If Calcutta and Naples are twinned today, it is because Sergio Scapagnini played matchmaker. “It had taken seven years to complete the steps. Now they are officially twin cities,” says the Italian, who was the proposer and the promoter of the twinning.

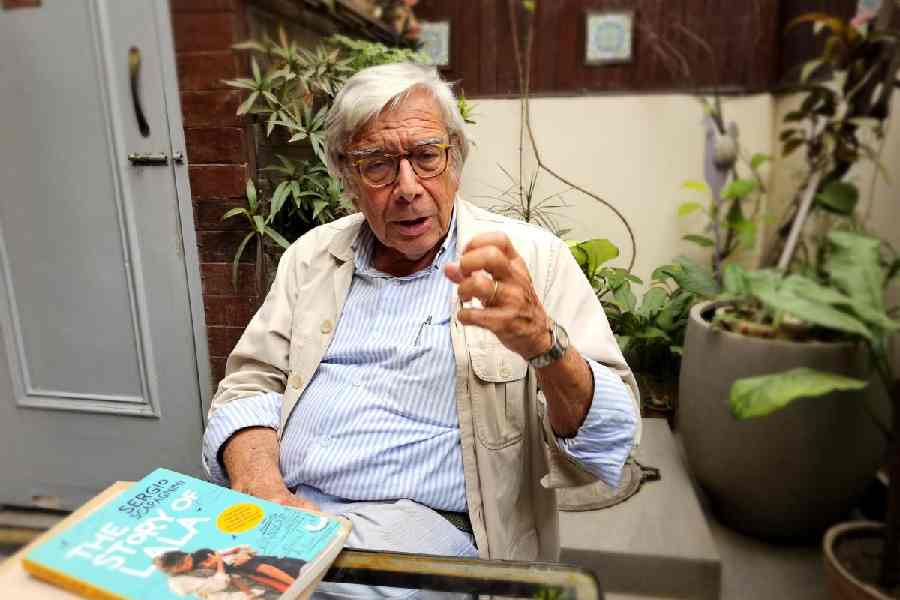

The affable man with a mop of silver hair is seated in a boutique hotel in Ballygunge as he recalls the 2003 visit to Naples by the then mayor Subrata Mukherjee and his seven-member delegation from the Kolkata Municipal Corporation. “He signed the MoU of the twinship with our mayor of that time, Rosa Iervolino. We celebrated the event by inaugurating a statue of Mother Teresa in Naples,” he recalls.

There was also a two-day conference in the Aula Magna (great hall) of the University of Naples L’Orientale. Tara Gandhi, a granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi, sent a poem, titled Napoli and Calcutta, for Scapagnini to read out.

The concluding session was a concert, in presence of the two mayors. On the stage, two groups performed alternatively — Indians sang Tagore songs headed by Reba Som, the then ambassador’s wife, followed by classical music by a Neapolitan group. In conclusion, they played a piece together, celebrating the twinship.

One of the points of commonality Scapagnini had highlighted in the proposal for the twinship was the craft of clay modelling in both cities. “If you come to Napoli around Christmas, we have a tradition of Presepio, for which we create the Nativity scene with little terracotta statues of Baby Jesus, Mother Mary, Joseph, shepherds, angels, cow, donkey — similar to what you make in Krishnanagar with Krishna (for Jhulan). We are the only two cities in the world that celebrate our God this way. The statues are painted by hand in both places,” he says.

In 2023, at the initiative of the Italian consulate general and aided by Scapagnini, Hatibagan Sarbojanin Durgotsab had a Naples corner with two panels on landscapes and handicrafts of Naples, prepared by Prof Vincenzo Gagliardi of the Naples Art Institute. There was also a cut-out of Diego Maradona emerging from the Gulf of Naples.

Scapagnini’s other connection with Calcutta is his friendship with filmmaker Goutam Ghose. “Goutam is now almost a Napoliwallah,” he laughed. “He came for the first time in 1988 while touring with his film Antarjali Yatra. I have a film production unit. I was his distributor. We were in Cannes together. He came to Napoli from there.”

