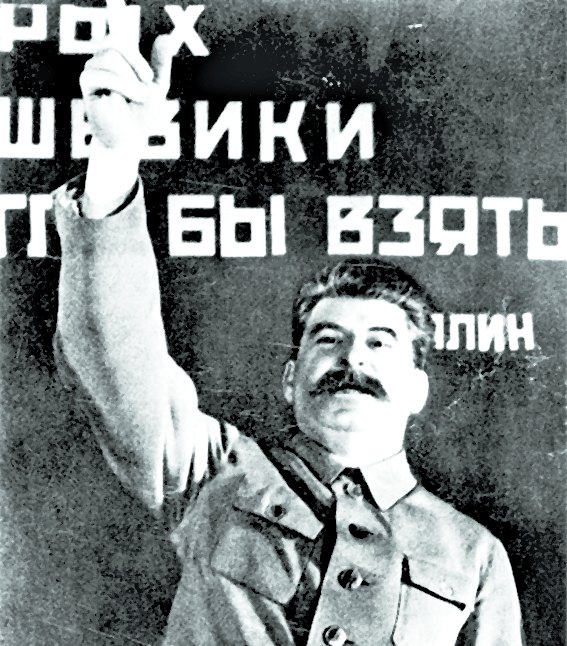

STALIN: Volume I Paradoxes of Power, 1878-1928By Stephen Kotkin, Allen Lane, $40

This mighty work of scholarly endeavour is a monument cast in the finest stone. Sir Stafford Cripps, an eminent British Labour politician and wartime ambassador in Moscow described the Soviet leader Iosif Stalin as 'one of the greatest men of all time, judged by the immensity of the changes he has brought about in the largest country in the world,' a sentiment refined with critical acumen by Stephen Kotkin, Professor of Russian History at Princeton University, who has embarked on the massive enterprise of writing a comprehensive biography of the man and his times in three volumes, of which this 948-page tome is the first. Meticulously researched in Russian archives, leavened with a wealth of secondary texts, its narrative power and historical sweep propel the author into an orbit of solitary eminence.

The geography of Russia's Tsarist empire sprawled across 11 time zones: not wholly of Europe, nor of Asia, but Eurasian: more a world than a State. The empire's landscape included diverse communities: Russians, kindred Slavs, Tatars, Mongols and numerous other ethnicities , with their Eastern Orthodox and Lutheran churches, Roman Catholic cathedrals, Muslim mosques, Buddhist temples and Shaman totems as sanctities.

'If Stalin had died in childhood or youth, that would not have stopped a world war, revolution, chaos, and likely some form of authoritarian redux in post-Romanov Russia,' writes Kotkin. 'And yet the determination of this young man of humble origins to make something of himself, his cunning, his honing of organizational talents would help transform the entire structural landscape of the early Bolshevik revolution from 1917... Then he launched and saw through a bloody socialist remaking of the entire former empire, presided over a victory in the greatest war in human history, and took the Soviet Union to the epicenter of global affairs. More than any other historical figure, even Gandhi or Churchill, a biography of Stalin... eventually comes to approximate a history of the world.'

Born in December 1878 in Gori to illiterate former serfs - his father, Vissarion, was a cobbler, his mother, Ekterina, a washerwoman and seamstress . Gori, a Georgian market and artisan town was populated also by Russians, Armenians, Persians and Turks. Iosif Vissarionovich Jughashvilli was the couple's only offspring to survive the complications of child birth. He was the diminutive Soso to his mother and boyhood friends, then Koba (Turkish for indomitable) in early manhood; finally, in 1913, the more stately Russian, Stalin, Man of Steel. Young Iosif excelled at school, learning Church Slavonic and Greek (in which he tackled Plato); he read out the liturgy and sang the hymns. He was awarded David's Book of Psalms with the inscription: 'To Iosif Jughashvilli... for excellent recitation of the Psalter.' Next came the theological seminary at Tiflis, where he trained for the priesthood but was expelled for insubordination. Stalin was a voracious reader, an autodidact with a phenomenal memory, striving always to improve himself. A precocious, published poet in Georgian at the tender age of 17, he spoke the language in its purest form and acquired a flawless command of Russian, tinged with a noticeable Georgian accent. He revelled in the works of Russia's greatest writers, Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Turgenev, Chekov; and was uplifted by Russian classical music, ballet and opera. Russian and Georgian folksongs were an inebriating inspiration. His nemesis Leon Trotsky's claim that Stalin was a poorly educated Asiatic apparatchik may be ascribed to the malignity of disappointed humanity.

