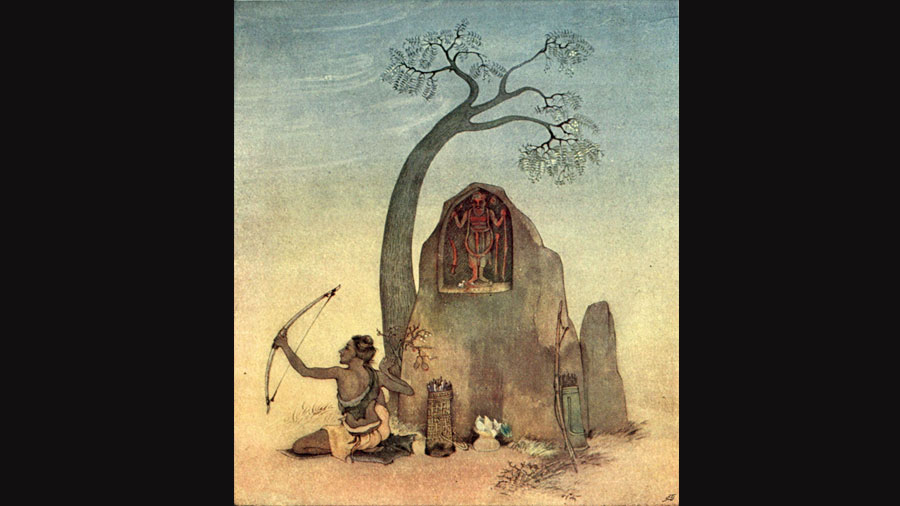

When Ekalavya made a clay image of Dronacharya, he called to life a teacher from whom he longed to learn but who wasn’t there for him. Drona, the trainer of princes, was an absent teacher to the Nishad archer, a strange mentor in an invoked symbolism. Was this an early instance of remote learning? But what can change the fact that given Ekalavya’s social position, Drona did not want to be his teacher at all?

But Ekalavya wanted him nonetheless. He refused to take Drona’s rejection as final. He created Drona’s presence mimetically, calling the guru who rejected him by inscribing spiritual life to his crafted form. The physical price he had to pay in the end for this spiritual invocation is well-known. But it remains important to note that the paradoxical absence-turned-presence of the great teacher becomes part of Ekalavya’s own growth. Great mentors teach even when they are absent. For those of us fortunate enough to have willing mentors, their distant presence is always a source of mentorship long after they cease to teach us formally. Once created, the images never dissipate.

What happens when a teacher dies?

I’ve had such teachers in my life. In the last few years, a few of them have died. Each death has been an intimation of my own mortality — of my growth, aspiration, and in the end, the entirety of my being. With the falling of each image, a part of the old student crumbles. It initiates the anticipation of the day when this practitioner, too, will crumble and wilt away.

Why is the mortal image of the teacher such a powerful one?

The novel of education — variously called the coming-of-age story or the bildungsroman — claims a peculiar empathy. Perhaps because it’s a kind of aspirational change with which most of us can identify. Childhood is the otherness that was once our self. Growth is the kind of aspiration, or oppression, which we all experience. What is more attractive than a young person trying to make their way in the world, growing, falteringly, on the way, sensitive to the nuances of one’s making?

The ultimate dream is to live one’s whole life as an endless bildung, where one never stops growing, never reaches the maturity that closes future promise. Where one falters and rises and learns forever, where one is never a master but always a student, secretly at least. This can happen when one’s livelihood is touched by love, if one’s professional practice remains amatory forever.

One of the deepest intimations of one’s own mortality in a life of ceaseless bildung comes when one meets the death of one’s mentor.

In many ways, my growth as a writer began that moment when in the first-year college classroom, the tall, prophetic figure of P. Lal gave me a note with a sentence in his lyrical, calligraphic hand. He had enjoyed the short story I had shared with him and wanted to see more. Through more notes and a contract crafted with the same personalized aesthetic, I arrived at the publication of my first book.

The trailblazing poet and teacher of poetry always said that the great source of Shakespeare’s poetry was the iambic pentameter, the meter to which the human heartbeat would scan. In 2010, the news of Professor Lal’s death in Calcutta reached me in California in a disembodied way, via an email from Rubana Haq addressed to a small group of people. The message contained the remembrance that Professor Lal lived with the cautious memory of Yudhisthira’s definition of the most wonderful thing in the world: to watch friends and others passing away and yet thinking one would live forever. My parents had left young and had taken my childhood with them. Professor Lal took with him another phase of my growth, one of early trust in my potential as a writer, everything that got me going in this life.

The life Professor Lal sprouted in me looked for the pursuit of creative writing in the United States of America. In the last years of the last century, a Master of Fine Arts was still an unusual bet for a college student in India. But far away in the American Midwest, Wendell Mayo, a writer of magical short stories set behind the Iron Curtain, responded to my hesitant correspondence and reading my stories, welcomed me to a fully-funded place in the MFA. Slowly, I sensed the opening of a lifelong vocation, the miraculous transformation of a passion to material labour.

Wendell mentored my writing, suffered my virgin enthusiasm on seeing snow for the first time, and took me out for coffee when my father passed away unexpectedly, 12,000 miles away. He remained a distant mentor after I graduated, reading manuscripts of my novels and in a memorable gesture, asking me, one day, to blurb the collection of stories that I didn’t know would be his last. Eighteen years after my MFA, I returned at his invitation to read from my second novel after its US release. When I walked him to his car after the dinner following the reading, he was happy, if a little quiet.

The Facebook post that announced Wendell’s unexpected passing later that year came a few minutes before the personal email I received from his wife, whom I’d never met but who clearly knew of my special relation with him. In Delhi at that time, the news of his passing in rural Ohio hit me sensorily. Why, I had walked with him to his car just a few hours ago! Was this the intimate end of a transcontinental relation spanning nearly two decades? With him was gone a long stretch of writerly growth — from early stories sketched in college in Calcutta that brought a vote of confidence from 12,000 miles away, to the request to blurb his own stories of the dark humour with which Communist Europe reappeared in small-town America.

Then death and disembodiment entered our lives in the form of a pandemic, and we slid into a phase where deathbed farewell became a fiction even for the beloved in the same country. A striking thinker and mentor, Lauren Berlant, passed away, flooding the internet and academic social media with memories and tributes. The death of a mentor was a blow to the ongoing bildung of many across the globe.'

While grading a tutorial essay, Swapan Chakravorty taught me the difference between intellectual muscle and intellectual ‘flab’. I remember his unique expression etched in red ink. I’d travelled many years with Swapanda, from the intimate mentoring of the university tutorial to his advisory reassurance in the library committee of the university where I now teach — till he left us this September. Having reached a point where I see my own students start their academic careers, I now wonder if it’s too late to imagine a ceaseless education of my own. Once again, the passing of a teacher takes me back to past moments of birth as much as it gestures towards a future where this education continues, more denuded and impoverished than before.

Saikat Majumdar is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University