Over the past few months, Lutyens’ Delhi has been in the eye of a political storm over the building works in the Central Vista project. The ongoing building activities have been questioned by those opposed to the Narendra Modi government on two counts.

First, many Opposition politicians have described the public expenditure during the Covid-19 pandemic as evidence of the government’s misplaced priorities. Since the project aims at being completed by the time India celebrates the 75th anniversary of Independence, it has been dubbed as Modi’s ‘vanity project’ and even challenged — unsuccessfully — in the courts. Critics have even gone to the extent of comparing the new Central Vista scheme with Albert Speer’s unfulfilled plans for a monumental Germania in the heart of Berlin to celebrate Hitler’s Third Reich.

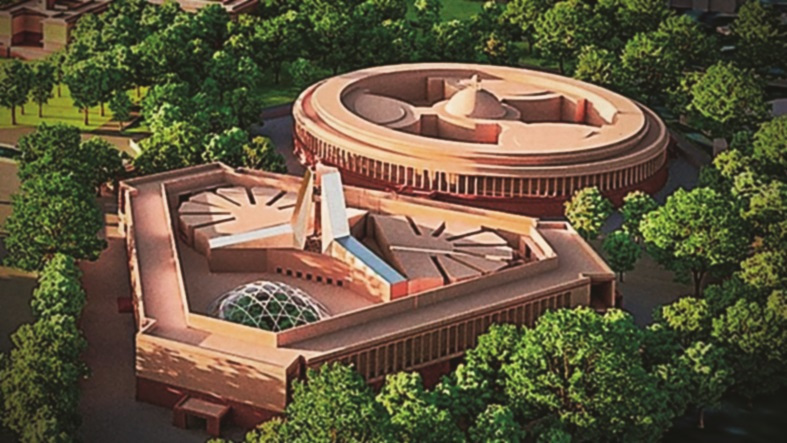

Secondly, there have been questions raised on the aesthetic merits of the project. The likes of Sir Anish Kapoor have called Bimal Patel, the Berkeley-educated, Ahmedabad-based, chief architect as “third rate” and the London-based Daily Mail even went to the extent of describing the new buildings, particularly the new Parliament building that will come up alongside Sir Herbert Baker’s famous circular structure, as examples of “bad taste”. Kapoor, whose connections with contemporary India have been casual at best but whose fierce opposition to Modi dates back to May 2014, even suggested that the project was inspired by the prime minister’s blind hatred of anything remotely Islamic. Whether either Sir Edwin Lutyens or Baker — the two main architects who designed the new city a century ago — were inspired by Islamic architecture is, of course, undocumented.

The storm over the Central Vista project is not the first occasion on which the urban landscape of New Delhi has been drawn into controversy. A brief examination of some of these earlier points of friction may be instructive for a more rounded understanding of the present issues.

First, the decision to transfer the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, announced by the King-Emperor at the Coronation Durbar of 1911, was fiercely contested. The Opposition, led in the main by the former viceroy, Lord Curzon, contested the wisdom of moving from “the English city with which it has been associated for 150 years to the dead capital of Mahomedan kings…” The European business community of Calcutta was equally miffed and The Statesman ran an editorial, “Hardinge Must Go”, that likened the viceroy to Siraj-ud-Daulah.

What is noteworthy is the fact that the shift of capital wasn’t occasioned by the rise of nationalist sentiment. Indeed, Bengali opinion having been placated by the annulment of Curzon’s partition of the province was largely — and short-sightedly — indifferent to the issue.

In moving the capital to Delhi, the raj was consciously attempting to shift gear. As the secretary of state, Edwin Montagu, put it, the objective was to signal a break with the past and create a new British-India where “the ascetism of the Oriental, the simplicity of his code of life, and the modesty of his bodily needs, are meeting the restless spirit of progress in material things, the love of realism, the craving for the concrete and the striving towards advancement which come from the West.” Montagu even cited, with considerable approval, Rabindranath Tagore’s hope of the meeting of the East and West at “the altar of humanity”— an exercise where New Delhi would resonate with symbolism.

