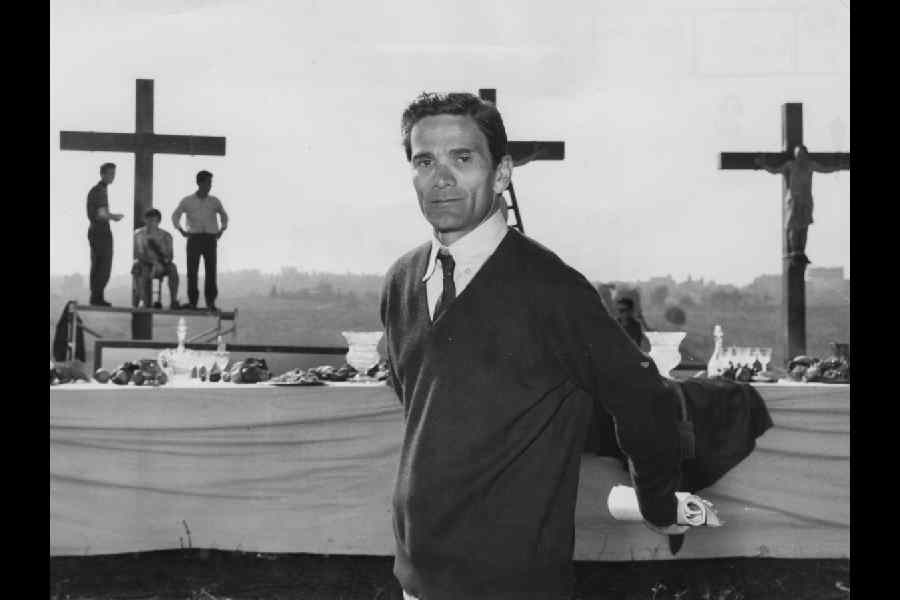

Fifty years ago, Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) fell foul of an extreme-Right conspiracy. Murdered on the beaches of Ostia near Rome, ostensibly for his homosexuality, Pasolini passed into a world where there is no death, only homages to creative subversion or heated controversies born more of social prejudice combined with political enmity than any attempt to understand the gravitas of the issues that haunted him.

Perhaps the most distinguished Italian holistic intellectual to have been a consistent supporter of Pasolini was none other than the novelist and short-story teller, Alberto Moravia, a cineaste of no mean order. Considering the comparative popularity of the varied art forms in which Pasolini engaged himself, it is perhaps understandable that the world should remember him as primarily a film-maker, forgetting or glossing over his enormous achievements as an unforgiving poet of the lower depths; of the godforsaken shanty towns whose proletarian or sub-proletarian inhabitants had learnt to accept deprivation and disgrace as their inevitable fate. If occasional defiance were to rear its head, it would be instantly scotched by a combination of tyrannical forces, including the bourgeoisie, the Church, the media, the political Establishment, and, most sadly, enemies lurking within the fold of the oppressed.

The days in which Pasolini came of age, the seven hills of Rome bristled with the anger of the popular classes and the Tiber overflowed with disappointment at the triumph of the culture of complicity of the wealthy and the powerful. Together, these provided Pasolini with the wherewithal to sculpt his protest in celluloid in an idiom absent in Italian cinema before or after him. The quintessential rebel that was Pasolini, he would not, like Spartacus before him, take lightly the slavery of the mind and the bondage of the body to which the disenfranchised had been condemned. In the end, both these iconic figures came to a violent end for their polemical and sexual overenthusiasms.

Moravia’s observations on Pasolini the poet are worthy of recall not only because he himself was an exponent of high literature frequently peopled by lowly characters but also for his deep knowledge of, and support for, a certain kind of ‘people’s cinema’ that rested on explosive possibilities of deliverance for malcontents in search of sighting the sun and thereby defeating the dark. Moravia’s admiration for Pasolini’s poetry knows no bounds: “Pasolini is the greatest Italian poet in the second half of the 20th century. One poet is not worth more than another. But Pasolini wrote more, and more importantly than the others. Pasolini was fated to grow up during a disastrous period of Italian history, at a time of unparalleled catastrophe: a military debacle, with two armies fighting on Italian soil. At the same time, the industrial revolution was drawing millions of men to the cities, away from the peasant civilization which Pasolini loved and in which the roots of his poetry lay. Here then we have two of the main themes of Pasolini’s poetry: lamentation for the devastated, prostrate and humiliated nation; and nostalgia for the lost peasant.”

Reading Moravia on Pasolini half a century after the latter’s death, it is difficult not to be struck by how well the litterateur understood the literary outpourings of his assassinated countryman, making him place them above his films, but without denying in any way their uniqueness and the purity of their grandeur. Where Pasolini’s critics, conservative and constipated, could see only obscenity and perversion, Moravia, and the poet, critic and translator, Giovanni Raboni, delighted in a return to a medieval past which could be both glorious and cruel.

Often working with devastating effect around his belief in the dialectics between politics and religion, Pasolini’s films have stood the test of time, albeit in well-defined radical circles. But he is, arguably, at his best in what is commonly regarded to be his most distinguished work, namely, The Gospel According to St. Matthew, where Christ is a revolutionary, ‘weaponising’ peace and the brotherhood of man in an ambience of violence perpetrated by the Romans working in league with the Jewish priestly class. Pasolini argued that given the socio-political conditions in which Christ lived and worked, what other course than turning the other cheek to the oppressor could he have chosen to reach his message effectively to his subaltern constituency. When an ossified section of the Italian Communist Party took exception to Pasolini’s choice of subject, he retorted that he would be a fraud if, even whilst keeping in mind his Marxist persuasion, he were to deny or disown the history and the traditions of the Judeo-Christian civilisation to which he had been born and which had been in operation for centuries in the land of his birth.

In this context, Pasolini appears to have been quite clear about how he saw Christ. He ‘humanised’ Christ to the extent that his film was anathema to the conservatives of the Catholic clergy but more than welcome to enlightened Christians on an international scale. For instance, Bud Keiser, the American producer of Romero — about the martyred Salvadoran liberation theologian — is on record stating that Pasolini’s realistic interpretation of the life of Christ still holds good from a cinematographic point of view precisely because it stays away from being reverential and, in fact, is rather sceptical in tone. Where most films to do with Christ or the saints end up, in a sense, mummifying them, something as special as The Gospel According to St. Matthew gives us a spiritual figure throbbing with life complete with possibilities of failure and atonement.

The recent upsurge of enthusiasm in Italy for fascist politics and the deathly cult of Benito Mussolini appears to have caused many right-minded, progressive film-lovers the world over to turn with renewed interest to Pasolini’s oeuvre expressing his non-doctrinaire views on Marxism; or his seemingly controversial but actually creative approach to religious faith. As far as Pasolini was concerned, Marx ought not to be degraded into an object of deification, a line which one daresay would have been wholeheartedly supported by Marx himself. Equally, Christ was not the son of a non-existent god, but a good and simple figure of blood and bones who set a grand example of struggle and sacrifice for his fellows. Naturally, such a rare, scandalous artist had to be done away with by any means available to the merchants of death.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee is the author of Despair and Defiance: The Worker in Indian Cinema