In early June, the senior Congress leader, Jairam Ramesh, began using the hashtag, Emergency@11, in his daily posts charging the Narendra Modi government with various errors, mistakes, and crimes. This was in anticipation of what Ramesh knew would come later in the month; namely, the prime minister’s invocation of the 50th anniversary of the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi and her Congress Party. Through that hashtag, Ramesh was suggesting that while Indira’s Emergency lasted less than two years, Modi’s period of authoritarian rule had extended for more than a decade.

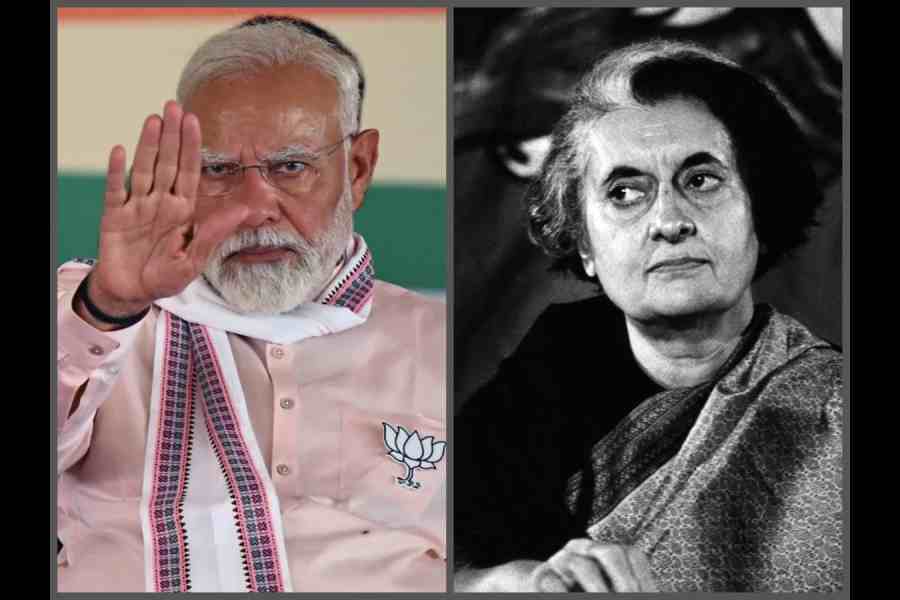

I myself came of age during Indira Gandhi’s prime ministership, and am growing old during Narendra Modi’s prime ministership. In this column, I shall venture to compare their political legacies, drawing both on personal experience and on academic research. (I shall leave the assessment of their economic and foreign policy legacies to scholars who understand those subjects better than I do.)

To the historian, there are five striking similarities between these two prime ministers separated in time and by ideological affiliation. To begin with, Modi, like Indira, has used his political authority to construct a mammoth personality cult, representing himself as the sole embodiment of the party, the government, the State, the nation itself. This cult is sustained by the public exchequer and burnished by the sycophants around him.

Second, like Indira, Modi has worked assiduously to undermine institutions whose independence is vital to democratic functioning. It was Indira who first spoke of a “committed bureaucracy” and a “committed judiciary”, an idea that Modi has adopted as his own. Although unlike Indira, Modi has not declared a formal Emergency, he has shown a similar disregard for the processes of constitutional democracy. Indira intimidated the press into suppressing the truth; Modi coerces it into telling lies. The bureaucracy is even less independent than it was in the 1970s; the investigative agencies used even more often to silence political opponents.

Third, Modi, like Indira, has adopted a unilateral rather than consultative mode of decision-making, violating the spirit of the Constitution, where the prime minister is presumed to be the first among equals and is not supposed to act in the way an all-powerful American president can. All through Indira’s reign, there was only one person whose advice she took seriously; first this was P.N. Haksar, then Sanjay Gandhi. Likewise with Modi; it is Amit Shah, and Amit Shah alone, whom he trusts. And Shah is as much a votary of non-transparent, authoritarian methods of rule as his boss.

Fourth, like Indira, Modi has sought to eviscerate Indian federalism. While Indira used the blunt instrument of Article 356 to dismiss state governments run by non-Congress parties, Modi has weaponised the technically non-partisan office of the governor to weaken elected governments. The BJP under Modi and Shah has also used its infamous ‘washing machine’ to break Opposition parties and install BJP state governments in violation of the popular mandate.

Fifth, like Indira, Modi has stoked hyper-nationalism to consolidate his rule. Like her, he has used the party, the State, and the media to claim that only he can represent what India wants and what Indians desire. The jingoism thus nurtured dismisses all criticism as motivated, as being allegedly fuelled by foreign powers. Indira went so far as to insinuate that the great patriot, Jayaprakash Narayan, was a Western agent. Now, the BJP’s ecosystem accuses the leader of the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi, of being in the pay of George Soros.

