“This is my theory”, a young, Dalit, female respondent stated forcefully while defending her individual views about the state of politics in the country in an informal conversation with me. She is a college dropout living with her family in one of the most deprived neighbourhoods of Delhi. I was curious to know about her ‘theory’ and kept pushing her to elaborate it. She did not have a firm grasp on English vocabulary to flesh it out. Yet, it was clear to both of us that she used the term, ‘theory’, rather consciously to convey a set of things — a general overview of recent political events, an explanation of the processes that produce them, and an anticipation that such episodes are likely to happen in the future.

As a student of political science, I was happy to get this self-conscious theoretical reflection. It confirmed my belief that theory-building in politics is inextricably linked to real-life events and, precisely for this reason, the subaltern not merely speaks but also theorises her life and the world in which she lives.

However, as a teacher of politics, I find her reply to be deeply challenging. ‘Political theory’, which is an integral part of the discipline of political science, is presented as an abstract, sober, difficult, and eventually demanding domain of intellectual inquiry. There are certain unwritten requirements to be able to do political theory in India’s elite university system — a workable and sympathetic understanding of Western philosophy, an unconditional admiration for European thinking traditions and political institutions, an ability to speak English in a particular accent and, above all, a sharp memory to remember the ever-evolving bibliography, which must include the names of foreign authors, their famous books, and articles.

The government-sponsored project to decolonise Indian knowledge has severely affected the intensity of these established norms. The search for a decolonialised, unadulterated Indian political theory has already begun to discover the origin of all modern ideas in the realm of ancient Indian traditions. For that reason, the older requirements of doing political theory are being revised and reinvented. One must now have a sincere and uncritical reverence for ancient Indian traditions for doing what is popularly called comparative political theory. In this framework, the purpose of political theorisation is quite straightforward — Indian knowledge ought to be compared with Western political traditions to prove the former’s superiority as the ultimate repository of human wisdom. Despite this significant change of orientation, the political theory in our university system is still revolving around the English-dominated, bibliography-oriented intellectualism. This means that one kind of essentialism that glamourises Western political theory is being conveniently replaced by another form of essentialism in the name of swaraj in the realm of ideas. The scope of political theory is so restricted that there is virtually no space for recognising the empirical realities at the grassroots as sources for serious theoretical reflections. This is exactly what the political theorist, Gopal Guru, had in mind when he described the pernicious divide between theoretical Brahmins and empirical Shudras.

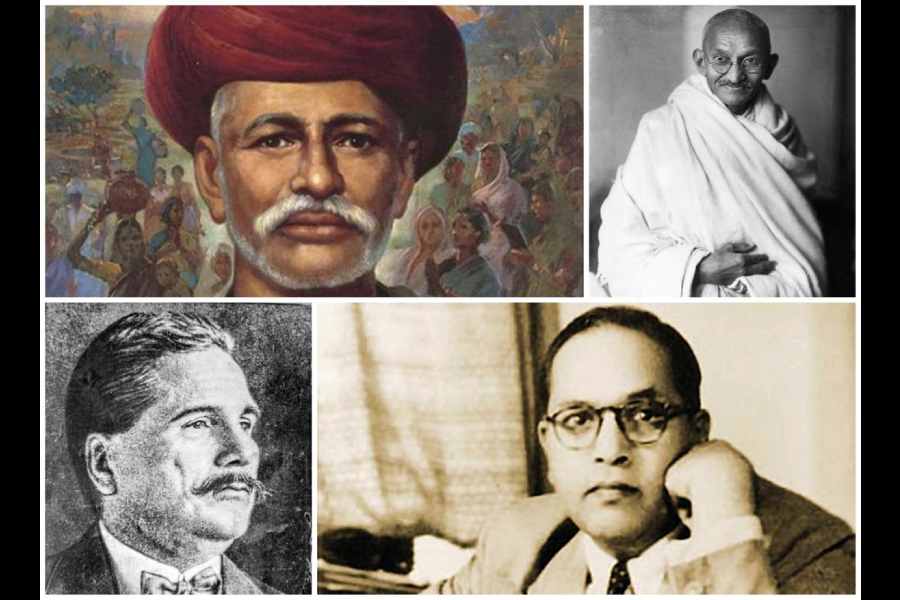

The theory, which my female respondent highlighted, does not originate in the realm of the university system. It underlines the existence of a very different, historically evolved, and perhaps more vibrant public life of political theory in India. Our national movement, it is worth noting, was not merely about achieving political freedom. There was a serious commitment to produce innovative political ideas. In this schema, political leaders also functioned as public intellectuals to communicate with two very different sets of political stakeholders — the colonial State, which could only be addressed in a conceptual language embedded in Western political theory, and the Indian communities, whose political universe was deeply associated with religious traditions and cultural values. This peculiar context forced the nationalist elite to use Indian intellectual traditions and Western political ideas as possible resources to evolve a political theory that could address the anxieties and the aspirations of Indian communities. B.R. Ambedkar’s Annihilation of Caste, Muhammad Iqbal’s controversial, long poem, “Shikwa”, Mahatma Jyotirao Phule’s Gulamgiri, V.D. Savarkar’s Essentials of Hindutva and M.K. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj are relevant examples to demonstrate the public life of political theorisation in colonial India. These texts were primarily written for the general public with an assumption that such an engagement would lead to an informed political mobilisation. Recognising the fact that a vast majority of Indians were almost illiterate and written texts would reach only the educated population, the political elite used public speeches as an alternative mode to disseminate political ideas. These efforts created a vibrant public life for a people’s-oriented political theory.

This process continued to survive after Independence. Political parties gave a lot of importance to what they called political education in the early 1950s. In an ideologically divided political universe, it was necessary for them to disseminate their positions and resolves. Two developments, however, were entirely new in postcolonial India. Competitive electoral politics based on universal adult franchise led to a new kind of professionalism in politics. Winning elections to form the government become the primary consideration for political parties. It became important for them to recognise voters as rational political consumers. The normative-ideological resolves eventually became the tools to legitimise uncomfortable, professionally-motivated political moves. This inherent contradiction between electoral professionalism and ideological self-representation severely affected the capacity of political parties to contribute to political theorisation. The growth and consolidation of the university system, on the other hand, produced an equally alienated fraternity of academic professionals who gradually moved away from the actual world of politics.

This apparent failure of political parties and academic professionals in producing relevant political theorisation has not yet affected the public life of political theory. This is because it has reinvented itself in a significant way. One finds serious attempts to theorise political questions in the realm of literature produced in Indian languages. Authors like Omprakash Valmiki, Geetanjali Shree and Banu Mushtaq offer us political insights that are theoretical in nature. This is also true about social media platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, and X. Many active users produce highly creative interpretations of political events. This vibrant public presence of political theory needs to be further cultivated. There is a need to establish a bridge between the academic world and public life. Only then will we be able to make complete sense of my female respondent’s self-confident claim — “this is my theory”.

Hilal Ahmed is Professor, CSDS, New Delhi