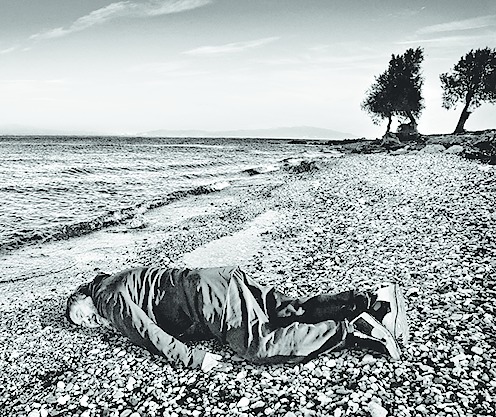

A man - he was lying face down - was recently photographed on the pebbled beach of Lesbos in Greece. He wore a crumpled black dress, and had his head twisted to left. However, he was not another Syrian migrant whose body had been washed ashore. The 'model' was Ai Weiwei, the Chinese artist, who had decided to recreate the chilling image of the drowned Syrian child, an image that continues to haunt those who have chosen to view the migrant crisis in Europe sympathetically.

But the iconography of suffering and endurance of the refugees is layered. It reflects the complexities inherent in the global response towards the men, women and children who have perished in , or have survived, the perilous voyage to the continent from the troubled Middle East. Ai's engagement with the refugees is, in his words, an attempt to "not just... watch events but to act." His critics, not all of them are from China, have accused him of cleverly blurring the lines between commerce and conscience. A counter-narrative, in the form of image and text, has also emerged challenging Ai's views across traditional as well as digital social media platforms. What informs these representations is the unconcealed animosity towards the migrants. A video, showing an European man being assaulted by refugees inside a train compartment, had recently gone viral on Facebook. The victim, we are told, had protested after witnessing his assailants teasing a woman passenger. What we are shown are stills of an elderly, cowering man surrounded by a group of young men with distinct Middle-eastern looks. In Cologne and Stockholm, European women were reported to have been sexually assaulted by refugees who encircled them in public spaces. Such a strategy, The Independent declared, may have been connected to the notorious taharrush gamea, a form of group harassment, that has shamed Egypt.

Europe's right-wing discourse has exploited these thinly-veiled references for political gain. It should remain grateful to the imagery - videos, photographs, sources of which remain vague - and their textual inferences that have been instrumental in consolidating the fear of being besieged among host European nations. The panic is not just about sharing scarce economic resources with claimants from a different, and demonized, faith. Europe's fear, in the eyes of commentators and citizens, is deeper and primordial - it is the fear of chaos and contamination.

Yet another series of photographs conveys this anxiety quite effectively. These images depict an unruly people - a turbulent sea of hungry, starving faces - crowding around impassive border guards standing in neat files

Representation - accurate or of the twisted kind - has to contend with the politics of effacement. This remains true of the imagery of the migrants. Compared to the vast number of photographs of refugees on water or on land - fragile rafts battling the grim Aegean Sea or people being herded across checkpoints -there is sparse documentation of the lives of those who have found shelter. The invisibility of the rehabilitated refuge is a telling comment on Europe's claim of being a famed melting pot. Denmark, Poland and Hungary, nations that have refused to accommodate migrants, have been accused of being indifferent to the values - fraternity, equality and humanism - that were once synonymous with the idea of Europe itself. But after Cologne, even benevolent Germany appears keen to shield the migrants from the searching gaze.

Visual narratives of displacement need not be inclusive. Ai Weiwei may have resurrected the Syrian child in public consciousness. But Vietnam's Boat People or Myanmar's Rohingyas are yet to find a patron in the Arts.