Such are the similarities. I now turn to the differences, of which two are of particular significance. First, despite her dictatorial ways, Indira upheld the plural idea of India encoded in the Constitution, wherein citizenship is not defined in terms of language, religion, or ethnicity. While Jawaharlal Nehru, arguably an even more principled secularist, could not secure the appointment of a single Muslim chief minister in a Congress-ruled state, Indira was able to appoint as many as four. Indira also famously refused to dismiss her Sikh bodyguards, paying for this act of principle with her life.

On the other hand, Narendra Modi is a thoroughgoing majoritarian, as dogmatically devoted as any of his fellow swayamsevaks to the construction of a Hindu rashtra in which the nation’s politics, cultural ethos and style of administration shall be determined by right-wing Hindus alone, and where Muslims and even Christians will be accorded second-class status. Eleven years of Modi’s prime ministership have exposed his ‘Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas’ for the hypocritical humbug one knew it all along to be. Of the 800-plus MPs sent by the BJP to the Lok Sabha in the elections of 2014, 2019, and 2024, not one was a Muslim. And outside Parliament, physical attacks on Indian Muslims, the bulldozing of Indian Muslim homes, the taunting and stigmatisation of Indian Muslims, even the forcible expulsion of Indian Muslims to other countries, all proceed apace, cheered on by Modi’s supporters and by the section of the media memorably characterised as ‘Lashkar-e-Noida’.

Indira’s belief that our country belonged equally to all Indians regardless of their religion admirably marked her out from the majoritarian Modi. On the other hand, the second major difference between them brings her discredit. For, by anointing her son, Sanjay, as her successor during the Emergency and, then, after Sanjay’s death in 1980, making her other son, Rajiv, her heir, she introduced a pernicious political practice that ran contrary to the history and heritage of the Congress Party in which none of Mahatma Gandhi’s children became an MP or minister after Independence, although all four had gone to prison during the freedom struggle.

Indira’s conversion of the country’s oldest political party into a family firm encouraged leaders of other parties to do likewise. The Shiv Sena, the DMK, the Akalis, and the TMC once stood for regional pride; now, that often takes second place to the perpetuation of the rule of the Thackerays, the Karunanidhis, the Badals, and the Banerjees, respectively. Likewise, the SP and the RJD stand for the continuation of family rule rather than for socialist ideology.

Modi’s parents were not in politics, and he has no children. This, in electoral terms, constitutes a colossal (and continuing) advantage he holds over his putative prime ministerial rival, whose elevated status in the Congress Party is owed entirely to the fact that he is the son of Rajiv and Sonia Gandhi and the grandson of Indira Gandhi. The contrast between Modi the self-made politician and Rahul the entitled dynast contributed in good measure to the BJP’s victory in the last three general elections, and it may yet help them in the next. More generally, the national dominance of the BJP is enabled by the dynastic politics of the major parties opposed to them. This is a brutal fact that too many brave and well-meaning opponents of Hindu majoritarianism are unable or unwilling to acknowledge. Dynastic politics is one legacy of the Emergency that continues to exercise a baleful influence on Indian democracy in the present.

Of all the prime ministers we have had since Independence, Indira Gandhi and Narendra Modi have been the two with instinctively authoritarian instincts. Whose regime has been worse? When reckoned in terms of freedom of expression, we are slightly better placed now, given the existence of a few independent websites and regional newspapers which tell the truth as it should be told. Likewise, there is a greater space for political opposition, principally because while in the Emergency all but one state government was controlled by the Congress, now more than half-a-dozen states are in the hands of parties strongly opposed to the BJP.

On the other hand, since May 2014, our public institutions have been deeply and perhaps irreversibly damaged by excessive political interference. The bureaucracy and the diplomatic corps are largely compromised; the higher judiciary, only slightly less so. The tax authorities and the regulatory agencies are more ‘committed’ to their political bosses than ever before; so, arguably, is the Election Commission.

Finally, and most worryingly, under Modi’s watch the poison of religious bigotry has spread far, deep, and wide. This bigotry is increasingly manifest in everyday life on the ground, and in the speech and conduct of senior cabinet ministers (including the home minister and, on occasion, the prime minister), and of chief ministers of the BJP (notably those of Uttar Pradesh and Assam). The armed forces, once so proudly secular and non-sectarian, are increasingly asked to demonstrate a public allegiance to Hinduism and Hindu domination. This fusion of majoritarianism with authoritarianism constitutes the most damaging aspect of Narendra Modi’s style of governance, which, even after he has finally demitted office, may take decades to undo and reverse.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in