Kotkin's textured blend of biography and history, the latter brought into play at critical moments of Stalin's career, is deftly accomplished. The crisis of empire, its unbending autocracy, its overarching secret police, failing civic institutions and an increasingly restive intelligentsia, Russia's ill-starred war with Japan in 1904-05 set the scene for the denouement of October 1917. The Interior Minister Pyotr Durnovo issued a dire warning to Tsar Nicholas II in a Memorandum dated February 1914 on the possible perilous consequences of a war with the Kaiser's Germany. 'The trouble will start with the blaming of the government for all disasters ... a bitter campaign against the government will begin, followed by revolutionary agitation throughout the country, with socialist slogans, capable of arousing and rallying the masses, beginning with the division of land and succeeded by a division of all valuables and property. The defeated army, having lost its most dependable men, and carried away by the primitive peasant desire for land, will find itself too demoralized to be a bulwark of law and order. The legislative institutions and the intellectual opposition...will be powerless to stem the popular tide, aroused by themselves.'

The prescient prediction proved uncannily true. The First World War broke out in late July 1914. Nicolas II abdicated in February 1917. The end came with the fall of Alexander Kerensky's regime, leaving the field open for the revolutionary Soviets of soldiers and workers. Sizing up the situation, Lenin called for the immediate seizure of power by the Bolsheviks. Land, bread and peace was their electrifying call to arms. Kotkin takes us through the regime's early Time of Trouble, from the civil war, the military intervention of foreign powers, led by Britain and America, famine, the fiasco of the Russo-Polish war, and the unilateral Brest Litovsk peace with Germany. As one would expect of a mainstream American writer, Kotkin is censorious about Lenin and the Bolshevik assumption of power, and its supposedly damning political and economic consequences. More startling is his view that Lenin's typed Testament asking for the removal of Stalin as General Secretary of the Communist Party lacked authenticity. He was struck by the absence of a stenographer's copy in the Russian archives. Since the document was dictated by an incapacitated Lenin there must surely have been one. None was to be found. It was unlikely, says Kotkin that Lenin would want Stalin deposed within a year or so of appointing him to the post.

Be that as it may, the Testament was a sword of Damocles over Stalin's head. It could have led to his early dismissal, but he surmounted the machinations of his rivals Grigori Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, emerging stronger for the ordeal. Kotkin quotes extensively from the original transcripts of the Stalin-Trotsky head-to-head confrontation at the 14th Congress of the Communist Party in December 1927 - a bruising encounter in which no quarter was given, and none expected. The communist debacle in China, in April 1927, was the dispute; Stalin's supposed indulgence towards Chiang Kai-shek came under fire. 'You are the grave digger of the revolution,' shouted Trotsky, as Stalin walked out of the hall in high dudgeon. The immovable object withstood the barbs of the irresistible force: 'Stalin's abilities and resolve were an order of magnitude greater,' than that of Trotsky, writes Kotkin, whose concluding pages are devoted to Stalin's break with Nikolai Bukharin over the party's New Economic Policy, which prioritized peasant interests. Stalin, unlike Bukharin, was prepared to switch gears and move towards faster economic development involving crash course industrialization. Only a strong industrial base would guarantee the country's ability to repel foreign aggression. Collectivization of agriculture was Stalin's great gamble, says the author. The resulting upheaval and political destabilization made many insiders quail. 'Stalin did not flinch...he would keep going...full speed ahead to socialism. This required extraordinary maneuvering, browbeating, and violence on his part. But he had will. History, for better or for worse, is made by those who never give up.'

Within a decade, the Soviet Union had been transformed into the world's second industrial power after the United States, equipped for the titanic struggle to come with Nazi Germany.