The State is, under ordinary circumstances, an amorphous, distant entity for the privileged Indian. This is because privileges — an education, economic heft, caste and gender identities and their resultant social leverages — serve as a protective barrier, shielding such citizens from the State’s egregious policies. Thus, this numerically insignificant constituency, ironically with capacities to amplify their opinions disproportionate to their representation, usually experiences the presence of the State by proxy — through the discrimination against and the despair of others as well as of those Othered.

But there can be occasions when the State knocks — rather roughly — on the barricaded doors of the entitled. This takes place, more often than not, in the course of the implementation of government policies or mandatory bureaucratic exercises that target citizens — disadvantaged or otherwise — uniformly. Indira Gandhi’s unexpected, infamous Emergency and Narendra Modi’s equally abrupt and disruptive demonetisation can be cited as examples of the former, while the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls, unfolding at this very moment in Bengal under the watch of the Election Commission of India, is an instance of the latter.

The citizens’ close encounters with the State can appear, from one perspective, to be salutary. They, in theory, uphold one of the fundamental tenets of the democratic compact: that the State’s presence and interventions in the lives of citizens, all citizens, ought to be even: none, again in theory, is too privileged or, conversely, too poor

to evade the State’s reach. This tryst with the State should have ideally led to the crystallisation of a collective solidarity on account of the fact that the people’s experience of the State and its whims is shared.

But all this holds good only on paper. In reality, our encounters with the State are demonstrably uneven, their rough edges hewn precisely by our location on the social pyramid, which, in turn, is shaped by our privileges. The resultant moral dilemmas, however fleeting, that the engagements with the State lay bare for the privileged are seldom discussed; but they are illustrative and demand closer introspection.

Consider how the SIR played out in the life — especially the inner life — of this columnist. My resources, literacy, including digital literacy, and awareness as well as my ability to access knowledgeable people — bureaucrats, block level officers, local political representatives — by virtue of my occupation had left me reasonably confident of finding a way through the Minotaurian maze that is the 2002 electoral roll. What I was unprepared for, and this emerged only in hindsight, was the moral test that accompanied the SIR.

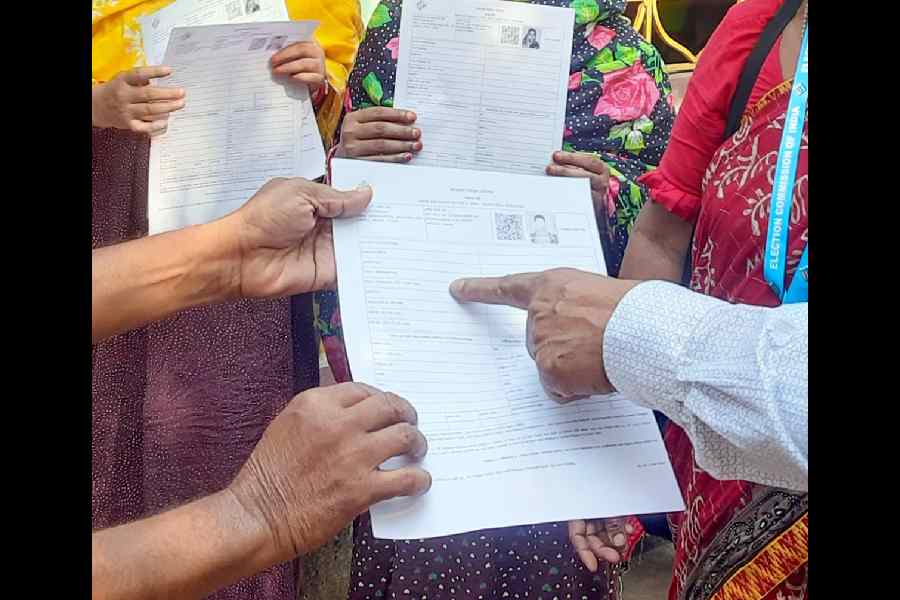

Unsurprisingly, my initial exposure to the SIR was vicarious. In early November, a few days after the exercise began in Bengal, two anxious, elderly women, both household helps for years, confided that none of them could find their names or those of their parents on the 2002 electoral rolls because neither of them had the means — reliable internet connectivity, digital aptitude, helpful friends or relatives and, most tellingly, time (their work hours are erratic and demanding) — to negotiate the process that was being demanded of them. I gave them, what I thought was, helpful advice without pausing to realise that my solution to their crisis had been based on an unconscious assumption that their economic assets and social advantages mirrored mine.

What was most revealing though was what followed.

My subliminal anxiety regarding my electoral fate had been triggered by the prospect of the exclusion of these two women on the margins. This led to a flurry of frantic calls on my behalf to some people: the BLO, a young, tired teacher, exhausted by her workload — Bengal has been witnessing BLOs committing suicide on account of their workload — appeared the very next day and the formalities were completed with lightning speed. As soon as I was assured that I now seemingly had what it would take for me to be in the rolls, my concern for those two women — old, unlettered, and vulnerable socially and economically — receded, leaving a void that was filled, in the course of the next few days, by a sympathy that was, I suspected, patronising. I still enquired whether they had managed to find a way into the digital maze that is the 2002 online electoral roll and, hence, out of the crisis but I did so from a distance, a pedestal, with the full knowledge that my future as an elector had, in all probability, been assured.

The popularity of the phrase, ‘the personal is political’, is attributed to an eponymous essay published by Carol Hanisch in 1969. Even though Hanisch denied being the original author of this phrase, it became a touchstone for radical feminism and the civil rights movement with its emphasis on identifying the threads that link the political with the personal. This deciphering, Hanisch and her peers argued, was central to creating that elusive glue called social solidarity. It is true that the linkages between the political and the personal, between the State and its subjects, have, on occasion, in the republic’s history, led to unprecedented mobilisations. Despite its divisions along the lines of caste, religion and feudalism, colonised India, even though it was nascent — untested — in terms of a political, geographical entity in the modern sense, had risen to dismantle an Empire after suffering, collectively, the talons of an imperial State. Yet, after Independence, public engagements with the omnipresent yet nebulous State have also been marked by the rupture of amity, personal and communitarian, thereby giving the State an opportunity to fracture the fraternity of citizens who, in command of unequal resources, are made to compete for what should ideally be a universal right, the right of the commons. This results in occasional intersections of the State and the people — SIR, demonetisation and so on — consolidating, weaponising, baser human instincts: competition, survival, individual triumph and so on, eroding the potential of citizens to demand aggregate relief.

The psychological ramifications of the SIR are not to be undermined. This is not only because the SIR’s hasty, bungling, insensitive implementation has resulted in mass anxiety, even death. It is also because the SIR is a barometer to assess the inner moral universe of Indian citizens not just in terms of their empathy and compassion for those threatened with disenfranchisement but their willingness to demand reparation for the latter.

I cannot be certain that I passed the SIR’s moral test.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in