The 170th birth anniversary of Bram Stoker is probably not the best time to say that Dracula was a surprisingly boring book. The truth, however, is that the 1897 classic, featuring the world's most famous vampire, ought to have been a lot better than it was. It peaks too early, there are too many narrators, and far too little of Count Dracula himself. (This may have been the point, given that he was supposed to be a mysterious figure, but it mars the book all the same.)

How, then, did Stoker's Dracula grip public imagination so strongly that he remains wildly popular even today? After all, by the time Stoker put pen to paper, he had a number of predecessors to model his creation on. The count's 'brides' remind one of J. Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla (1872), while Dracula himself echoes James Malcolm Rymer's Varney. But it was not just Dracula's abilities or demeanour that made him terrifying; it was the way in which Stoker made him embody the fears of Victorian Britain. He was the 'other' from a foreign land preying on good English girls; he was the devil's son, threatening religious Christian society. Stoker's Dracula may not have been the first vampire in literature, but he became the template future authors used.

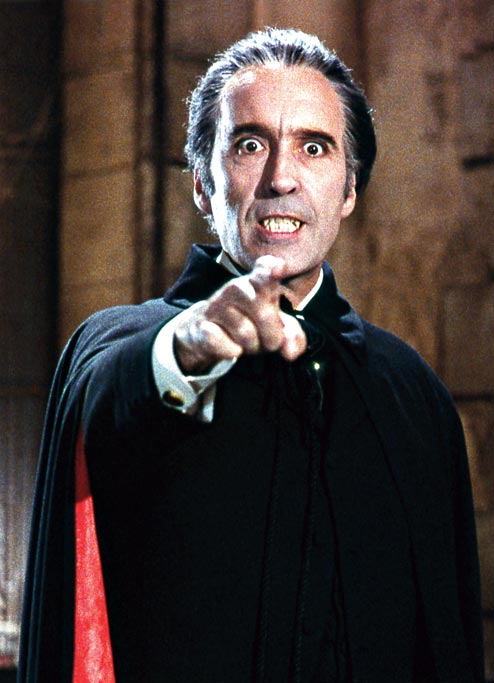

If the lure of the children of the night grew with the publication of Dracula, it became irresistible when motion pictures arrived. Nosferatu (1922) is arguably still the most faithful adaptation of Dracula. Thereafter, Bela Lugosi brought about the count's first major transformation. But the most notable point in this development was during the Cold War, when Horror of Dracula (1958) was released, with Christopher Lee in a career-defining role. His count was so menacing - much like America's view of its rivals - that in the 1966 sequel, he had no lines. All he did was snarl at the camera.

Vampires in popular culture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries were updated to fit the times - they went from having the pouffed hair of the disco era to the brooding good looks and irreverent power of today's hipsters ( True Blood, the Twilight series). In between, there was Leslie Nielsen, who brought great comic charm to Dracula in a spoof.

The truth is that literary tropes for horror endure because they are fluid. Vampires have figured in fiction for centuries because they keep adapting to the needs - fears? - of society. Stoker knew this in 1897; since then, the vampire's image has been a work in progress. Perhaps this is why Dracula cannot see his own reflection - it keeps changing to mirror the times.