The very first evening, Scapagnini took him to Mergellina, the seaside. “It’s a bit like Chowpatty beach in Bombay. I parked the car in the third lane and went off to buy taralli, a Neapolitan salted biscuit with almonds, fresh from the oven. Goutam was waiting in the car with Khuku (his wife) and (daughter) Anandi. (Son) Ishaan was a baby. By the time I returned, a crowd was honking at the car as it was in the third lane. Goutam laughed and said: ‘This city is very much like Calcutta.’”

First stint

Scapagnini came to India first in 1975-76 on a tourist visa with his wife. His affinity with India grew so quickly that he started coming every three months. His first trip to Calcutta was in December 1980.

In 1984, the chemical engineer resigned from the American multinational company he worked for when he was made its managing director. He was 38 then. “I had started working in India for street children and as a film producer. I wanted to be free to put my energies at the service of a great dream.”

“At the time,” he recalls, “the Italian ministry of foreign affairs had a Directorate for Cooperation with Developing Countries. I submitted a couple of projects to it, which got approved.”

The first project, a combined brainchild of Satyajit Ray, Ghose and Scapagnini, was Roopkala Kendra in Calcutta. “Goutam and I met Ray in his beautiful house. Our idea was to convince the Italian ministry to create a film city in Calcutta. Ray suggested creating a place specialised in social communication to deliver important messages on growth and preventive health to the poor. We described the project to Buddha (Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, the information and cultural affairs minister at that time) who agreed and gave it the name.”

The project aimed to train young directors and scriptwriters to make cinema that would help people and was aided by Father Gaston Roberge. “He had created Chitrabani, a centre for film studies and the first radio station for communication in the villages, and had written books on Ray. While I monitored the progress on behalf of our ministry, he became the local project leader.”

Fr Roberge, who Scapagnini describes as “a great communicator”, flew to Rome to co-direct a two-month training of 15 Indian directors. “The ministry paid for the training and the editing equipment for Roopkala Kendra in Salt Lake. One of the first films they made was aimed at villagers in the Sunderbans, who, in their ignorance, were cutting the mangroves by the sides of the islands. This animation film explained to them that if there were no mangrove, the tide would eat the island like a tiger.”

Enabling move

The other project the Italian philanthropist helped finance was Major H.P.S. Ahluwalia’s Indian Spinal Injuries Centre in Delhi. A Padma Bhushan awardee, Major Ahluwallia was part of the first successful Indian expedition that conquered Mt. Everest in May 1965. Three months later, he went to fight in the Indo-Pak war.

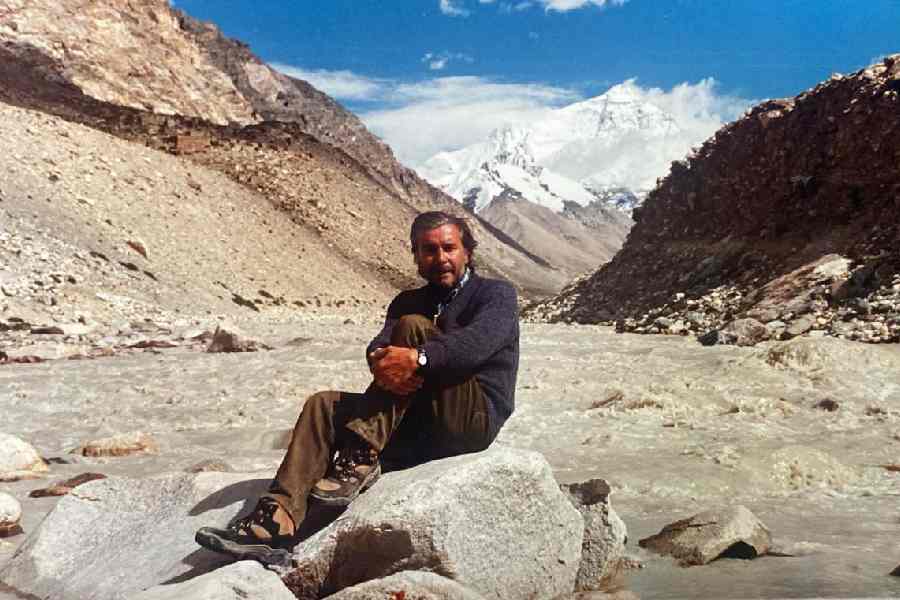

Sergio Scapagnini in front of the north face of Mt. Everest, seen from the Tibetan range, close to the base camp on July 1 1994 during the shooting of Beyond the Himalayas

