Apart from the thousands whose lives he touched and often changed through his mass meetings, writings and speeches, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi had significant relationships with a range of people at different phases of his life. In the last years, two Bengalis and a grand-nephew became very close to Gandhi. They were Sudhir Ghosh, the anthropologist, Nirmal Kumar Bose, and the amateur photographer, Kanu Gandhi. It was also a time when events in Bengal, particularly the horror of Noakhali, occupied Gandhi greatly. While Kanu took many photographs of these days, some years after his assassination, Sudhir Ghosh wrote Gandhi's Emissary, and, in My Days with Gandhi, Nirmal Bose described in detail Gandhi's mental anguish during those dire weeks at Noakhali. A close reading of the books, together with the photographs, provides little known insights into a crucial time for Gandhi and the country as well.

Serendipity brought the two men to Gandhi's door, while Kanu's love for photography led his grand-uncle to organize equipment for him. After his stint at the University of Cambridge, Ghosh became close to the Quakers, and with Horace Alexander and other pacifists, he came to Bengal to do cyclone and post-famine work. In course of time, Gandhi met him and decided that he should be involved in his work in the region. More important, Ghosh became a part of the informal channel of communication between the Cabinet Mission and Gandhi at a time when crucial talks were on about the transfer of power. Nirmal Kumar Bose was his secretary in the mid-1940s and accompanied Gandhi to Noakhali, as his "companion and interpreter".

Following Direct Action Day in August 1946, the region had seen untold violence, many deaths, rapes and forced conversions. On October 19, after a report from Bidhan Chandra Roy on the situation, Gandhi decided to go to Noakhali. In early November, he started his tour, which took seven weeks of walking barefoot through 47 villages. His base was a half-burnt dhobi's house in the village of Chandipur, where he stayed till January 1, 1947. Ghosh who needed to meet him to discuss some letters that the leader had wanted to write to Lord Pethick-Lawrence and Sir Stafford Cripps, both of the Cabinet Mission, did not find it easy "to discover the washerman's house in the deep darkness of the Noakhali village in the midst of a forest of 'supari' trees; but a village boy guided [him] ultimately to the right place". Although on arrival, Ghosh told Gandhi that he was also carrying letters from Nehru and Patel for him, he was first asked whether he had brought his mosquito net with him. "I had to admit that I had not. So he went for me. 'You were born in Bengal; don't you know that it is impossible to sleep in these Noakhali villages without a mosquito net?'" Soon, Manu Gandhi helped out and the conversation turned to the letters. After he had heard them read out by Ghosh, he said, "So they want me to go back to Delhi, do they?' He pondered the letters and the request for a while, but decided,"No, my place is here, I will stay here".

Sudhir Ghosh spent a few days with Gandhi, who was walking barefoot from village to village, looking at hundreds of burnt and destroyed homesteads and buildings [photograph], sleeping wherever he was given shelter and eating the food offered to him. Ghosh commented that "his only concern was to heal the wounds - not to apportion blame". As he walked, he appealed to both communities to keep the peace. He asked villagers to pledge that they would not attack one another, and in order to see whether people abided by it, he would wait for a few days in the particular village. With him were Manu and "a Bengali interpreter". This was none other than N.K. Bose.

Apart from Manu and Kanu who had come to record Gandhi's Noakhali padyatra, Bose was the other constant factor in the run-down hut. Spinning occupied an important place in the daily routine, and this was usually at two in the afternoon. Gandhi used to spin half a hank or 430 yards every day and while he sat spinning, Bose wrote, "We used to read out the daily papers to him, because the post arrived in Noakhali not earlier than midday." Those days were full of introspection if not remorse and Gandhi was deeply distressed at the ambiguous role of H.S. Suhrawardy, chief minister of Bengal. He told Bose, "Never in my life has the path been so... dim before me... today my intelligence is beaten (mera dimag har jata hai). I do not know how to deal with him [Suhrawardy]". Bose continued, "I heard him muttering to himself several times during the day, 'What should I do! What should I do! ( kya karun? kya karun?).'"

