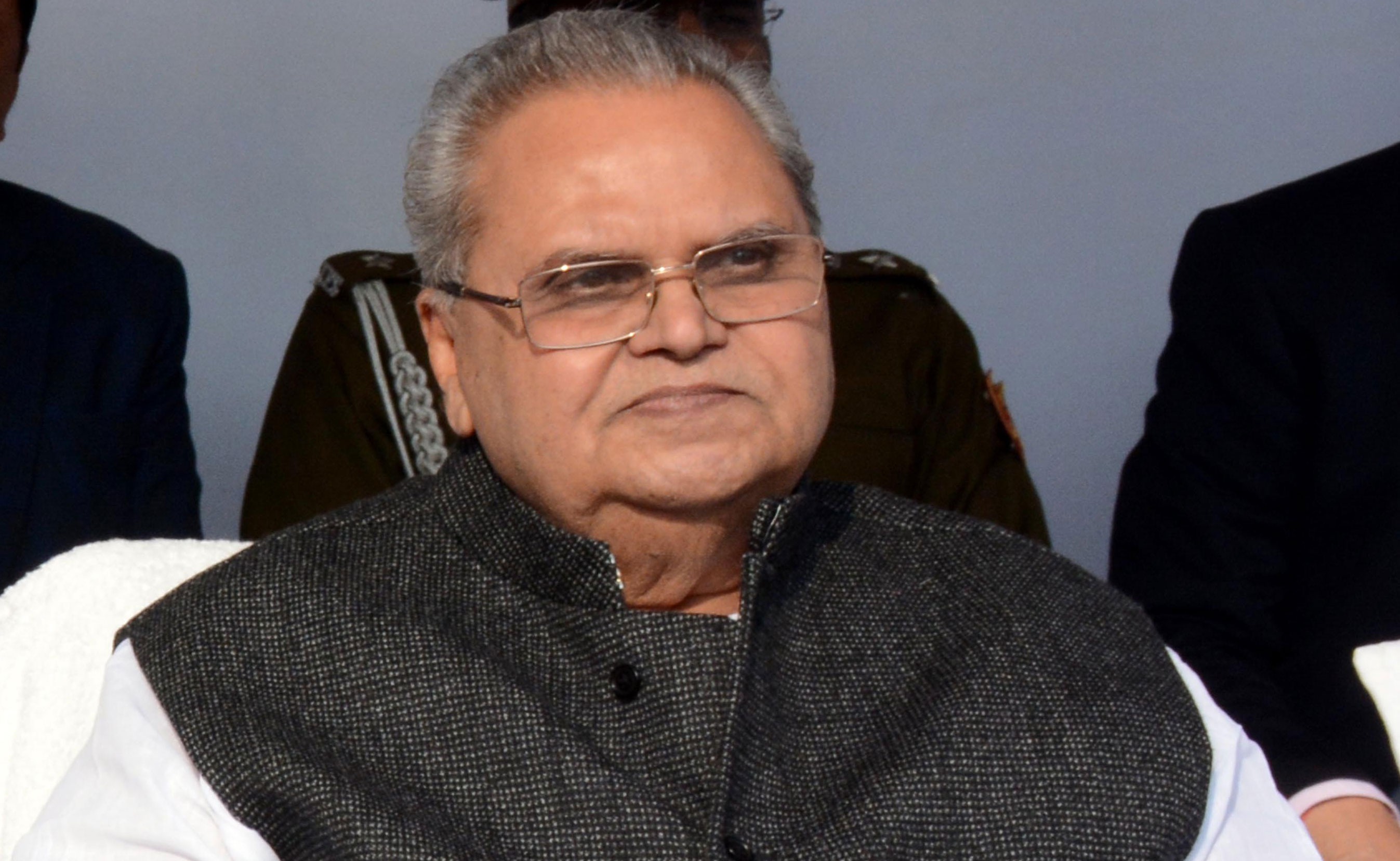

Democracy is a colourful business. The hues that make democracy colourful represent the distinct ideologies of the parties that constitute a democratic set-up. There is, however, a common shade shared by the rivals: this is the colour of opportunism, an element that seems to have become integral to Indian politics. Recent developments in Kashmir have borne out this fact, once again. The governor, Satya Pal Malik, dissolved the assembly after the National Conference, the Peoples Democratic Party and the Congress, principal opponents of the Bharatiya Janata Party, decided to come together to stake claim to power. The House had been kept in suspended animation for months ever since the BJP walked out of its testy marriage with the PDP. Mr Malik’s reasons for dissolving the House are illuminating. The governor apparently feels that political parties with opposing ideologies are incapable of forming stable coalitions. Perhaps the governor had the BJP’s plight with the PDP in mind. But in the course of his condemnation, Mr Pal conveniently chose to gloss over several facts. Indian politics is replete with examples of political parties coming together for the sake of governance. The Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) alliance in Karnataka is an example. The BJP has managed to wrest power — Goa and Manipur can be cited as two examples — by cobbling together unlikely alliances. Governments at the Centre, too, have been rainbow coalitions. Power is certainly the light that draws political moths of all shades. But these formations also enable political parties to learn to coexist, thereby deepening the roots of democracy. Mr Pal’s argument has another flaw. The assembly had not been dissolved for five months, strengthening suspicions that the BJP was seeking to find a way in by engineering splits in rival camps. Yet, the deed was done at the first signs of the Opposition closing ranks. Mr Malik’s haste could raise questions about the objectivity of the governor’s post.

This is not to suggest that the BJP’s opponents had pious intentions. For the PDP, wrecked by internal dissent, the dissolution has come as a godsend, helping it avert the fracturing of the party. After pushing the governor’s hand, the NC and the PDP would be hoping to use the time gained to prepare for polls. The eagerness of political parties to prioritize their own interests over those of citizens lies at the root of Kashmir’s problem.