“On the seventh day, when he knew that armistice had been signed, he took a jeep ride with his group at the Karakoram border, singing happily as the war was over. He even told me the song he was singing — We Shall Overcome. From across the border, a bullet hit him. Perhaps the news had not yet arrived there that the war was over! He was brought by helicopter and operated on. He survived but lost his legs. For a man who had put his feet on the highest mountain to be crippled at the age of 27!” Scapagnini recalls with a shudder. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who “had a great passion for the mountains”, arranged to send the young major to the most advanced centre for treating spinal injuries — at Stoke Mandeville, UK, directed by famous orthopaedic Dr Jack Walsh.

Scapagnini visited the place after he became friends with Ahluwalia and planned a film on his life. “Dr Walsh said he had understood that he needed to transform his patient’s external energy into internal will power. For four months, the youth was trained to recover his spiritual energy. Slowly, he could move mountains in his wheelchair!”

Scapagnini met Ahluwalia two decades after the catastrophe. “He told me that his life’s joy would be if he could give to India a centre like Dr Walsh’s. The dream became a project I took to Rome. After many discussions, I got the money — $30million. Though my friend is now gone (in 2022), his centre remains among the top five places in the world for treating spinal injuries. I cry every time I go there because my first meeting with him was on the soil where the centre stands,” Scapagnini says emotionally.

Call of the Silk Route

The film on Ahluwalia never happened, but what did was more special. “In 1994, I was in Calcutta preparing my first film, Vrindavan Film Studios, when Hari called excitedly. ‘I signed the agreement,’ he said.” Scapagnini gathered that the agreement was with the son of Deng Xiaoping, the leader of the Communist Party of China. “Deng Pufang was a paraplegic who had been thrown out of a window by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. He and Hari had become great friends. They wanted to ease the tension between China and India. So they planned this joint Central Asia Cultural Expedition along the Silk Route, with professors from a university in Beijing and Delhi University participating. ‘I want Goutam to film the expedition,’ Hari told me. But Goutam was busy. I told him the Chinese had permitted us to shoot in places in Tibet where no human has ever been with a camera. So Goutam could not say no anymore. In Delhi, we opened a bottle of whisky and toasted the start of the project, Beyond the Himalayas. It would be a film in five parts, covering 14,000km.”

Sergio Scapagnini and Goutam Ghose pose on the Silk Route with the expedition vehicle.

The expedition started from Samarkand and Bukhara, and ended in Delhi via Lumbini, where the Buddha was born. It lasted three months, with the final month in Tibet till Nepal. Scapagnini hit a domestic hurdle. “I couldn’t go to Central Asia because my wife said: ‘If you go now, you won’t find me when you come back.’ I was already spending so much time in India.” So they made a deal that he would join only in the last leg. “I couldn’t miss Tibet.”

In the course of the expedition in 1994, they understood how extremely central the Dalai Lama still was. “We met a number of people who, on seeing that we were Westerners, secretly showed us photos of the Dalai Lama though we had the Chinese with us. At the time, if you had his photo on you, you risked being thrown into prison. Yet so profound was their love for their spiritual leader!”

Ghose and Scapagnini reached the Potala, the palace of the Dalai Lama, built in the 17th century. “I went near Goutam and asked: ‘Can we ignore what we are experiencing — this fantastic personality of the Dalai Lama?’ We knew we could not highlight him here because the films would have the Chinese as co-producers. But we had all this knowledge and the beautiful images of Tibet. ‘Let’s make a film on the Dalai Lama,’ said Goutam.”

So on their return, Ghose made the films on the Indo-Chinese expedition. But he also started work on another film, titled Impermanence, which became a journey into the world of His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama, whom they later met.

Children of lesser gods

Scapagnini met Sister Baptista in Indore in 1983 and found in her his “spiritual mother”. She had created a congregation called Saint Joseph Sewalaya, where she sheltered rescued children. Scapagnini, his wife and sister-in-law sponsored three of the children.

