In the summer of 1974, amidst a deepening economic downturn, an increasingly authoritarian Central government faced off against striking railway workers. The 20-day railway strike, led by George Fernandes, would help fortify an anti-government sentiment that was already gathering pace with the JP movement, which would eventually lead to the undoing of the powerful Indira Gandhi government.

It is tempting to hear the echoes of that turbulent summer in the winter of 2020 when lakhs of farmers have encircled the national capital for over three weeks. This is also perhaps the first time in five years that the government has found itself on the back foot politically, its dazed response veering between conciliation and condemnation. However, unlike the pre-Emergency protests that roiled India, these protests are not potent enough to pose a fundamental threat to the popularity of this government.

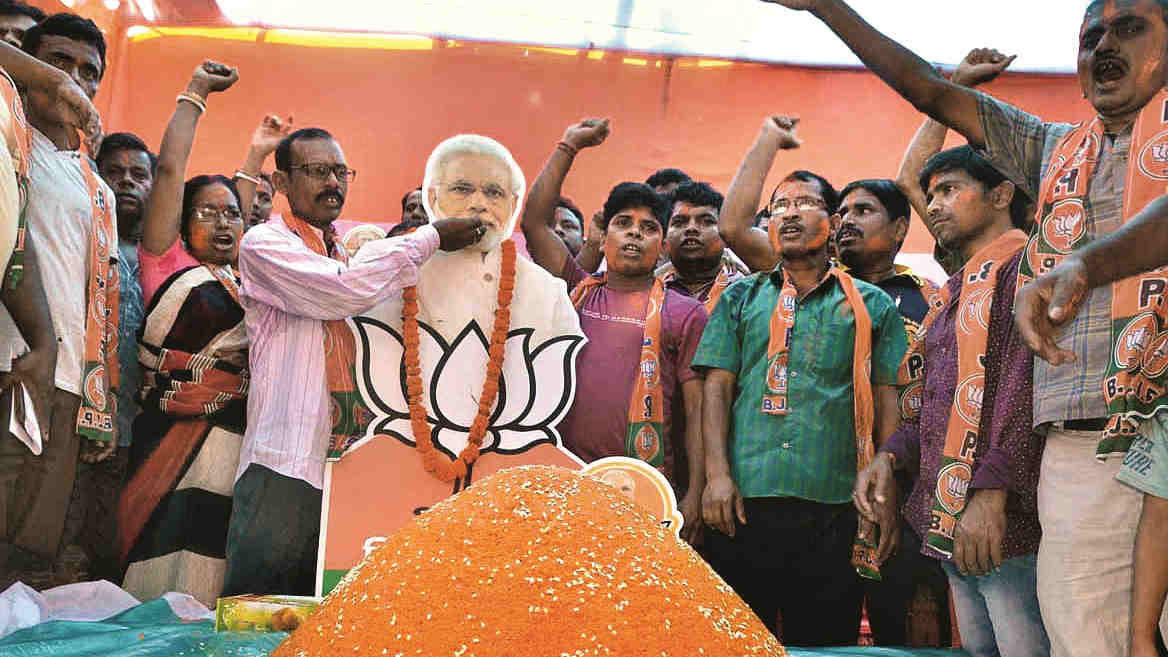

This is because these protests have neither the leadership nor the vision to challenge the ideological hegemony of the government — the basis of its political dominance. This is a self-contained, civil society-led movement with limited demands. As the recent local body polls in rural Rajasthan indicated, there isn’t any evidence to suggest that these protests have the potential to shake up popular support for the Bharatiya Janata Party.

However, much like we saw with the protests against CAA-NRC last winter, such protests can spark a certain romantic imagination of an alternative idea of India bubbling up from below. A giddy expectation that the masses will lead us to the promised land; a distilled political vision emanating from the enchanting confection of songs, slogans and placards. But a political vision only comes from a political leadership. Without leadership, the immense energy generated by civil society-led protests would, sooner or later, dissipate into the footnotes of history. To make history, you need a leadership expounding a vision and an organization to carry it through. In other words, you need a political movement.

Both the anti-CAA-NRC and the farmers’ movement have been similar in two respects. One, its guiding impulse has not been politics but an apolitical idealism, consciously eschewing the support of political parties. Two, in place of a clear leadership, both protests have been led by a dizzying array of civil society actors with differing conceptions of the objectives of the movement.

The success of the JP movement was premised on exactly the opposite — a political vision (‘Total Revolution’) that brought Opposition political parties together on a common platform, and the towering leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, which connected disparate student movements in Gujarat and Bihar, melded it with the grievances of farmers and workers, thereby expanding it into a national movement. It must be noted that an uplifting political vision does not mean an exact political programme. JP’s ‘Total Revolution’ — a mix of democratic decentralization and corruption-free governance — was vague enough to attract a broad swathe of the population while being inspiring enough to energize people into anti-government action.

Unlike the present farmer leaders, Fernandes, who led the railway strike, was a militantly anti-government political actor who enthusiastically supported the JP movement and unabashedly linked the strike to the destruction of the government. In March 1974, Fernandes had remarked that “railwaymen could unseat the present Central Government through a general strike.” Similarly, whereas the Gujarat student movement was largely apolitical, the Bihar student movement was led by budding political leaders linked to the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the Socialist Party and the Lok Dal. This was the reason the Bihar movement became a breeding ground for a generation of politicians who would dominate Bihar in the coming decades. Even though Jayaprakash Narayan did project an ‘above politics’ image, he openly courted the support of the political parties. They included the Jana Sangh, whose annual meeting he addressed, and the RSS, whose cadre formed the organizational core of the JP movement.

The limited political horizons of the farmer protest can be gauged from the fact that almost all other protesting farmer unions promptly distanced themselves from the Bharatiya Kisan Union (Ekta-Ugrahan), which organized demonstrations for the release of political prisoners. Joginder Ugrahan is perhaps the only major farmer leader with an alternative political vision, who has clearly linked the woes of the farmers to the shrinking space for democratic freedoms. The anti-CAA protests, although they were more forthright in their ideological challenge to the government, were largely unsuccessful in expanding beyond minority-dominated spaces and, hence, at no point did they threaten the political calculations of the government. In both cases, the protests remained confined to their particular constituencies because of an absence of leadership. While the predilection of activists is always to cater to their base, only a political leadership has the will and the capacity to forge coalitions of distinct constituencies on the basis of shared goals.

This is why any hope that the challenge to the BJP might come from outside the established political parties needs to be tempered with a heavy dose of reality. We have seen civil society protests for much of the last few years, but unlike the pre-Emergency protests, these protests have not given birth to any genuine mass leader. Civil society protests have their place, and are no doubt inspiring in many ways, but they can’t take the space of the political Opposition.

This brings us to the incompetence of Opposition political parties, which have singularly failed to capitalize on the government’s failures and the resulting undercurrent of resentment, and have ceded this space to civil society organizations. One part of the reason students, minorities and farmers have hit the streets at various times is that they have little faith in the effectiveness of Opposition parties to push through their concerns.

Most of the Opposition parties have acquiesced to the larger ideological framework of the BJP, and are too timid to mount a forthright ideological challenge. These recurring protests are an outcome of the contradictions present in the BJP’s system of dominance; yet there is no political leader, like Jayaprakash Narayan, who has the skill, imagination and credibility to convincingly articulate how these contradictions tie into each other, formulate an alternative political vision, and build a sustained political movement based on it. Until we have such a political leadership, the BJP might lose a few battles of public opinion but will keep winning the war.

The author is a political columnist and research associate with the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi