Last month, The Conversation wrote about the self-censorship that has set in the United States of America since the Donald Trump administration took charge. What it described was reminiscent of what Indians have experienced over the last decade and more. Growing polarisation leads to self-censorship. So we now have the bizarre spectacle of the US following in India’s footsteps.

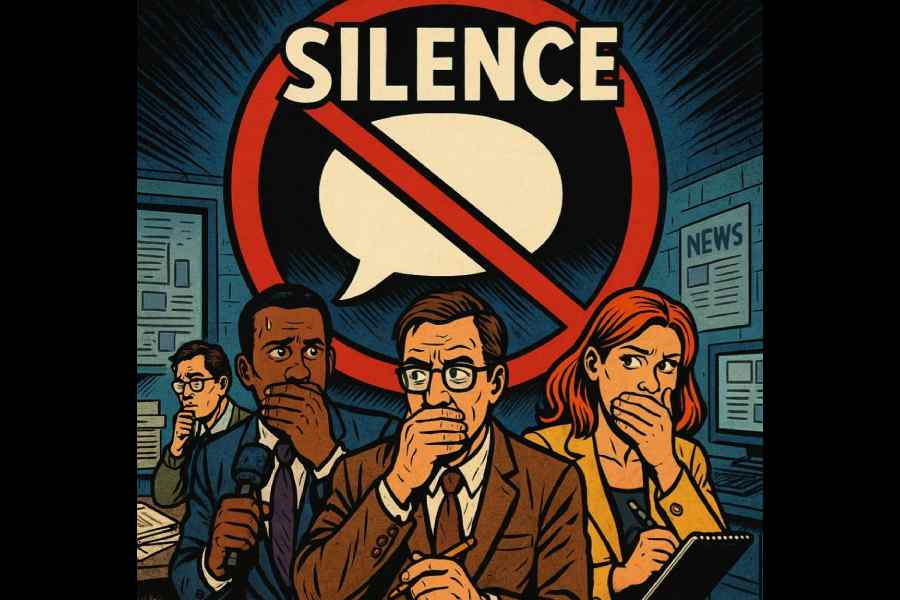

The site said that about three to four times more Americans said that they did not feel free to express themselves, compared with the number of those who said so during the McCarthy era. It said that the self-censorship we are seeing has been theorised as a ‘spiral of silence’ by the German political scientist, Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, in the 1970s in her research on public opinion. It is the title of a book that examines public opinion as a form of social control in which individuals shape their behaviour to fit prevailing attitudes about what is acceptable. The ‘spiral of silence’ is triggered when those expressing views publicly on a controversial issue are criticised or attacked by an aggressive minority.

Self-censorship is described here as listeners or readers imposing costs on a speaker or writer. But a long-term consequence of this is that if you do not express a view, others who hold similar views will not know that there are others like them; they will think they are in a minority, whereas they could be the majority. The opinions of the aggressive minority then become dominant. True public opinion and expressed public opinion diverge.

The Conversation is a website which draws upon academia to bring depth to its treatment of contemporary issues. A podcast published in the same month discussed a growing frenzy of self-censorship among academics in the US. “Shortly after the new US administration was established, we started getting calls. From scholars who have written for us. ‘I don’t want my name attached to that.’ So many such calls. It became a clear trend. ‘Hey, can you take that story down/ can you remove the funding statement from my disclosure?’ We said no we don’t do that. Others would be close to finishing a story on immigration or abortion care and then they would say I don’t think this is the right time to publish this.”

The podcast said that a couple of private universities were scrubbing the words, diversity, equity and inclusion, from their websites, along with mentions of climate change. They were doing it as an act of self-preservation. They did it to protect their mission because they got research grants from the federal government. The podcast clarified that it was speaking about a minority of scholars and universities.

But what was the alternative, it wondered. Do you use the word, pluralism, instead of DEI? Do you stop using the term, climate change? The host talked to Daniel Bar-Tal, a professor at Tel Aviv University in Israel, on how the Israeli government uses censorship and self-censorship to prolong the conflict. “The journalist take position of writing in self censorship. Public expects journalists to self censor. Don’t talk of numbers of those killed. To satisfy the public. Not report what is going on in Gaza, or in Palestine society.” As for himself, he has been singled out by the Israeli Academic Monitor for the research he does. “Societies that are involved in intractable conflict have certain monitors,” he said.

Academics are under scrutiny in India as well. When Ashoka University’s professor, Ali Khan Mahmudabad, finds the highest court of the land ruling that a special investigation team, no less, will examine his social media posts following Operation Sindoor, it follows that other academics and civil society denizens will begin to think twice before they express their views.

Growing self-censorship in India has been widely documented. The French journalist, Vanessa Dougnac, was forced to leave India in February 2024, having earlier been stripped of her work permit in September 2022. Her departure followed the cancellation of her Overseas Citizen of India card. (In March this year, the Union ministry of home affairs informed her that she had been given a one-year work permit.)

Around that time, Reporters Sans Frontières documented that more and more foreign reporters in India had begun to steer clear of sensitive subjects for fear of losing their residence permits. It added that journalists of Indian origin living abroad had stopped covering India in order to be able to keep visiting as tourists.

The rise in self-censorship in the Indian press is on account of the dominant political leadership. There was an extraordinary demonstration of this earlier this month when the local press played down the house arrest of the chief minister, cabinet ministers and politicians in Kashmir on July 13, commemorated as Martyrs’ Day. The lieutenant-governor’s administration wanted to prevent them from visiting the martyrs’ graveyard, but the good chief minister scaled a wall to get there. But it was not a front-page story for the local press the next morning, some even skipped covering it.

The best counter to self-censorship is competition and multiplicity of media. While most Indian media outlets did not go beyond reporting the official death toll in the crush of pilgrims at the Kumbh Mela on January 29, Indian reporters for BBC News gathered testimonies from across India to reveal, months later, that 45 more deaths had occurred.

But conversely, when the BBC chose not to air a horrific film showing the targeting, detainment and torture of medics in Gaza called Doctors Under Attack, it aired on Channel 4.

The truth will out.

Sevanti Ninan is a media commentator. She also publishes the labour newsletter, Worker Web