Though not a ‘leap year February’, it is February and I recall two notable Indians who were born on the last day of February.

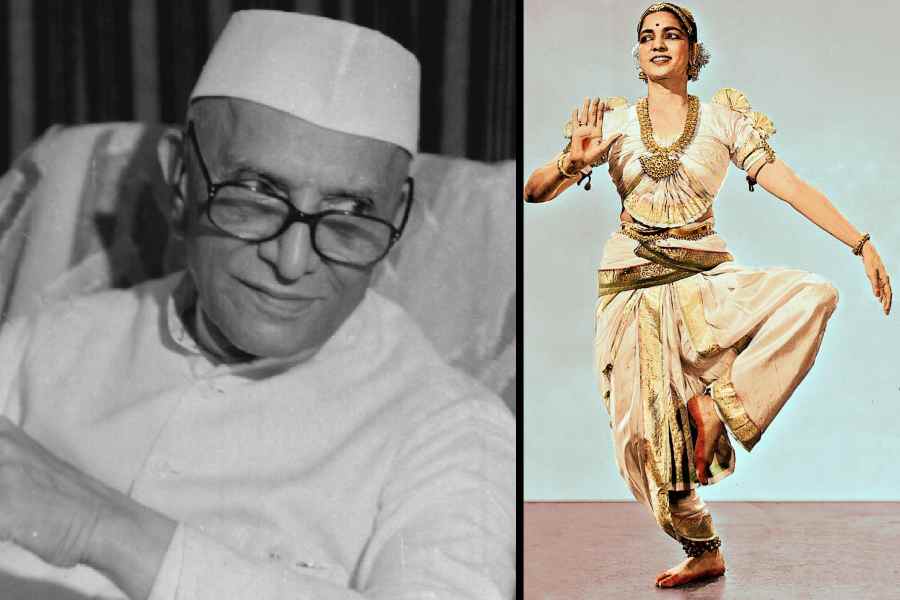

Morarji Desai arrived in the modest Gujarati home of a school teacher in a village in Bombay Presidency’s Bulsar district, on February 29, 1896.

Rukmini Devi was born in the similarly modest home of a PWD engineer in Madras Presidency’s Madurai, on February 29, 1904.

That made them leaplings — an unlovely word which sounds like weaklings. Or leapers, which sounds even worse.

But are leaplings or leapers supposed to have much in common apart from being privileged to mark their birthdays only once in four years? Rationalists would say “Blah!” to that question. Others might ponder it.

Those two were markedly different.

Morarji knew no Tamil, Rukmini’s Hindi was basic.

His big ears did not catch music, his large eyes did not behold dance.

For her, the arts were life. Music and dance infused not just her life, but life itself.

He quit the provincial civil service for politics.

She was wholly apolitical.

If ever romance touched Morarji Desai’s life, only he knew about it. But Rukmini Devi’s teenage love for George Arundale, her senior by twenty-six years, was well-known. Her father and George were both Theosophists and never did that esoteric faith bloom in love as it did with this Tamil lass and English gent.

Morarji was conservative. His mind censored. Rukmini was conservative too, but her mind did not censor; it edited. There is a difference.

In all this, these two leapers were very different.

And yet their stars could leap onto the same page.

Morarji Desai was vegetarian.

Rukmini Devi was, too.

Morarji Desai wore homespun khadi, but unlike some khadi-wearers he did not look crumpled like yesterday’s newspaper. His dhoti and kurta dazzled in white.

Rukmini Devi wore handweaves but never looked like the bandaged survivor of a road hit. Her six yards of handloom had art; her saris spoke of and sang taste.

In his appearance he was never slack, she never slatternly.

Some major characteristics too they shared: they were hugely opinionated. And how! They would not budge from their positions. More, they propagated their positions, one with hauteur, the other in high style.

Neither drank. Both looked down on those that did. As one might on someone who lied, or beat his wife, or stole from a blind beggar’s bowl.

