White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings: A Tibetan Tale of Love and War

By Tsewang Yishey Pemba, Niyogi, Rs 495

Do not judge a book by its cover. At least not this one. White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings: A Tibetan Tale of Love and War, written by Tsewang Yishey Pemba, the first Tibetan to become a doctor in Western medical science and also the first Tibetan to write fiction in English, is a vivid, riveting novel about the life of the Khampas from Nyorang, a fierce, old, warrior tribe in Tibet, who resisted the Chinese occupation till the last. The book cover, a composite illustration of a Buddha, Tibetan prayer flags and serene white cranes, predicts in no way what leaps out — a people feared for their bloodthirstiness and love for vendetta, as well as honour and independence, in equal parts. The title, too, seems misleading: the book is not a romance-nostalgia package; no Lost Horizon. Rather, it is a calm, restrained and finely detailed account of an isolated people facing sudden, violent extinction of their way of life, almost as moving and heartbreaking as Chinua Achebe’s great novel on the same theme, Things Fall Apart.

This way of life, more than anything, is held together by religion, the Buddhism that is practised in and preached from the nearby monasteries, which can also be extremely wealthy, corrupt and decadent. It is the mid-1920s. The Nyorang Khampas — they are a beautiful people, tall and strapping, who enjoy a wonderfully liberated sexual life to boot — attract the eyes of the outside world as a degenerate and sinful lot in need of redemption. Specifically of Christianity. A young American couple set up shop in Nyorang to spread the message of their “One True God” and start wholesale conversion.

A strange thing happens. The couple’s arrogance hardly faces any resistance. The ancient religion of the land is large enough to accommodate other peaceful gods. At the most the couple inspire slight contempt. A monk finds Christianity “childish and uncomplicated”, nothing “like the breath-stopping knife-edge of Tibetan Tsannyid contemplation”, which inhabits and transcends Being and Non-Being, and then The Void, and then The Beyond of the Void. It is elusive, beyond the comprehending powers of the human psyche that attempts to understand all phenomena.

But such a religion, profound, complex and sophisticated, is also fragile. On the one hand, it resists science. Children die in Nyorang from measles and the Stevens, the American couple, who advocate modern medicine, are blamed. On the other hand, Nyorang, capable of easily assimilating spiritual enterprises — the Stevens’ Christianizing mission disappears quietly into the larger scheme of things and they happily allow their son, their only child, to grow up as a fierce, lusty Khampa warrior — is hopelessly inadequate when it comes to dealing with things such as Mao’s marauding People’s Liberation Army. Armed with guns and Dialectical Materialism, it marches on to the mountain tops, and attempts to liberate the common people from their oppressors — capitalists, merchants, landlords and priests. The monasteries, built on the Supreme Triad of Awareness, Contemplation and Understanding, can hardly withstand the onslaught of another Trinity: of “Makasu” (Marx), “Lhinning” (Lenin) and China’s own Chairman Mao. Nyorang does not even comprehend what it is being liberated from. Life was tough here, but not unhappy, and not absolutely without prosperity. Most important, the Khampas were a free people.

But is this the end? Who knows? Time moves differently in cycles of history and eternity. Besides, Tibet still stands.

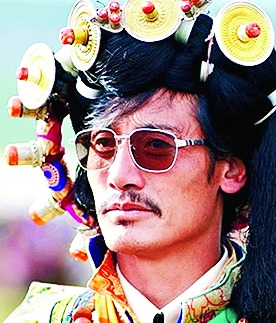

Pemba’s prose is simple, precise, but evocative and reflective: an entire, exuberant world that stands on its brink is brought to life. The narrative is straightforward, but the book offers a remarkable gallery of portraits: the wise Tharsel Rinpoche, the large-hearted chieftain Ponpo Dragotsang, his son Tenga, an alluring young man with a touch of the noir.

A little grudge. The characters sometimes seem to get buried under large chunks of history. Some editing could have helped.

The author of the book was a remarkable man. Pemba, a recipient of the prestigious Hallett Prize from the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, had set up Bhutan’s first hospital. He wrote White Crane in his last years, before his death from cancer in 2011. The novel was published posthumously. It certainly deserved a better design.