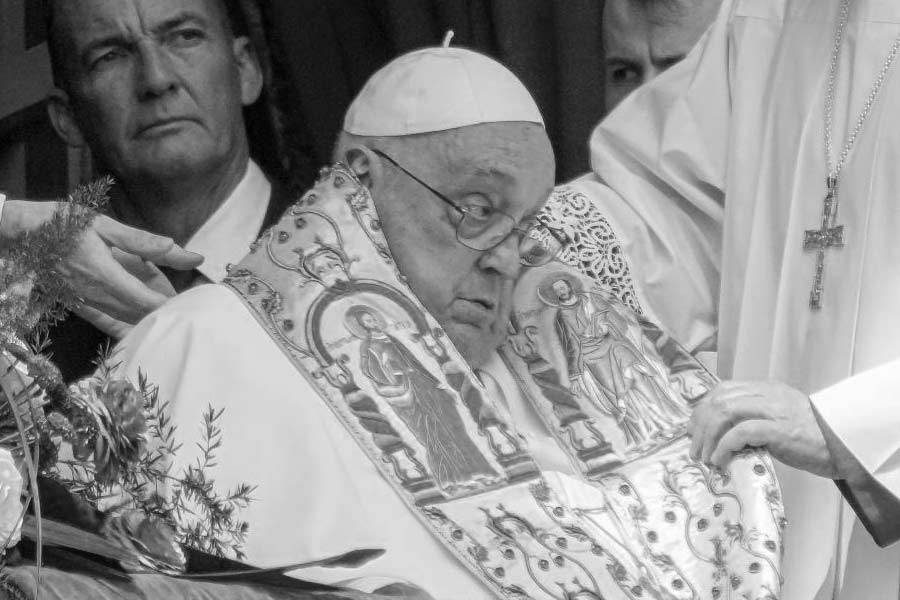

Pope Francis’s death on Monday morning represents the end of an era for the Catholic Church — one marked by rare attempts by a pope to change its image and to give it a direction for the future, only for those efforts to be curtailed by conservatism. The 88-year-old pope, who assumed the religious leadership of 1.4 billion Catholics in 2013, broke with the approach of his predecessor, Benedict XVI, who had steered clear of reforms and antagonised Muslims and indigenous Americans with controversial comments. By contrast, Pope Francis’s tenure was defined by his outreach to communities beyond the walls that the Church had erected around itself for centuries. In his first visit outside the Vatican, he travelled to Lampedusa, the Italian island that is the entry point for thousands of undocumented migrants escaping fear, hunger and war in Africa and the Middle East. Through his stint, he called for empathy for refugees — even criticising Donald Trump’s policies as president of the United States of America that are aimed at evicting migrants.

The first pontiff from the Global South also made an unprecedented trip to the Arabian Gulf, meeting the leader of Egypt’s Al-Azhar Mosque and issuing a joint document on strengthening relations between Islam and Christianity. He refused to judge gay people and said homosexuality was not a crime. As Israel massacred tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza, Pope Francis spoke up frequently, criticising the devastating war at a time when many world leaders who claim to believe in human rights stayed silent. But while the pope allowed women to join the Vatican government, he did not allow them to become priests. He opposed gay marriages. Critics say he did too little to tackle the scourge of sexual abuse perpetrated by priests, often against boys. Still, Pope Francis’s legacy will be defined by his efforts to pull down walls. Will his successor strive to remove the barriers that had held Pope Francis back?