“Every evening our heartfelt desire was to sit around Thakurda and listen to stories. The whole day would be spent in studying, running small errands for our mothers and grandmothers, in school and in games. At dusk, we would spread a shower of learning all through the house by reciting our lessons very loudly... But for how long?... A little into the evening, all our uncles would leave... for their clubs or card games. That was our chance. We hurriedly put by our books. Now the head of the house was — Thakurda.”

The translation is mine, from a story in Bengali in one of the Puja annuals for children from Dev Sahitya Kutir that constituted one of the many joys of the autumn festival in the past. They spilled over with stories, poems, plays — Bidhayak Bhattacharya’s plays about Amaresh were a must, even if you did not always like them — articles, adventures, historical episodes, discoveries, inventions, sporting achievements, myths, legends, fables, even picture tales or comics. Each hard-covered brick-like volume was a treasure trove, carrying something for everyone, from the child who has just learnt to read stories to the curious or dreamy older teenager. The thrill of receiving one was indescribable; it even had a special gift page where the loving aunt or grandfather could write your name.

Each year’s annual had a different name and cover, every time a surprise. The contents on its glossy pages were meticulously detailed: first came a list of writers, and then the works themselves, under heads such as ‘Unpublished poem’, ‘Unpublished essay’, ‘Life story’ — one could be “Sri Ramakrishna and Michael” — or ‘Story’, ‘Long story, ‘Comic story’, ‘Comic poem’, ‘Animal story’, ‘Ghost story’, ‘Mystery story’, ‘Travel story’, ‘Thrilling story’, ‘Robber story’, ‘Devotional story’, ‘Hunting story’, ‘Magic’, ‘Science’ and so on, endlessly, leaving the young reader glowing in anticipation.

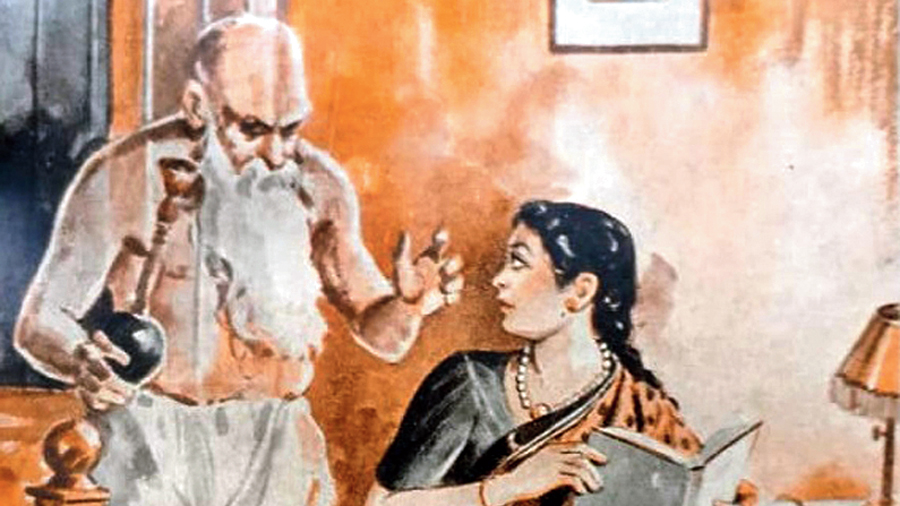

That was one of the deepest pleasures of those Pujas forty or fifty years ago, the ‘heartfelt desire’ for new experiences even if from the pages of a book. Some of the greatest and most well-known writers of the time wrote for children, so adults were encouraging, maybe indulgent. I was unaware then that I was reading many works that I would later find were modern classics. The style of the contents seems delightfully quaint now, yet it offered a kind of basic idea of genres and moods although most children now would find such black-and-white compartments obsolete. The pictures would seem old-fashioned too, but the illustrators were quite brilliant, creating images and dramatic moments that would remain impressed on young minds. Who can forget the woman stretching out her arm through the kitchen window to a lime tree at the end of the yard while cooking for a visitor who faints as he realizes that she is a spectre? (A foreign hand? Behind the tale, that is.) The pictures, too, with their story title and caption — “The Skeleton”: “Hariharbabu said, ‘How did you know all this?’” — had their own contents column under heads indicating the number of colours: three, two or one.

These volumes were clearly intended to delight and teach together; the enjoyment smoothed the way for the carefully woven moral values to sink in. Much of the material would be considered politically incorrect today: Thakurda longs for his hubble-bubble even after death, and Mukulrani, the narrator, is his favourite granddaughter because she dresses his tobacco exactly the way he likes it. The ghost’s repeated appearances overcome his son’s scientific incredulity and he goes to Gaya for the ritual to quiet the restless spirit. Gender roles are usually problematic, but surprisingly, not always so. In those decades following Independence, historical narratives and biographical sketches were also informed by nationalistic feeling. Stories and accounts of developments taken from the West opened up fresh horizons for the reader, while the fillers were substantial. One series of fillers, titled “Amar bani anlo jaara” or “Those who brought immortal words”, selected anecdotes from the lives of writers ranging from Homer, Chaucer and Shakespeare to Bjørnson and Tagore to present their works and times. “Golden accounts” described works such as “Walden”, Jane Eyre, Doctor Zhivago or the Mowgli stories, while “Gems and Pearls” offered quotations from ancient Indian texts with context and explanation. Meanwhile, there were other Puja numbers, too, of children’s periodicals such as Shuktara, Rang Mashal or Sandesh. No child could be blamed for believing these to be limitless riches even if she did not read them all. An addiction had begun.

