country prosper.

They also had a lovely idea that no other party has ever had, which I would have if I ever founded a party. This last point was, “You are free to believe what you like. We believe in freedom”, and that to my mind is something that’s very good. Today, thanks to the Anti-Defection Law and the way our parties function, no one is allowed to believe anything of their own. Whatever the party says, you have to follow it. Whereas Swatantra rightly stressed on free enterprise, liberalism, democracy, whatever it was.

The party lasted only 14 years, but if I were to start a party of my own, those would be the beliefs and principles. I believe in free enterprise. I believe in freedom of expression. I believe the government has no place in my bedroom, in my kitchen, or at my dining table. I don’t think it should be interfering with the private lives of Indian citizens. I think the government should be an enabling agent, helping businesses to prosper, helping the country to prosper. It should provide the basic infrastructure so that the poor get social justice. We can’t ignore them. There are a large number of poor people in our country, we need to help them.

But coming back to that set of beliefs, the closest I could find when I left the UN and came to India was in the Congress party. And I had a lot of respect for Dr Manmohan Singh, whom I’d known since my Geneva days in the 1980s when he was there for a few years. So when he said, “Come and serve the nation, work with me,” I was obviously inspired and I said yes. Looking back now, I don’t regret that at all. It was the right thing to do at that time. Whether it’s still the right thing is a different matter.

See, in politics, we should basically be accepting that all of us have the best interests of the country at heart. We just disagree about the means of getting there, but I’m not anti-national because I’m anti the ruling party. It’s just for me, India always comes first, and I speak for India. I believe that the country comes first and everything else is second, but sadly for the government, any criticism of them is anti-national. And that kind of thing is not right in a democracy. I think it’s damaging.

On what he thinks of Rahul Gandhi

You know, when I was at the UN, my old boss Kofi Annan told me something very sensible. He said there are no silly questions, there are only silly answers. So there are some questions you don’t answer. My silence speaks for itself!

On the abundant memes made on him: Does Tharoor think his flair for words has become a personal token?

More than I intended to, but initially I played along with it, I must admit. It all started with one tweet. I can tell you what happened: it’s when this journalist did a complete hatchet job on me. And I responded by saying, “This show was a farrago of misrepresentations, distortions, and outright lies broadcast by an unprincipled showman masquerading as a journalist.” I still remember the tweet because I didn’t realise that any of those words were difficult to understand! I’d used them all before. ‘Farrago’ was a standard word in Stephen’s College debates. We used to say, “It’s a farrago of lies,” or “a farrago of false logic,” or whatever. Very common word. And then later that day, there was a tweet from the Concise Oxford Dictionary saying, “Why are suddenly one million people looking up the word ‘farrago’ today? We’ve never had more than six or seven in one week!” And then the answer came to them, that this guy in India had used the word. And then people started opening Twitter accounts calling themselves Mr Farrago and so on.

On whether he thinks he’s made the English language more dramatic: Is it getting out of hand now?

See, either you resent it and sulk, or you embrace it and go with it. I decided that I may as well... You remember a particular politician, I won’t name him, who had been elected on a ticket in alliance with us, abandoned us, and jumped ship to the BJP and remained chief minister, supporting the other side. So I tweeted, ‘Word of the day: snollygoster. First known use: 1845. Definition: a shrewd, unprincipled politician. Latest usage...’ and then the date. I didn’t have to mention the guy’s name, his state, nothing. Everyone understood what I meant. And I’m very pleased to say ‘snollygoster’ has entered the vocabulary of Indian politics. No one was using it after 1845 until that particular day! And I’ve seen it in a number of articles thereafter.

Now, similarly, ‘floccinaucinihilipilification’ (the act of considering something as worthless or insignificant). My publisher said, “Look, your book The Paradoxical Prime Minister is coming out, get some attention for it.” So I deliberately tweeted, “My new book, The Paradoxical Prime Minister, is here. It is more than just a 500-page exercise in floccinaucinihilipilification!” And then I gave the definition of the word below. That tweet got a lot of attention. But then I was saddled with the curse of it for the next three years. Everywhere I went, parents were getting their little toddlers to come up to me and saying, “Tell uncle, tell uncle: floccinauci...” It was a nightmare!

On whether the power of articulation has become diluted in the age of WhatsApp and Instagram

Actually, it is far more worrying than losing the power of communication. People will communicate one way or the other. More important is the power of comprehension. Because what’s happening in this era of WhatsApp forwards is, no one is reading seriously anymore. There have actually been studies demonstrating that today’s young people are not able to engage with complex text and in-depth reading. And this is really worrying.

Because unless one reads in depth, one is not able to gain very complicated ideas. You are then dealing with superficial ideas expressed in simple terms, which are very short, which is what WhatsApp is all about. And that can really make you far more susceptible to propaganda, and to influence other people’s points of view. Because you simply don’t have the background and the complexity anymore to understand that the issue is more complicated than they’re describing, and that there actually are more nuances and more elements to it. That is really worrying.