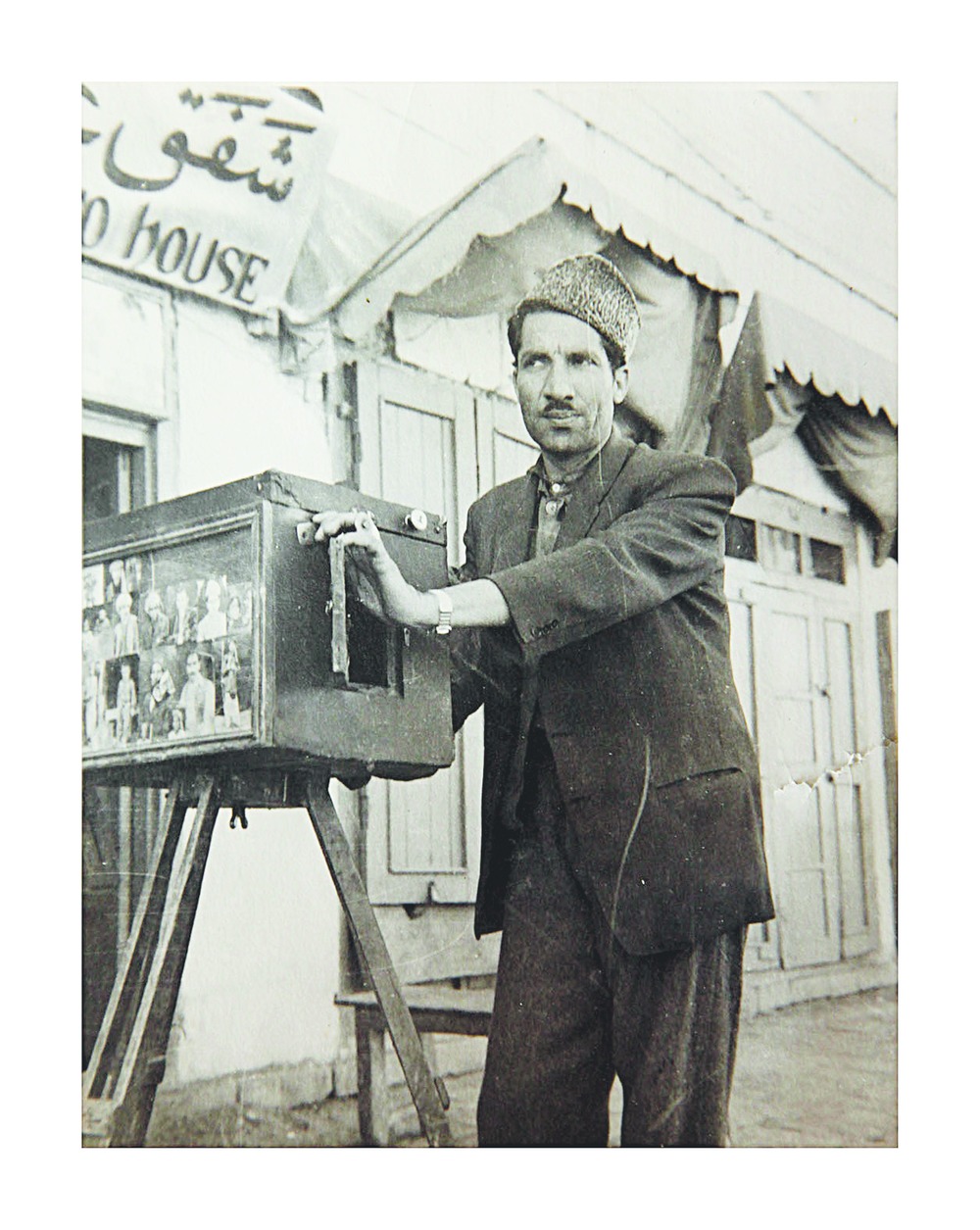

Some years ago, a German researcher discovered a cache of Kanu Gandhi's photographs of the last decade of the Mahatma's life. Through his Nazar Foundation, the photographer, Prashant Panjiar, has brought these into the public domain in Kanu's Gandhi. Although he was a deeply saddened man, Gandhi did not stop Kanu from photographing what was to be his last major public assertion that violence needed to be countered with a different kind of engagement. A number of the photographs of Gandhi's Noakhali days are blurred, out of focus. It is possible that the photographer was moving fast and perhaps even running to be able to get the right angle as the small procession moved along, or someone shook his arm. However, neither Kanu nor Sanjeev Saith, editor of the collection, discarded these images: they recorded a far too significant period in the 77-year-old man's life. It was a vital challenge to his moral authority, and that he succeeded was more important to him than to be at talks in New Delhi. Kanu was well aware of the need to represent Noakhali to the world - and, as on many other occasions, his camera recorded the moment by, as Panjiar commented in his biographical note, an "unconventional use of the foreground, breaking many of the accepted rules of composition". As Kanu was not to be judged by professional standards, blurred images or those with double exposure "find pride of place, lovingly pasted by his own hands in the few pages of his albums that survive", in Panjiar's description. Clearly, the photographer, an insider in every sense of the term who was well aware of the narrative behind each image, was reluctant to edit out any of them.

As a member of his personal staff at the Sevagram Ashram, Kanu started photographing Gandhi in 1936; he was able to buy a Rolleiflex and a roll of film with the Rs 100 given to him by the industrialist, Ghanshyam Das Birla, on the request of Gandhi. Aware of the teenager's compelling interest, Gandhi allowed him to take photographs, laying down a protocol, much of which was to be followed by all photographers - no flash, no posed images - and in this case, no funds from the ashram to fund Kanu's photography.

Of the close to a hundred photographs in the slim volume, there are some that stand out, not necessarily for their quality but for what they convey - the occasion, the ambience, the mood. There are many images that are historic, the dramatis personae being important players in the country's future. Others are of the Sevagram days, of the quotidian and everydayness of ashram life: then there are many images that only an insider could take - those of Gandhi resting and the one taken at 4 am, where with his head covered, he is reading a letter. It is in Sodepur ashram near Calcutta and it is 1946. It is November and it is cold, the bright light in the corner highlighting Gandhi and catching Sushila Nayar in chiaroscuro. Or there is the one of him looking out of a train window; His hands are folded and he looks pensive. Kanu was obviously standing close to him, inside the compartment.

The final sequence, that of his stay in Noakhali, is a chilling reminder of the horror and suffering of communal violence. Kanu Gandhi had stayed behind in Noakhali on Gandhi's instructions, and though he was not there on the fateful January morning, the book ends with images of the blood-spattered cloth and memorial plaque at Birla House. If Sudhir Ghosh and N.K. Bose were able to convey with candour Gandhi's political acumen and doggedness in sticking to his experiments, Kanu Gandhi's interestingly composed photographs document important aspects of his life - meetings, travel, fasts, walks through troubled areas, political negotiations and moments of rest and communion with Kasturba. Text and image match to record the action-packed last years of a man whom his friend, C.F. Andrews, referred to as "a saint of action rather than of contemplation".