India and Pakistan were born at the same time, cut from the cloth of the same Empire. They inherited a common political, economic, and cultural legacy. Yet, in the now nearly eight decades of their existence, their fortunes have markedly diverged. The Indian economy has advanced more quickly; its per capita income is now almost twice that of Pakistan. India has stayed united, whereas Pakistan lost its more populous eastern wing in 1971, which became the sovereign nation of Bangladesh. India holds regular and fiercely contested general elections, whereas in Pakistan the timing and outcome of elections are decided by the generals.

Why has India done so much better than Pakistan? Hindu supremacists like to claim that this is because of the intrinsic and essential superiority of their faith over Islam. In fact, the truth is otherwise — it is because our founding fathers (and mothers) turned their backs on religious prejudice and religious triumphalism that we turned out somewhat differently from Pakistan. The Indian Constitution rejected ancient Hindu models of kingship in favour of a political system based on one person, one vote. It also rejected traditional hierarchies of gender and caste. And it refused to merge faith with State, even though Pakistan was in the process of doing so. Finally, our post-Independence leaders strongly emphasised the importance of modern science in cultivating rational thinking and promoting economic progress. (Even if Muhammad Ali Jinnah were to have been in office for as long as Jawaharlal Nehru, it is unlikely that Pakistan would have had centres of excellence comparable to the IITs or the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research).

These nurturing values of democracy, pluralism, and intellectual open-mindedness were not always upheld as they should have been. Democratic freedoms were held in abeyance during the Emergency of 1975-77. Kashmir and the Northeast witnessed excessive State violence. There were periodic attacks on minorities, and periodic outbursts of xenophobia. Yet these values stayed intact enough to ensure that once the license permit quota raj was dismantled in 1991, it led to two-and-a-half decades of impressive economic growth, which would have been impossible had India been territorially fragmented, run on autocratic lines, or become a theocratic State.

By the same token, Pakistan could not take advantage of the economic opportunities offered by the post-Cold War world because the military became even more important in politics, and because radical Islam became even more significant in everyday life. Pakistan’s international standing was further damaged by its sponsorship of terror in India, its hosting of Osama bin Laden, and its role in nuclear proliferation.

Though they chose different paths, in the global imagination, India and Pakistan were sometimes still spoken about in the same breath. This was largely because the two countries had fought three wars over Kashmir. However, by the early 2000s, India had pulled so far away in economic and political terms that scarcely anyone spoke of the ‘Indo-Pak question’ anymore. India had effectively, and it appeared definitively, de-hyphenated itself from Pakistan. There was even talk of India being instead coupled with China, as in the idea of ‘Chindia’. While China’s economic rise was more substantial, India’s democratic and pluralistic credentials made it an attractive alternative to governments, investors and ordinary citizens in Europe and North America, and in Japan as well.

Now, however, in the wake of the terror attack in Pahalgam, and our government’s response, it appears that the hyphenation which so diminishes our country is back in use again. Donald Trump has explicitly equated India and Pakistan, speaking of them as two equally ‘great’ nations which he had good relations with, successfully persuaded to agree to a ceasefire, and hoped to trade with so long as both behaved themselves. To add insult to injury, Trump even offered to mediate in the ‘thousand’-year-old Kashmir dispute, as, apparently, the wise and honest broker between two equally recalcitrant parties.

