The visit to Beijing by the foreign secretary, Vikram Misri, over the past two days marks the latest chapter in a rapid series of high-level meetings between Indian and Chinese officials as the Asian giants try to bring some normalcy back to their ties after years of heightened tensions. Mr Misri met not only his counterpart, the Chinese vice-foreign minister, but also China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, and senior officials of the Chinese Communist Party. Aside from the rhetoric that emerged from the Chinese side following these meetings, calling for the two nations to meet halfway and focus on substantive collaboration, the meetings themselves point to the importance that both sides appear to be attaching to their attempted détente. Ending more than four years of a military standoff along their de facto Himalayan border, India and China agreed last October to withdraw troops from friction points along the Line of Actual Control. Right after that, Prime Minister Narendra Modi met the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, on the margins of the BRICS summit in Russia. Since then, Mr Wang has met — in separate interactions — the national security advisor, Ajit Doval, and the external affairs minister, S. Jaishankar. The defence minister, Rajnath Singh, also met his Chinese counterpart, Dong Jun, in November.

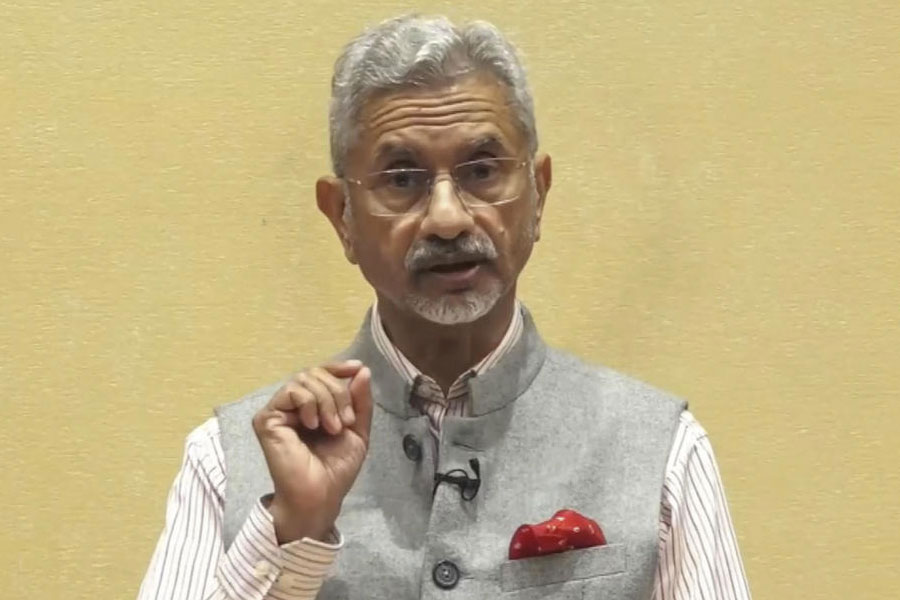

While these hectic parleys demonstrate intent on both sides to try to build on the momentum from the border pullback, the recent crises in their relationship have deepened mutual distrust that will not go away with a few meetings. The past few months have seen India raise concerns about a new Chinese plan to build the world’s largest dam in Tibet on the upstream part of what India calls the Brahmaputra. New Delhi fears that the dam could allow Beijing to weaponise water, either by denying India adequate water or by unleashing floods. Meanwhile, Mr Jaishankar met his counterparts from the United States of America, Japan and Australia in Washington on the margins of the swearing-in ceremony of the US president, Donald Trump. The Quad grouping issued a statement that was more overtly critical of China and its territorial ambitions in the Indo-Pacific than has been the norm. No one expects New Delhi and Beijing to be best friends. But they do not need to be enemies either. If they can each benefit from the other’s growing economy, collaborate on shared concerns like climate change, and maintain peace on the border, that would be a win for both.