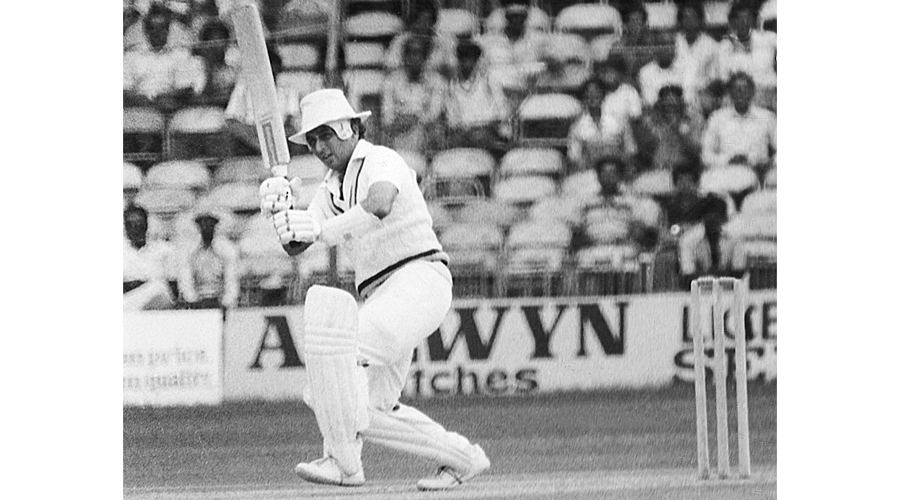

My classmates and I were thirteen when Gavaskar saved us from second-rateness fifty years ago. He scored three half-centuries, three centuries and a double century in four Tests in his debut series. He rounded off his tour with a hundred and a double hundred in the same Test. 774 runs for the series... who is to say he wouldn’t have scored a 1000 if he had played all five?

We used to play book cricket during lunch breaks in school and make runs on that scale. Gavaskar scored those runs in real matches, on tour, against the West Indies, in a winning cause. 774 is the highest series total notched up by a debutant in all of Test cricket’s history. Sometimes, figures do tell the whole story.

On the subject of numbers, he was 5’4¾” tall. If you were thirteen and desi in 1971, you were likely shorter than that. This made Gavaskar practically one of us. He was, like the small Indian bodybuilder, Manohar Aich, our very own World Champion, Short Man Class.

Between 1975 and 1980, when my cohort was in university, Gavaskar was the greatest batsman in the world. He scored a staggering 18 centuries in that time. There were periods of drought before and after this purple patch, but there was a sunburst of runs in the last two years of his career, and he signed off with 96, a masterclass in playing spin bowling on a turning pitch, in a game India lost to Pakistan.

It is patently the case that Gavaskar is the greatest Test batsman India ever produced, but even if it weren’t, my generation, which came of age during his prime, is unlikely to concede the point. Many of us still date our young lives by the landmarks in his career.

I remember, for example, the year that I did my thesis viva simply because it was the summer of the MCC Bicentennial match when Gavaskar scored his only hundred at Lord’s. He had announced his retirement from international cricket the evening before when he was not out on eighty, so celebrating his hundred the next morning was a strange, elegiac business. I was furious when the contest was allowed to devolve into a carnival match because it diminished this last achievement.

Along with his cricketing achievement, the reason Gavaskar became a hero to young people in the Seventies was that he took the trouble to build a persona for himself. He wasn’t just a creature of cricket, he was a public man in his own right. Bishan Singh Bedi was and remains the most independent-minded and outspoken Indian cricketer ever, but he was one of a generation of cricketers mentored by the Nawab of Pataudi. Gavaskar seemed interestingly self-made, an opening batsman who announced himself to the world as the finished article.

There was an assertiveness about Gavaskar, an awareness of his public, that set him apart from his contemporaries who tended to live within the constraints of a relatively poor and poorly administered sport. Gavaskar was undeferential about cricket’s shibboleths; he was, for example, dismissive of the fetishization of Lord’s as sacred ground. He was rude about India’s cricketing establishment while still an active player — he once famously called Indian selectors ‘court jesters’ — and there was a pugnacity to his on-field manner that gladdened the hearts of young fans.

There was a perverse thrill in watching him walk off the field in 1981, taking Chetan Chauhan with him, in protest against Australian umpiring. It was the wrong thing to do as Gavaskar acknowledged afterwards, but I couldn’t help thinking that when Arjuna Ranatunga threatened to walk off many years later in 1999, after Muralitharan was called for throwing by an Australian umpire and won that argument, a cycle of South Asian civil disobedience had been brought to a successful conclusion.

The most interesting part of Gavaskar’s persona was his writing. In a cricketing culture where players take their cues from the politicians who run the BCCI, it’s hard to imagine a young player writing an opinionated memoir. Gavaskar published Sunny Days in 1976 when he was in his mid twenties. It reads like a first draft that needed an editor but it is, for all that, an invaluable account of a young genius’s coming of age.

That missing editor might have blue-penciled the racism of Gavaskar’s description of hostile Jamaican spectators in Kingston: “All this proved beyond a shadow of doubt that these people still belonged to the jungles and forests, instead of a civilised country.” This shouldn’t be excused by gesturing at the casual prejudices of a bygone age because it was called out by readers and reviewers of the book even then. But it is fair to say that this was an isolated instance of prejudice never repeated either in the book or subsequently.

The important thing about Sunny Days is that Gavaskar wrote every word of it. This was unusual because most cricketing memoirs are ghostwritten. Mansur Ali Khan, the Nawab of Pataudi, had published a slim book in 1969 called Tiger’s Tale, but it was, in the tradition of cricketing memoirs, an ‘as told to’ effort. Sunny Days gives us its author warts and all and it’s worth the price of admission for its brusque description of Lord’s: “Quite frankly, I don’t understand why cricketers are overawed by Lord’s. The members are the stuffiest know-alls you can come across, and the ground is most uninspiring. It slopes from one end to the other. I shuddered to think of it as the Headquarters of Cricket!”

In a world where players either speak in cricket corporatese or tweet on demand or stay mum for fear of displeasing their political masters, it’s good to have a hero who used to speak his mind. At a time when cricket was a precarious livelihood, when cricketers depended on the generosity of individual and institutional patrons, Gavaskar’s forthrightness was both unusual and brave.

Recently, when Wasim Jaffer was accused of communalism by a cricket administrator in Uttarakhand, most of his erstwhile teammates didn’t say a word in support or solidarity. In 1993, during the riots in Bombay, Gavaskar ran down from his terrace to rescue a Muslim family cornered by a violent mob. The distance in time and temperament between those two events is the distance between two worlds.

To watch Gavaskar receive a cap commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of his extraordinary debut from Jay Shah was strange, like watching a dystopic film that mashed these worlds together. As the young Gavaskar’s contemporaries and admirers, it’s down to us and our memories to keep those worlds apart. That past was a foreign country; they did things differently over there.