Lalu Prosad Shaw's graphic art and temperas could not have been more dissimilar, but they do have something in common. Both are meticulously executed, and are outstanding not only for their technical perfection but also for their balance and harmony. As CIMA Gallery's ongoing exhibition of the works of the Birbhum-born artist, who is approaching 80, proves, Shaw can still handle a pencil and brush with dexterity. The exhibition's title, Babus & Bibis, makes clear that Shaw's focus is still on the supposedly laidback years of the late 19th century, when middle-class folk could afford the luxury of post-prandial siestas, and one could also choose daydreaming as one's favourite occupation.

The artist denies his paintings and graphics are contradictory to each other, for in both he deals with form and space. The focus of his paintings is on a single figure, and in his graphics he projects form on a surface. His graphics were his response to the machinery that lay scattered around the hardware shops of Thanthania in north Calcutta where he lived in his early days of penury.

Yet, however relaxed the protagonists of his paintings may seem to be, they hold stiff and rigid poses, as if they were inside a studio in front of those large and cumbersome cameras, waiting for the photographer, who was hidden under a piece of black cloth, to replace the lens cap. They could be the subjects of photographs Shaw used to see displayed outside a studio tent at melas in Suri, where he was born and raised.

Two young men in dhoti and pyjama, respectively, are on the floor, one of them with a palm leaf fan in his hand. He could doze off any moment. The other man stares either at the ceiling or the sky, engrossed in his thoughts. As in Indian miniatures, there is no attempt to suggest light and shade as his colours are flat, with rhythmic lines indicating form and mass. Another young man in a dhoti and kurta stands with a flower near his nose. His limbs are so frozen a butterfly has settled on the bloom. The man in a light cream kurta, indicating silk or tussore, stands out against the dark red backdrop.

The women, like the men, are painted mostly in profile, once again linking Shaw with miniature traditions. In the case of women, Shaw uses colour liberally, but mostly solid shades such as green, blue, red and yellow. These saris have bright, contrasting borders, or they are either chequered or striped creating an illusion of fluidity and curvaceousness. Shaw goes in, in a big way, for contrasting shades that enhance the illusion of mass.

His protagonists - both male and female - are doe-eyed, and have straight noses and full, sensuous mouths. Even the loose woman holding up her arms to reveal her rounded breasts shares these facial features. One of his most striking line drawings is that of a woman with a sari draped loosely around her frame, Kalighat pat style. The economy of this composition and the clarity of his unfaltering line are quite remarkable. But then Shaw's line drawings are remarkable.

Shaw's two-dimensional figures as in pats have evolved from his deep interest in the Bengal School and media like watercolour (washes in particular) and tempera. Journals such as Bharatbarsha and Probasi had exposed him to masters like Gaganendranath, Abanindranath and Nandalal Bose, and in later life they became his inspiration.

Ramananda Banerjee often paints images similar to those of Shaw's, but the former loves the decorative. Men and women in dhotis and saris were regular features in Dharmanarayan Dasgupta's paintings, too, but his flying figures, à la Chagall, were clearly holding to ridicule Bengali middle-class mores and repressed sexuality. Shaw's humour is devoid of the barbs of satire. It is of a gentler, innocuous variety, often with a touch of surrealism and suggestions of eroticism. The decapitated head of a man wears a balaclava, a favourite headgear of Bengalis of a certain age. A disembodied hand holds a vase. The decapitated head of a woman is displayed on a column. But her mouth is so ripe a butterfly hovers around it.

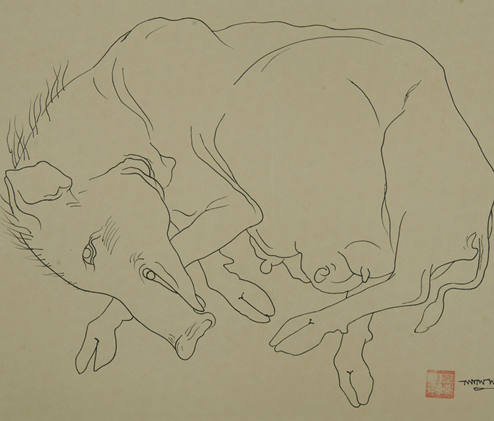

These are images he has displayed repeatedly, albeit with subtle variations. A painting has turned into a line drawing, or vice versa, or else he has gone back to the same theme with crayon. Some of his best drawings were inspired by his Santiniketan sketchbook. The ponderous sow with her teats almost touching the ground has a contented look as she curls up to sleep.