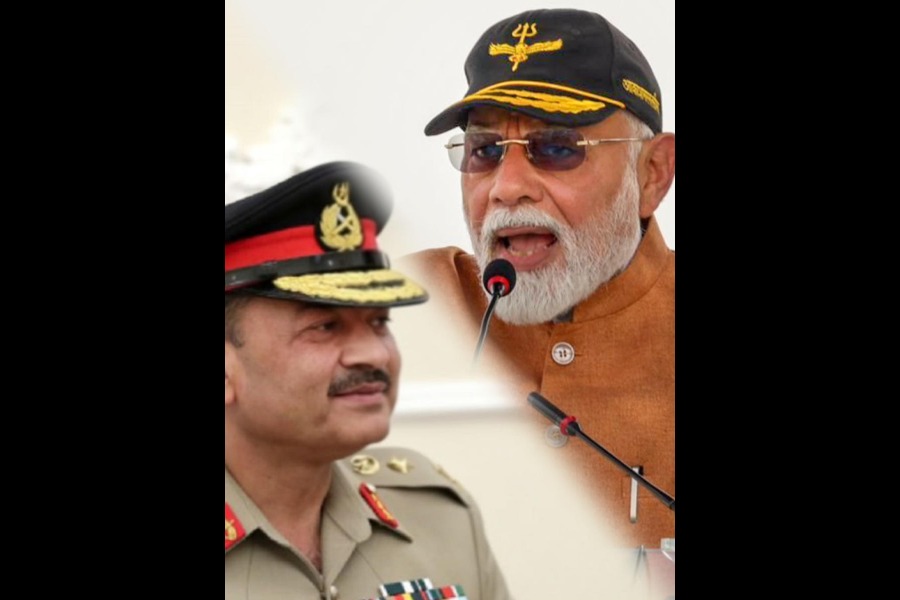

Trump is an erratic and unpredictable character, driven above all by personal vanity. Nonetheless, he is the president of the world’s richest and most powerful country, with which India has vitally important economic and political ties. Hence, we should take his ramblings with some seriousness. Nor should we altogether ignore the more subtle invocation of that dreaded hyphen in reputable sections of the international press. On Saturday, May 10, when India and Pakistan were actively exchanging missiles and drones, the Financial Times printed a long background report on the conflict bearing the headline: “Two religious strongmen clash”. The two men in question were Asim Munir and Narendra Modi; one presented as a devout Muslim who aggressively represents his country’s interests, the other as a devout Hindu who acts similarly on behalf of his country. Another article in the same newspaper spoke of “Narendra Modi’s… obsessive enmity towards Chinese-backed Pakistan.”

Our jingoistic heart bristles at such comparisons. It insists that there can be no equivalence between a State that exports terror and a country that produces CEOs of top global companies. However, while India remains, in the aggregate, a much better place to live in for its citizens than Pakistan is for its citizens, we should nonetheless ask ourselves — might it be that we have regressed in recent years? Would the presidents, Bush, Obama or Biden have ever coupled India with Pakistan, or offered to mediate on Kashmir? Would the Financial Times have ever referred to Manmohan Singh, Narasimha Rao, Rajiv Gandhi, Deve Gowda or even Atal Bihari Vajpayee as a “religious strongman”?

Speaking both as a historian and as a citizen, I would argue that India has indeed regressed in the past decade. We still hold regular elections at national and provincial levels, yet there are legitimate concerns about whether these are as free and fair as they once were. Large sections of the media have become vehicles for State propaganda. Our regulatory and investigative agencies are extremely partisan in favour of the ruling party. So are BJP-appointed governors in Opposition-ruled states, undermining our federal structure. Our democratic credentials are further vitiated by the gargantuan personality cult of the prime minister, built and maintained at vast public expense.

The democratic deficits mount; as do attacks on our secular and pluralist ethos. The symbolic value of having a female Muslim spokesperson during the conflict was quickly dissipated by disparaging remarks made about her by a senior BJP leader; though he has belatedly apologised. The brave and brilliant Mohammed Zubair, lauded for his fact-checking when the missiles were flying, has since faced death threats. It remains to be seen whether the demonisation of Muslims in recent years, by both the Noida media and Hindutva ideologues, will abate in the coming months. The arbitrary arrests and bulldozing of homes in Kashmir in the wake of the Pahalgam attack are not a happy augury. And as for that characterisation of our prime minister as a ‘religious strongman’, nothing gave it more credence than his role as master of ceremonies at the inauguration of the new Ram temple in Ayodhya.

Even as our democratic and secular fabric has frayed, our economic progress has stalled. The gap between China and India is now so large that the phrase, ‘Chindia’, has dropped out of circulation. Smaller countries such as Vietnam have taken greater advantage of the West’s desire to relocate global supply chains away from China.

As I have previously stated in these columns, I do not presume to be any sort of expert on counter-terrorism. I shall not therefore wade into the debate on whether there could have been a wiser response to the barbaric attack on tourists in Pahalgam, or what lessons our armed forces can draw from the several days of intense exchange of fire across the international border that resulted.

My concern here is what the representation of the crisis in the international arena should teach us. How should we react to the renewed attempts to hyphenate India with Pakistan? The default option of the unthinking jingoist is to retreat into victimhood, to blame George Soros and alleged ‘urban Naxals’, and to then defiantly insist that India still is, and always will be, Vishwaguru, Teacher to the World. The thinking patriot, on the other hand, would begin a process of self-examination. The past decade has witnessed a steady rise of authoritarianism and majoritarianism in India; it is this that has prompted these fresh comparisons with the neighbour from whom we were, metaphorically as well as literally, separated at birth. We should therefore look closely into the mirror and ask whether it is past time that we rededicated ourselves to our founding values of democracy and pluralism.