The word, ‘drink’, in the context of Morarji Desai occasioned in shallow minds recollection of his belief in auto-urine therapy. The idea appalled me then and does even now but the impulse behind those who sniggered at Morarji Desai was facetious. Ignoring the fact that the practice is part of the world of alternative medicine with thousands of adherents across the globe, one particularly cynical friend of mine went on about Morarji “drinking his own urine”. After a point, I had to plagiarise Abraham Lincoln and ask him, “Well whose urine do you want him to drink…Yours?”

In the matter of food, Morarji was a faddist while Rukmini was, I would say, fastidious. He had to have his blanched almonds, his carrot juice. She her salads and no, oh no, eggs anywhere on the table.

Courtesy family ties, I knew both of them and admired them hugely. And they were both most kind to me. As a kid at school (Modern School, Barakhamba Road, New Delhi), I was able to get him to come as chief guest at my House Day event, a minor occasion. He was the country’s finance minister at the time and yet made the time. He arrived “on the dot”. Our programme was slow to start. He waited patiently, did his bit by way of distributing prizes, making a speech, but while leaving gave me in crisp Gujarati a verbal hiding I have never forgotten for taking others’ time for granted. But the anger was momentary. Some years later, I requested him to come to my college (St. Stephen’s College, Delhi) and address us undergraduates. He came, spoke briefly, and offered to take questions. Predictably, he was asked by a bright seventeen something: “Sir, do you drink?”

“No, I do not.”

“Why?”

“It is a bad thing to drink.”

“If you don’t drink, how do you know it is a bad thing?”

The questioner-cum-heckler drew claps. Not very loud, but fairly strong.

“I do not have to pour Prussic acid on my hand to know it will burn my skin.”

Morarji’s answer drew a bigger applause than the jibe had. Was I relieved!

Rukmini Devi was our house guest in Kandy, Sri Lanka, where I was posted in the early 1980s. Another dear friend was also staying with us. It was standard for us to have eggs at breakfast time. My wife said, “Look, she will be uncomfortable… We can dispense with our omelettes and stuff while she is with us at the table.” Crass ego made me say, “No, why? One guest is as valued as the other. He would like his eggs and so would I. She has to adjust.” Rukmini Devi’s eyes widened as she saw the yellow discs appear on the table along with the idlis and the dosais she liked.

RD: “I did not know you ate eggs.”

GG: “Well, yes…”

RD: “I see… So… is that for your health…?”

GG: “No… Actually I quite like them.”

RD: “I see… You like them… But must you have them…?”

I could have heard the fried eggs start to fly and chirrup.

She told us then of how once standing at the platform of the railway station in Madras for her train, she felt the pallu of her sari being pulled. She turned to see what was happening to find that a monkey in a cage was pulling at the cloth to draw her attention. There were other monkeys in the cage as well, all waiting to be carted to some place from where they would be exported for medical experimentation. She decided then and there to move to have the thing stopped. A nominated member of the Rajya Sabha at the time, the very first woman to be so nominated, Rukmini Devi introduced a private member’s bill for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. So persuasive was her draft that Prime Minister Nehru had it converted into an official bill, which was passed easily, establishing the Animal Welfare Board, with Rukmini Devi, then renowned as a great dancer in the Bharatanatyam tradition and founder of Kalakshetra, as the Board’s first head.

I knew that in 1977, she had said “no” to the suggestion by Prime Minister Desai that she be the ruling alliance’s candidate for the office of president of India. But I wanted to know the full story. “Why?” I asked. “I would have been miserable in that place… men with guns all around me… and I obliged to walk shod in slippers rather than barefoot as I am in Kalakshetra… and then the need to offer my foreign guests meat…”

I knew this was what greatness is about.

But what a loss to India that “no” was!

Morarji Desai’s out-of-the-box move would have given India not just its first woman president but an outstanding personality at that.

And the world would have seen in India’s first residence, art being honoured, integrity celebrated. And India would have had, till at least 1982, a president who would have kept crass, manipulative politics at bay, the dignity of classical dance, the purity of handicrafts and the compassion of a humanist flying the nation’s flag.

And what a leap that would have been for India’s democracy.