International conflicts are no longer isolated events. In this digital age, images of warfare are continuously being scrolled through, shared, and talked about. This begs the question: in what ways do our perception of human existence and our obligations in politics change when conflict is merely another form of entertainment?

Theodor W. Adorno had argued that the commodification of culture within a capitalist system leads to the mass production of cultural products that are transformed into commodities, moulding individual desires and beliefs so that they align with the interests of the powerful while dulling the consumers’ ability to engage in critical thought.

The media not only entertain us but also condition us to accept prevailing societal norms. While we may believe we have unique and varied perspectives, this is an illusion that Adorno called “pseudo-individualism”. Our preference for one cultural trend notwithstanding, we are essentially following a narrative developed by unseen forces and hidden algorithms. Even more alarming is the industry’s ability to create what Adorno calls “false needs” — behind the enticing images and the continuous feed is a system designed not to liberate us but to keep us comfortably, silently, and perpetually compliant.

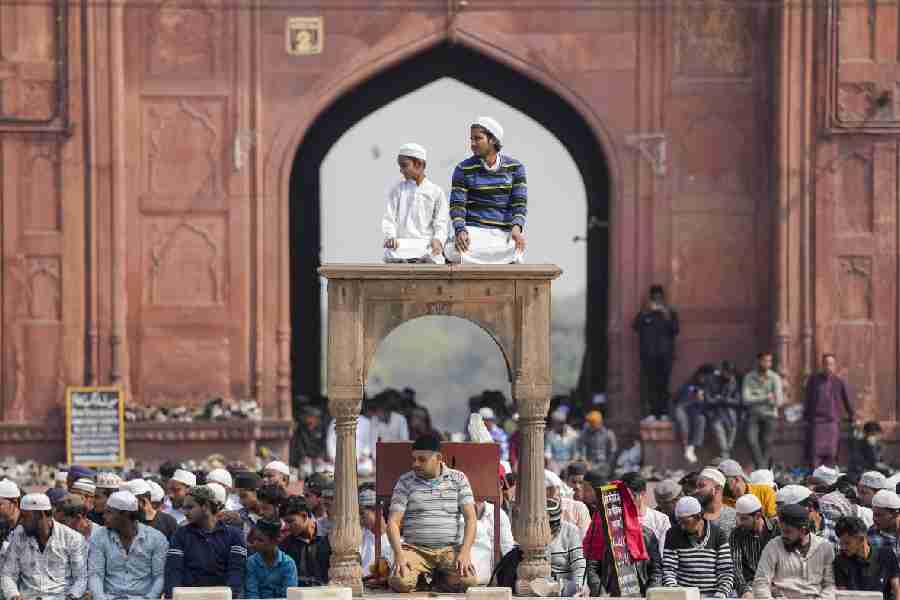

We thus live in an age where war is not only waged with guns and missiles but also with pixels and bandwidth. A child sits beside the rubble of his home in Gaza, holding the remains of his mother; a Ukrainian soldier bleeds into the snow; a protester in Belgrade is dragged across the pavement — all of this arrives in our palms, glowing on our screens between a food reel and a meme. Such sights could once bring the world to a standstill; today, they get lost among a deluge of countless other similar images, morphing suffering into a spectacle. And the more we watch, the less we feel. The culture industry thus offers us not a genuine understanding of this violence but a distraction that masquerades as concern. And here we stand as voyeurs of violence.

Moreover, we no longer experience reality in its raw form; instead, we seek out what aligns with our comforts and existing beliefs. Algorithms manipulate narratives of suffering to fit our biases, converting conflict into a tailored stream of emotionally digestible content. Human anguish is repackaged and disseminated not for critical reflection but to keep us engaged and distracted. The more we consume, the more we become numb to it. As horror becomes routine, it loses its significance. When we treat suffering as a form of entertainment, our capacity for empathy declines. This normalisation of suffering is in itself a form of violence. And the system acknowledges, applauds our desensitisation. It bombards us with new images, increasingly rapidly, until the next death feels like déjà vu. Furthermore, when we engage with such portrayals of conflict, we often encounter established narratives that tend to benefit those in power. In doing so, they subtly eliminate complexity, historical contexts and nuances, thereby pushing us toward taking sides without encouraging inquiry.

Amidst this ceaseless flow of image and text, we relinquish the moral significance of our existence. We’ve become spectators without a collective memory; participants without a sense of morality. The glowing display of our phones not only highlights the anguish of victims but also our failure to grieve, to question, to comprehend the source of their misery.

Behind every image exists a story. We owe it to those who suffer before us to delve deeper and scrutinise the stories and narratives being presented to us. To battle passive spectatorship, we must reclaim our ability for reflection, emotional involvement, and bold action to pursue the truth.

Kinjal Alok studies in Maharashtra National Law University, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar