Legacies are strange beasts. Some can be completely forgotten until they are remembered. For instance, for a century no one recalled that the Spanish flu of 1918 killed more people in India than anywhere else; but now this fact is much deliberated as we are engulfed by another pandemic. Sometimes they are permanently influential — like the Bengal famine of 1942-43 represented the final erosion of whatever remained of the moral consensus that had sustained the British raj in India. Its legacy remains one of administrative incompetence combined with policy failures that created a vast human tragedy. The legacies of two very different warriors, whose anniversaries fall this month, are being refashioned in accordance with contemporary preoccupations.

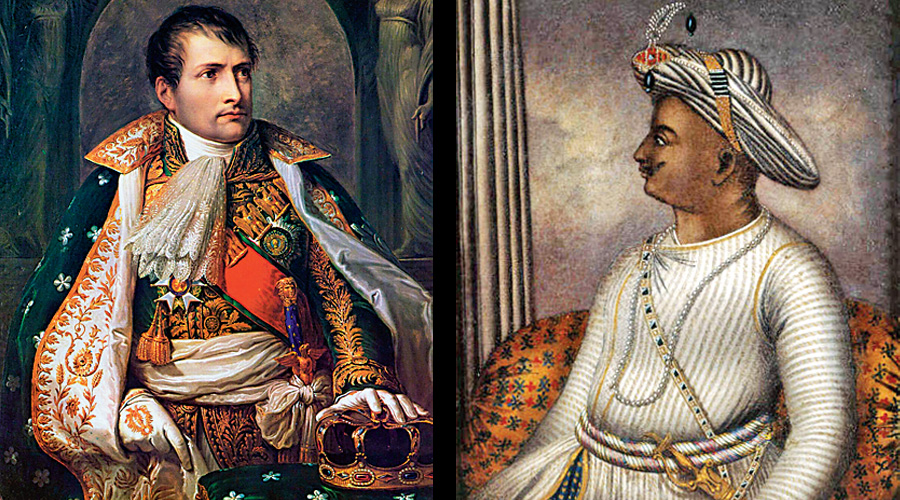

The 200th death anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte fell on May 5. His domination of all the continental powers in Europe, till he was finally worsted in Waterloo in 1815 by a concert led by Britain, should make him a hero for the French at least. Yet his legacy appears most contested in France even as the French president, Emmanuel Macron, paid tribute by laying a wreath at Napoleon’s tomb in Paris. “If his splendour resists the erosion of time, it is because his life carries in each of us an intimate echo,” Macron said. The headline following Macron’s speech was an evocative phrase he used — “Napoleon is a part of us.”

Also in May falls another important anniversary, not unrelated to Napoleon and equally controversial, but in India. On May 4, 1799, Tipu Sultan was killed while defending Srirangapatna against a British force. This defeat marked the beginning of a two-decade-long period in which the British overrode every power in peninsular and central India. Tipu Sultan had been a major adversary and his demonization in British accounts of the time and later was therefore of a correspondingly high order. A Napoleon-led expedition to Egypt earlier in the 1790s had an obvious eye on undermining the British in India and Tipu would have played a key role in this, given his position on the eastern coast. The British remained alive to any power in India linking up with the French till Napoleon’s final defeat. The danger of a possible alliance between Tipu and the French was by the late 1790s perhaps more imagined than real, but it was enough to ensure his removal.

For the critics of the French president, Macron, the high-profile commemoration of the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death was simple politics — there is a presidential election next year. His invocation of the best-known Frenchman of the modern world was seen also as a way of undercutting opposition on Macron’s right which has long seen Napoleon as a military genius and a national hero. Past French presidents had pointedly disassociated themselves from earlier commemorations since Napoleon was also seen as a warmonger and territorial aggrandizer whose ambitions caused widespread death and destruction in Europe. Additionally, one feature in particular made this divisive legacy even more controversial. In 1802, Napoleon decreed the restoration of slavery in French territories in the Caribbean, reversing the abolition of slavery which the French Revolution had effected. This act made France the only country to abolish slavery and then restitute it.

The supercharged debates about slavery and racism that have engulfed Europe and North America in recent years, especially the ‘Black Lives Matter’ hashtag, provide the context for this aspect of Napoleon’s legacy acquiring a larger-than-life character. For many, President Macron’s wading into this terrain reflected the ongoing debate in France about colonialism, racism and about how to address the aspirations of its Muslim population following the Prophet cartoons and blasphemy-related issues.

If Napoleon’s legacy, even in France, is divided and generates controversy to this day, so does Tipu Sultan’s in India. Two polarities define that public debate. In one, Tipu’s defiance of the British and the fact that he was prepared to fight to the end and not accept humiliating terms, as many other ruling princes of the time did, are his defining legacy. In the other, it is his bigotry and treatment of non-Muslims that stand out. Here, the British provide much of the ammunition for the demonization and vilification by his contemporary adversaries. Both ends of the debate are influenced by current divides, although admittedly Tipu Sultan’s defiance and refusal to accept the humiliating terms the British offered for settlement have a much stronger evidential basis. But as memories of the conquest and domination of India by an outside power fade, it is our internal fissures, sometimes real but more often imagined, that surface.

The portrayal of Tipu Sultan in contemporary British accounts, however, has other parallels. During the debate that followed the second Gulf War with the invasion of Iraq led by the United States of America, at least one reputed historian had drawn parallels between Saddam Hussein, Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1950s Egypt, the Mahdi in Sudan in the 1890s and Tipu in Mysore in the 1790s. If we use contemporary Foucauldian jargon, in each of these cases there was the moulding of discourse through power. Napoleon’s legacy and the contestations around it are of a different character, but here, too, there is more than a hint of France redefining itself both vis-à-vis Europe and its own citizens.

To return to legacies, we do not know for certain whether Winston Churchill actually said, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it”. But he certainly thought so. George Orwell, however, certainly did write, “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past”. In what manner this pandemic will remain as a milestone in our history and memory, we cannot say. Will it be akin to the influenza a century ago — largely forgotten until forcibly recalled by a new and similar calamity? Or will it be like Partition, the legacy of which is so alive in many quarters that it becomes part of the present? It is too early to say what the legacy of the Covid-19 pandemic on our own collective consciousness will be, but that for many of us it is a formative moment is incontestable. Yet, how the future will recall this present remains to be seen.