After eight years of work with Sister Baptista, Scapagnini started out in Calcutta, with Sourabh Mukherjee, the founder of the Young Men’s Welfare Society, as his mentor. “The society picked up children from the streets and gave them the same education as rich boys got, courtesy an agreement Sourabh had with the then headmaster of St Lawrence School, who allowed an afternoon shift after the school’s morning classes.”

Through Sourabh, he met Mother Teresa in 1986-87. “Sourabh came from a family of lawyers and was working with Mother Teresa since 1968. He started a school where street children were educated. In these 50 years, he has groomed almost 50,000 children.”

Scapagnini partnered with Mukherjee through the NGO, Associazione Mondo Amico, in Naples. “The acronym is Ama, which means love. I worked with the great priest of Naples, Don Gennaro Matino, who understood what I was doing in India. We brought young volunteers and gave support, first to Sister Baptista in Indore, and then in Calcutta to Sourabh.”

In 1995, Mukherjee and Scapagnini arranged a visit of Sr. Baptista and Don Gennaro to Calcutta to meet Mother Teresa who blessed the work of Ama in collaboration with its partner NGOs. By then, Mukherjee had introduced Scapagnini to Kallol Ghosh, who now runs Café Positive, among his other ventures with underprivileged youths. Scapagnini visited his outreach programme for children on the Dum Dum station platform and signed a partnership.

“Brother Gennaro raised the money — ₹8 crore — to buy a plot of land with a building on the southern outskirts of Calcutta, which we transformed to Apanjon, an integrated residential project shelter, offering nutrition, treatment and support to children in need. This was a gift from Naples. The campus has a plaque in memory of Lina Matino, Br Gennaro’s mother.”

Sergio Scapagnini addresses the gathering with the Gold Mercury Award kept on the lectern.

Such is Scapagnini’s soul connection to Apanjon that when he was nominated to receive a global honour, the Gold Mercury Awards, he accepted it on condition that he would receive it with the street children of the world in front of the young boarders of the shelter in Calcutta. That was in 2014. He kept Nicolas De Santis, the president of the organisation, waiting for 10 years till the opportunity came in end-2024.

The winter brought Scapagnini to Calcutta for the screening of Ghose’s film Parikrama, which is based on his book The Story of Lala. An Indo-Italian co-production, Parikrama is the first fruit of a treaty between the two countries and is now touring the festival circuit.

Producer Sergio Scapagnini is all ears as Goutam Ghose discusses his film Parikrama at Nandan, with the child actor who played Lala in the film sitted at the centre.

Like so many other meetings in Scapagnini’s India story, the encounter with the street dweller, Lala, was fortuitous.

“I met Lala on February 12, 1988. I used to reach Calcutta via Bombay. My flight was cancelled, and the passengers were put up in a hotel on Juhu beach. I went for a stroll. Many hawkers came after me. I firmly sent them away, saying I wanted to enjoy the sunset. Only one silently followed, with two bags on his shoulders. That was little Lala. Then an old coconut-seller came to us. I always carry a few coins in my pocket, but that day I searched and found none. On watching my action, Lala jumped up and said: ‘May I invite you, sir, for a good coconut?’”

Scapagnini could not refuse the offer and shared the coconut with the boy, who bought it for ₹5. “I was resigned to be shown the young hawker’s wares afterwards. But Lala started telling his life’s story instead — how he saw his father dropping to his knees before the zamindar when the crop failed after a missed monsoon and he was unable to pay back the rent. That made him run away from the village with the dream of making enough money to buy land for his father someday.”

The account became the favourite bedtime story for Scapagnini’s three daughters — Stellina, Sophia and Serena — and his wife Gloria suggested that he write it. When he finally did — and his daughters edited and illustrated it — a friend insisted that it be published. The story of the street child’s resilience got an award in Italy and has since been translated in seven languages, including Bengali. “A great success for a poor chemical engineer who has not written anything in his life,” he said, with a shrug.

As he turns 79 today, Scapagnini wears the name he is referred to in Calcutta as a badge of honour. “Sergiokaka is what I am called and will always be in my long love story with India,” smiled the genial man from Naples.