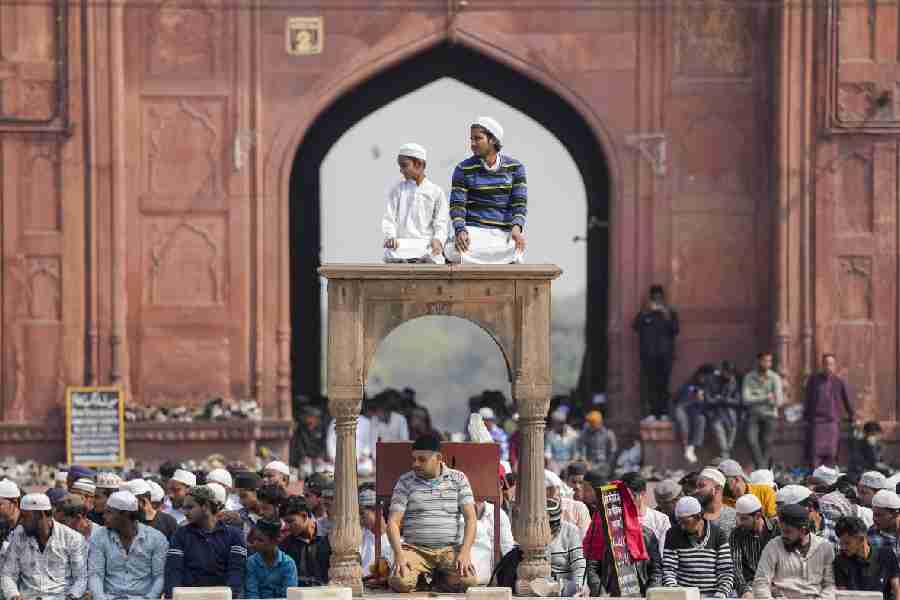

Pleasures keep changing even when the occasion for them remains the same. Not that the baroari Durga Puja has remained the same in spirit, presentation and funding sources ever since, supposedly, 12 young men, the baro iyars, began worshipping the deity outside the family home in the public arena. That was in the second half of the 18th century; there is a disagreement about the exact year. The pleasures then were probably rambunctiously different, even if Hutom of Hutom Pyanchar Naksha is taken with a fistful of salt. If fun fairs, jatras, ‘cultural programmes’ and the gorgeous array of street food during the Pujas nowadays hark back to the noisy carnivals of the earliest public pujas that, according to Hutom, bustled with jesters and buffoons, resounded with half akhrai and kabigan competitions, he sharpened his wit most on the absurd conduct of intoxicated patrons, their pride in masses of animal sacrifice and their grotesque taste in apparel.

The Pujas allow many kinds of enjoyment even today. Aesthetic ingenuity — individual talents blossoming within tradition — created images made of buttons or nails or bottle caps for a time, leading on to ‘theme’ Pujas with their incredible pandals, amazing crafts and lighting, and marvellous illusions. Seniors unable to leave home have matched younger people in pandal-hopping courtesy their television for many years, and this time, with the pandemic forbidding crowds, it was even possible to offer anjali digitally. That apps offered all-round tours of each venue is a sure indication that the deity smiles on technological advance.

Yet this time it was almost like a touch on a pause button. The Calcutta High Court’s strictures combined, possibly, with some apprehension of the damage Covid-19 can cause as well as the scarcity of transport thinned down crowds for most of the festive days. Defiant exceptions notwithstanding, the general impression was of a kind of sadness, so lacking in the usual uproarious goodwill that sweet shops had to scale down production. A sudden silence muffled the addictive frenzy — a mix of worship, pleasure, togetherness, dressing to the nines, competitive social media representation and admiration of idols, pandals and lights — that the festival generates nowadays. Even the dhaks seemed muted.

Yet even in the pause, some other addictions tend to cling. In the misty past, there would come a season when the youngster graduated from the children’s Puja annual to the grown-ups’, the mysterious sharadiya number of adults’ periodicals. It was a joyful rite of passage, the perpetuation of a now unbreakable habit. That sharadiya number has not shed its allure for many, even if it has to be disinfected. The deity was kind enough to allow online orders this time for those unable to leave their homes. Irresistible temptation. Does the addict’s pleasure in continuity spring from memory or from the hope of happier seasons?