Secondly, in determining both the location — detached from the Civil Lines and away from the scenes of the fiercest battles of the 1857 uprising — and the design, the underlying philosophy was the evolution of the British Empire from conquest to consent and cooperation.

Lutyens, the chief architect, had built his reputation on building country houses for well-off Britons. They were built, noted a posthumous tribute in Country Life, “for people who had no particular discrimination in architecture but who were driven to recognise in his buildings the perfect embodiment of the sentiments they both cherished. In his houses Lutyens spoke… for the inarticulate upper-class Englishman”.

In India, the clients weren’t ‘inarticulate Englishmen’. In India, Lutyens encountered men who were lucid, fastidious, demanding, occasionally unbudging and who knew what they wanted. “To express modern India in stone, to represent her amazing sense of the supernatural, with its complement to profound fatalism and enduring patience, is no easy task”, he despaired.

The challenge was further complicated by Lutyens’ mental block on Indian architectural traditions, his own penchant for European classicism and the viceroy’s absolute insistence that the new capital must have a definite feel of India. It was to negotiate these conflicting impulses that Baker — relatively unknown in Britain but celebrated in South Africa — was appointed to partner Lutyens. As the historian, David Johnson, wrote in his well-researched New Delhi: The Last Imperial City, “Baker’s ability to adapt architectural style to a given location would help silence critics who worried that Lutyens, if left to his own devices, would create an architectural style totally foreign to India.”

Judging by the ferocity with which Lutyens’ legacy is being upheld by both sides in the Central Vista debate, the duo did something right. The British Empire barely endured the inauguration of New Delhi, but the imperial grandeur Lutyens set in stone has become a part of the Indian imagination.

Finally, when New Delhi was inaugurated in 1931, it boasted only a few iconic state buildings — Government House, the two imposing secretariat buildings on both sides of its approach, the circular Council building, and the War Memorial at the end of Kingsway. The rest of the city was still work in progress. It was to remain that way by the time World War II intervened and was followed by Indian Independence.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the presiding deity of Indian aesthetics in the aftermath of Independence, was at heart partial to the Le Corbusier style of modernism. He tolerated Lutyens’ mark on the landscape, but without enthusiasm. The consequences of this were profound. As the scope of the government expanded, there was a rash of new buildings to accommodate the ministries. Unfortunately, they were neither faithful to Lutyens’ style nor the philosophy behind it. In the spirit of the new socialist but impoverished India, functional necessities were combined with either post-War ugliness or modernism as viewed through the prism of the Public Works Department. The importance of stylistic harmony was largely discarded. The unfortunate Indian penchant for ad-hocism became the governing philosophy despite the formation of specialist bodies to oversee aesthetics.

Lutyens wasn’t entirely discarded: his legacy was confined to the ceremonial avenue, now Rajpath, the grand buildings on Raisina Hill, Parliament House and the façade of white bungalows with majestic lawns.

The biggest casualty was a coherent philosophy. Perhaps this was inevitable in an India that was uncertain and confused over its self-image. At the heart of New Delhi was a discarded imperial vision that hadn’t been replaced by anything tangible. Honestly speaking, this didn’t matter to an India that was still caught between conflicting political and economic pulls, not to mention going beyond survival. In today’s India defined by soaring ambition, relative institutional stability and galloping self-confidence (which will outlive the pandemic), the ‘vision thing’ is deemed important.

There will always be disagreements over the aesthetics of the ongoing Central Vista project. What matters is a larger question. Do the new buildings exude the same sense of power and majesty as what Lutyens and Baker tried to achieve? To these attributes must be added efficiency and authenticity. A century after New Delhi was created, the challenge is to embellish past grandeur with a new vision for India that is authentic, majestic, democratic but also exudes power.