Donald Trump’s curveball, imposing a 25% tariff on all Indian imports, followed up by a sinker, imposing a further punitive tariff of 25%, have taken India by surprise. The concomitant cozying up to Pakistan —throwing up some generous dollies for Field Marshal Asim Munir to hit out of the park — was equally unexpected.

Most commentators have attributed the moves to Trumpian whimsy. Some have said he was unhappy with India not crediting him for ending the recent conflict with Pakistan. Others have called it a negotiation tactic to get a better deal during trade talks. Pinning this volte-face on Trump may seem intuitive. After all, trampling over a relationship rescued from the brink and carefully nurtured over two decades requires either extreme self-belief or incredible recklessness. Trump isn’t lacking in either of these attributes.

But history shows this is not the first time that the United States of America has gone out of its way to show an emerging India its place in the world. Trump’s latest move, as idiosyncratic as it may seem, is reminiscent of a similar sequence of events from post-World War II Japan. This history lesson might come in handy for an Indian foreign policy ecosystem that appears to have been caught off-guard.

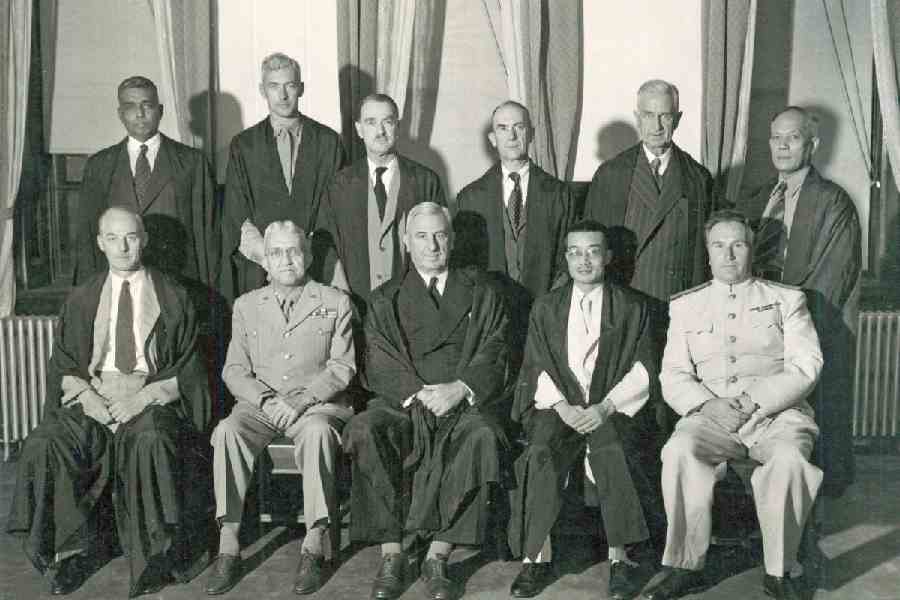

The Tokyo Trials had ended in November 1948 with seven Japanese “Class A war criminals” being executed and 16 being sentenced to life imprisonment. The Indian judge on the tribunal, Radhabinod Pal, had written a stirring dissent acquitting all Japanese defendants using a combination of legal and rhetorical arguments. While one might imagine that his dissent would upset the Americans, nothing of the sort happened.

Despite his initial reservations that the Tokyo Trials should not be delayed unnecessarily, the supreme commander for the allied powers in Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, had been generous in expanding the pool of judges on the bench to include an Indian judge. He was personally solicitous to Pal, even sending his personal plane on one occasion to Hong Kong to bring Pal to Japan quickly. Despite his stirring dissent, MacArthur did not see Pal’s views as offensive. In fact, it only added to the perception of fairness of the trial and the rule of law, a key pillar of American democracy that it was now looking to export to Japan.

The Government of India, on the other hand, was initially sceptical of Pal’s views, with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru criticising its “wild and sweeping statements”. However, it quickly corrected course when it saw in the judgment some potential in making India more visible in Japan. This is why Benegal Rama Rau, the then Indian ambassador to Japan and later governor of the Reserve Bank of India, advised his counterparts in New Delhi to not openly denounce the judgment whatever their misgivings. His successor, Birendra Narayan Chakraborty, later governor of Haryana, said that several American officials in Japan, including Major General Charles A. Willoughby who worked directly with MacArthur, had supported Pal’s views. M.A. Rauf, the Indian ambassador from 1952, wrote on record that Pal’s views had earned India “a certain amount of goodwill”. Finally, Nehru himself completed this shift in position. Replying to a question in Parliament on May 14, 1954, he called Pal’s opinion “a learned dissenting judgment”.

By this time, the Americans too had changed their strategy in Japan almost entirely. They were initially keen on planting the flag of democracy and the rule of law in Japan, a quest in which Pal’s dissent fitted in quite neatly. But in less than three years, Japan was no longer a lab for an American democracy experiment. It had to be fortified to become a bulwark against Russian and Chinese communism. The Treaty of San Francisco was signed in late 1951, and ratified in early 1952, to bring the Allied occupation of Japan to an end. Amongst the original participants in the Tokyo Trial, China, the USSR and India neither signed nor ratified the treaty. India’s opposition was principled — the future of Asia should not be determined by the US, including keeping bases in the region for its own military interests. A principled disagreement, just like Pal’s dissenting judgment, should ordinarily have been water off a duck’s back, especially for a country so publicly celebratory of freedom of expression and diversity of views. But that was not to be. India was threatening to become overly prominent in the Far East and it had to be shown its place.

As part of the changed American policy, it was decided that all Japanese Class A war criminals would be released from prison. As per the clear wording of the treaty, this decision would be taken by the majority of governments whose judges participated in the trial. Consequently, in November 1952, the Government of Japan approached

the Government of India for its consent to release the prisoners. India saw

this as a validation of Pal’s views and gave its consent.

In March 1953, out of the blue, the Japanese sheepishly informed India that its consent to release the prisoners did not matter because the US, supported by the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, France and the Netherlands, had taken the view that India, which had not signed the San Francisco Treaty, would be excluded from this decision. The matter was only academic since India had anyway consented to releasing them. Yet, the US wanted to make a larger point. It deliberately and very publicly alienated India and ensured that each of the other Allied governments also parroted its own stand. Though India was ready to play ball, it was not allowed to take the field. Nehru expressed his surprise openly — “The Government of India take(s) a grave view of this arbitrary use of authority”, he said in Parliament.

Not content at resting there however, the US and its allies proposed that Pakistan be given a vote on the issue since it had signed the San Francisco Treaty. This was bizarre since Pakistan had neither participated in the trial, nor did it have anything to do with the prosecution of Japanese war criminals till then. But American lawyers, supported by their British counterparts, made a specious legal argument that it was British India that was represented on the tribunal and Pakistan as one of the successors to British India had the right to participate. Taking away an Indian vote using a sleight of hand was humiliating enough. But, as The Manchester Guardian wrote at the time, replacing it with a vote for Pakistan was like “waving the reddest flag before the Indian bull”. It was surprising, cunning and meant to demonstrate to India in capital letters and multiple exclamation marks who called the shots.

Cut to 2025 and Trump has only followed this script. He may be whimsical and unpredictable. But his move to impose tariffs on India and gravitate to Pakistan is neither of those things, at least not entirely. Unlike baseball, where a batter is out after three strikes, when it comes to a real American foreign policy game, the batter is out whenever the US thinks he is out. India found out the hard way in 1953 and now again in 2025. It should learn its lessons and not attribute America’s latest move to Trump’s mood swings alone.

Arghya Sengupta is Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal