Armenians, Parsis and Jews, all largely from Eurasia and the Middle East, made Calcutta their home and settled here from about the late 18th century onwards. Each of these communities made significant contributions to the evolution of this port city where they faced no discrimination and could succeed in all walks of life. Names still well-known in Calcutta include those of Johannes Carapiet Galstaun, Arathoon Stephen, T.M. Thaddeus, Rustom Cowasjee Banaji, Jamshedji Framji Madan, Sir David Ezra, and General J.F.R. Jacob.

By the 1950s, for a host of reasons, Calcutta's micro-communities began to leave the city in search of better economic opportunities. Today, Parsi estimates indicate there are 575 Parsis left in Calcutta. The number of Armenians remaining is hotly debated, ranging from estimates of 200 to 2,000 depending on whom you talk to in the community. There are 50 to 60 children from the Armenian republic, Iraq and Iran who receive free education, board, and lodging at the Armenian School on Free School Street. The Armenian Church recognizes about 200 Armenians, but there are apparently many people of Armenian descent or with Armenian names who are not 'recognized'. They include Armenians baptized in the Armenian Apostolic Church and others of Armenian descent who are disputing the actions of the church committee, which (according to 'unrecognized Armenians') has non-Armenian members. 'Unrecognized Armenians' are not entitled to the many economic benefits the community provides its members.

Faced with the reality of their dwindling numbers, the Parsi and Armenian communities are confronting serious challenges regarding how they can sustain their respective identities and heritage. This numerical challenge is considerably complicated by the fact that both communities are heir to extensive community funds. The Jewish community, with less than 20 members, also with funds at its disposal, is in the process of trying to preserve its legacy through the renovation and maintenance of the city's three synagogues and the Jewish cemetery in Narkeldanga. The Jewish Girls School and the Talmud Torah are subsidized by community funds. In addition to these material remnants, I have tried to document our history, culture, and contributions through a digital archive so that the memory of Calcutta's Jewish past is not lost and is a reminder to the city, the nation and the world of how multiculturalism as practised in everyday life benefited Calcutta and contributed to its prosperity.

The challenge faced by the Parsis of Calcutta is being confronted in Mumbai as well, though the number of Parsis there has always been greater. At its zenith, Calcutta's Parsi community had about 3,000 members. Berjis Desai, a lawyer and journalist from the Mumbai Parsi community, addressed the Calcutta Parsis at Olpadwalla Hall this March. He presented statistics on the numerical strength of Zoroastrians worldwide, and held that the Parsis and their diaspora were already on the "threshold of insignificance". He suggested how they might be able to increase their numbers as a community in India as they "hurtle towards extinction".

Low marriage and fertility rates, emigration to other nations, and inter-marriage are key causes of the declining number of Parsis in India. In spite of the many schemes to reverse the shrinking demographics of the community, such as stipends to mothers for additional children, the government-sponsored Jiyo Parsicampaign, youth camps, fertility clinics and marriage bureaus, nothing seems to work in tackling the magnitude of the problem.

Desai advocates that in order for Parsis to increase the number of Zoroastrians in the community, they should consider changing their stance on inter-marriage. Today, it is reckoned that some 48 per cent of marriages in the Parsi community in India are inter-faith. Yet, to date and in keeping with the Zoroastrian faith, only Parsi fathers are entitled to pass on their faith. The refusal to recognize the children of Parsi mothers who have married out has caused numbers in an already small community to shrink further. Some Parsi women who have married non-Parsi men have had their children converted to the Zoroastrian faith, but this remains controversial and is not universally accepted by all religious authorities in the community.

Calcutta's Parsi Zoroastrian priests are conservative, and do not countenance this conversion of the children of non-Zoroastrian fathers to the Zoroastrian faith. While Calcutta's Parsi community is indeed accepting of the children of Parsi mothers born to non-Zoroastrian fathers, these children are not legally considered to be Parsis, but members of their father's community. They are thus not entitled to the legal and financial benefits available to Parsi Zoroastrians.

Desai says that given the Indian Constitution and the international treaties to which India is party, a challenge to the status quo could be mounted by Parsi women intermarrying on grounds of discrimination. According to Desai, these women might well be granted their demands by arguing that it is illegal to discriminate on the basis of gender. One wonders about the repercussions of such action on India's other minority communities, and how this could trigger the contentious issue of conversion more broadly. Desai suggests that over a period of time, Parsis could consider accepting as Zoroastrians those who are really spiritually keen to follow the faith. Those who wish to become Zoroastrians could do so for this reason, and not merely to prove a point or gain access to the Parsi charities. Ultimately, however, attempts to expand the numbers of Calcutta's Zoroastrians may prove futile; many members of the community are ageing.

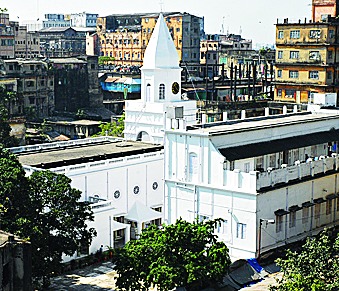

The Armenians of Calcutta are also dealing with the troubling issue of inter-marriage. However, their key intervention to sustain the community and utilize its vast resources has been to have Armenians from other parts of the world come to Calcutta to benefit from a fully paid high school education that includes board and lodging. Armenians in India are entitled to free education, medical care and accommodation when they require it. They can request community funds for other needs that arise. Some members of this community are deeply troubled that locals of Armenian descent are closed out, although they are often in dire need of those funds. The management of the church and the affairs of the trusts are vested in a lay committee, the members of which are directed by the high court to live within a 50-mile radius. The Apostolic Church of Etchmiadzin, Yerevan, Armenia plans to use the income and assets for the benefit of Armenia.

Calcutta's Chinese and Greek Orthodox micro-communities are also waning in terms of their presence in the city. As they, along with the Parsis and Armenians, contemplate their futures, we must find ways to preserve and celebrate Calcutta's distinctive multicultural legacy. Discussions are being held to give shape to the city's vibrant Chinese legacy. A creative and systematic plan to retain the history and culture of all the city's micro-communities could help rejuvenate its lagging tourist industry and enrich the city's memory and understanding of its past. As Eli Wiesel said: "Without memory, our existence would be barren and opaque, like a prison cell into which no light penetrates, like a tomb which rejects the living."