The recent debate on nationalism between the two commentators, Yogendra Yadav and Suhas Palshikar, has expanded the scope of public discussions on this politically volatile and emotionally sentimental issue. Yadav makes a powerful argument that “positive nationalism”, which was the outcome of our freedom struggle, is being slowly forgotten. He asserts that socio-religious diversity was envisaged as a unique feature of India’s political existence to reject the Eurocentric nationalism of one culture, one religion and one people. This creative and essentially non-Western conception of nationalism, he claims, is being strategically overlooked. As a result, “[a]n obsession with One-Nation-One-Something replaces unity with uniformity.” Palshikar, on the other hand, reminds us that Indian nationalism was an ambitious project, which was “difficult to realize… but easy to malign”. ‘Positive nationalism’, hence, has always been under threat because its ideological rivals kept nurturing the contradictions and conflicts, which it aimed to resolve as essential obligations.

Although this debate does not exclusively look at the complex status of Muslim identity in the project of nationalism and its rivals, it certainly encourages us to explore the post-Independence Muslim imaginations of India as a nation. This ‘Muslim story’ of nationalism is not a footnote to Indian secularism; nor is it an apology to Hindutva. Instead, it is an independent, politically diversified, and intellectually vibrant position on nationalism which has not been given serious attention so far.

I take only two examples to introduce this multifaceted, post-Partition Muslim nationalism: Hamid Dalwai’s ‘humanistic nationalism’ and Syed Shahabuddin’s Muslim India. These two examples are relevant to highlight the intrinsic diversity of Muslim opinion. At the same time, they can also help us get rid of the almost outdated discussion on nationalist Muslims.

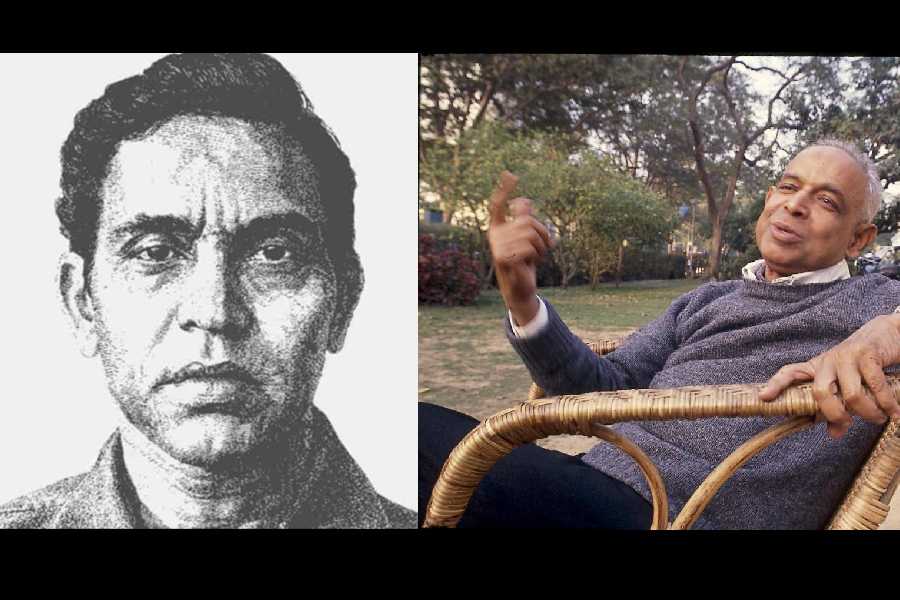

Dalwai was an activist and social reformer. He was one of the first Muslim leaders who campaigned against triple talaq and polygamy. Dalwai worked as a journalist and wrote primarily in Marathi. His book, Muslim Politics in India (1968), is, in fact, a translated version of seven Marathi articles.

Dalwai identifies the problematic role of history in producing contemporary prejudices and communal stereotypes. For him, “… history, which has bred prejudices and animosities, is a hindrance” and virtually “… all of us have to come out of the grip of our prejudices, which originate in the past” (Muslim Politics in India, p. 9). He makes it clear that “… today’s Muslim is not responsible for the oppression to which Mahmud Ghaznavi or Aurangzeb subjected the Hindus.” Dalwai calls upon communal Hindus to “free themselves of historical prejudices”.

According to Dalwai, the Muslim elite — communalists as well as nationalists — do not want Muslim communities to join the progressive, secular-modern forces. This Muslim isolationist attitude, he claims, is the main hurdle to achieving nationalism in the true sense of the term.

Dalwai offers an interesting formulation, a humanistic nationalism, to solve the problem of national unity. In the concluding essay of the book, Dalwai talks about an emerging class of modernist Muslims who do not subscribe to irrational communal ideals and prejudices. He hopes that this class of broadminded Muslims would lead the movement of progressive nationalism. He writes: “Those Hindus who want to counter Muslim communalism unfortunately try to strengthen Hindu revivalism. And those Hindus who want to lead the Hindus … on the way of modernity are unfortunately supporting Muslim communalists… A new generation of Muslims is emerging in India… One can see the first glimmers of a genuine modern humanism in them… The only answer to the communal problem… is secular integration of all peoples of India. If the question is viewed in this light… Muslim modernism would be strengthened.”

Syed Shahabuddin — a civil servant-turned-politician who played a significant role in the Babri masjid movement — offers us a different interpretation. Shahabuddin’s editorials in Muslim India, the journal he published for over two decades, are relevant to make sense of the contours of an India-specific notion of nation and nationalism from a Muslim point of view.

It is worth noting that Shahabuddin deliberately uses the term, “Muslim Indians”, instead of Indian Muslims, to justify his idea of ‘Muslim India’. He argues, “… when I say Muslim India, it is a combination of an adjunctive and a noun; my substance (noun) is India... (Thus), one aspect of India which happens to be Muslim or Islamic. I say there is a Hindu India, there is a Muslim India… there is a Brahmin India, there is a Dalit India… there are many Indias… inseparable in space, interpenetrating each other forming one great cohort” (personal interview, March 30, 2004, Delhi).

This definition of ‘Muslim India’ is based on the principle that India as a nation is essentially a plural entity. Every social and religious group contributes to this plurality and transforms it into a concrete political reality. In this sense, the idea of ‘Muslim India’ symbolises a crucial aspect of postcolonial nationalism.

Let us examine the implications of these Muslim responses to nationalism for the present debate. It is important to mention here that there is a common ground between Yogendra Yadav and Suhas Palshikar. They both seem to agree on two points: the non-European imagination of a nation (which Yadav calls “positive nationalism”) and a realistic assessment of the rival tendencies, which tend to undermine the ambitions of positive nationalism (which Palshikar emphasises strongly).

Dalwai and Shahabuddin, despite taking two very different positions, seem to recognise the non-European ‘positive nationalism’ as a political precondition. They try to expand the meanings of this ambitious project by critically engaging with legal-constitutional structures, political processes, and the changing dynamics of intercommunity relations. This nuanced intellectual-political exploration helped them offer creative reinterpretations of nationalism from their own vantage points.

Dalwai’s critical assessments of Hindu and Muslim communal elite may be seen as what Palshikar calls the “rival tendencies”. He, however, goes a step further. Instead of merely criticising the communal forces, a bold and future-oriented resolution is offered. Shahabuddin’s notion of ‘Muslim India’ has its own political value. He conceptualised this idea exactly at the time when Hindutva politics began to appropriate nationalism in the early 1980s. He evoked ‘Muslim India’ to clarify the distinction between the Hindutva project and the promises made by India-specific positive nationalism.

The present moment of Indian politics is significantly different from the time when Dalwai or Shahabuddin were active. It is, therefore, not possible to invoke the imagined promises of progressive modernism and/or assertion of ‘Muslim India’ as the ultimate answers to deal with Hindutva dominance. Dalwai and Shahabuddin, however, are not completely irrelevant. They might be treated as serious intellectual resources, which could help us construct an entirely new, non-elitist, progressively inclusive and essentially non-European imagination of Indian nationalism.

Hilal Ahmed is Professor, CSDS, New Delhi