Particularly vulnerable tribal groups, earlier known as primitive tribal groups, are the sort of people you may never meet unless you take the trouble to look for them. In Jharkhand, they live in small hamlets scattered over the nooks and crannies of the state’s undulating forests. Without a purpose and some local guidance, it is unlikely that anything will take you there.

Last month, the Sahayata Kendra (help centre for rural workers) in Manika block of Latehar district completed a house-to-house survey of all the PVTG families in the block, and also in the adjacent block of Satbarwa in Palamu district. We found 325 PVTG households — spread over 18 hamlets — in these two blocks, compared with 256 listed in the Socio-Economic and Caste Census of 2011. All of them belong to the Parhaiya community. They came across as uprooted people, who have been deprived of their traditional resources and are now struggling to latch on to new sources of livelihood.

PVTG families in the area used to subsist mainly on forest-based activities such as hunting, gathering, selling minor forest products (roots, berries, wood, mahua, tendu, lac, herbs, among others) and manufacturing simple items from straw, bamboo and such. Not so long ago, the forests of Jharkhand were dense with flora and teeming with wildlife, but recent environmental degradation has taken a toll. Today, most PVTG families in Manika and Satbarwa subsist on a little farming, casual labour, and residual forest-based occupations such as making ropes or baskets. Some of them work as seasonal labourers in the rice fields or brick kilns of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, and occasionally migrate to more distant places.

Public facilities in PVTG hamlets are abysmal, in spite of some recent progress. None of the 18 hamlets we visited seemed to have a well-functioning school. Few had their own anganwadis, keeping child development services out of reach of most PVTG children. Health centres, banks and administrative offices are far away and public transport is nil. Government officials rarely visit these hamlets. Isolation, poverty and low education levels have turned PVTGs into sitting ducks for exploitative contractors and middlemen.

In this situation, PVTG families depend critically on two entitlements for their survival: social security pensions and food rations from the public distribution system.

Under a Supreme Court order of May 2, 2003, in the right to food case, Antyodaya ration cards are to be distributed to all PVTG households. This entitles them to 35 kgs of foodgrain per month from the PDS at a nominal price; in fact, for free in the case of Jharkhand. Among the 325 households we surveyed, 87 per cent were on the Antyodaya list. Further, Antyodaya households reported that they were receiving the bulk of their PDS entitlements: about 33 kgs per month on an average. This is good news of sorts in a state where PDS grain used to be siphoned off with abandon by corrupt dealers. Even the reduced levels of pilferage, however, are unacceptable, and a significant minority of PVTG households is still deprived of Antyodaya cards.

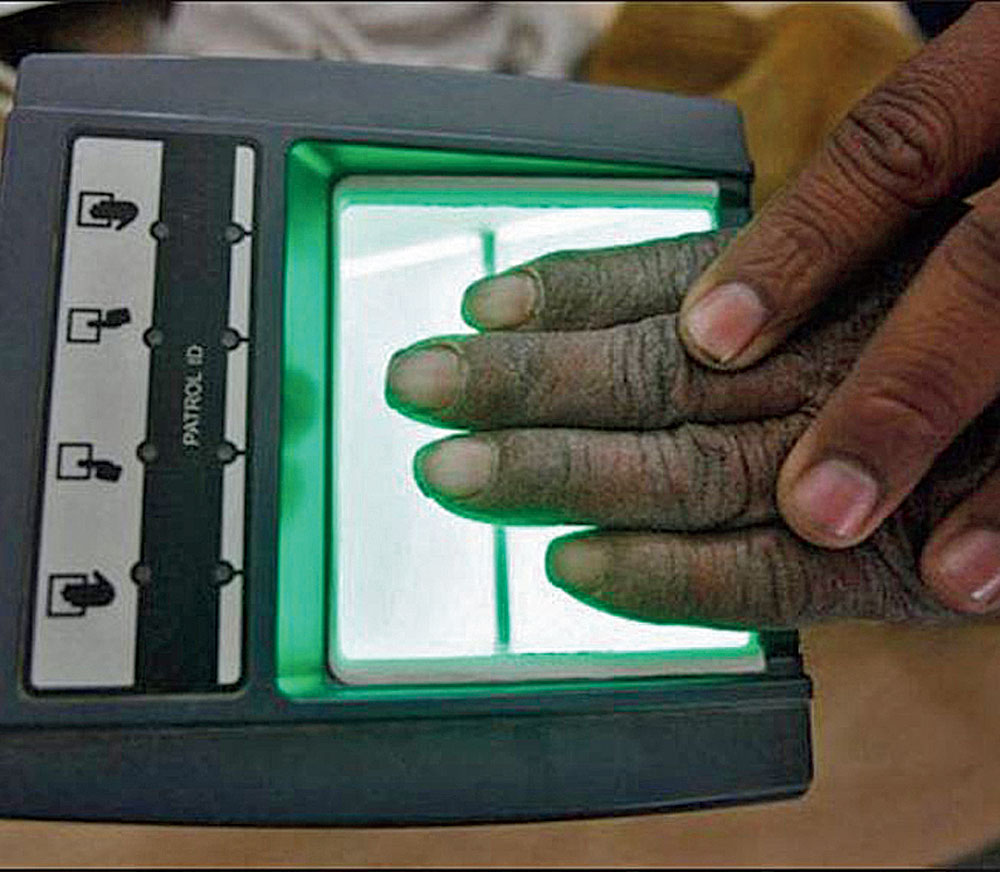

Turning to pensions. All PVTG families in Jharkhand are entitled to a pension of Rs 600 per month — if not under an existing old-age, widow or disability pension scheme, then under the state government’s special pension scheme for PVTGs. The survey, however, reveals that only two thirds of all PVTG households in the area are receiving a pension. One reason for this is that many pensions have been discontinued in recent years owing to Aadhaar-related problems. The main problem is that all pensioners in Jharkhand are now required to meet the e-KYC (electronic Know Your Customer) banking norms. This means that Aadhaar must be seeded in their bank account and also that the seeding must be verified through biometric authentication. In the absence of biometric facilities at the bank, pensioners have to go to a Pragya Kendra (customer service centre) for authentication, take a certificate from there to the bank, and then hope that the bank will complete the formalities in good time. Lapses, errors, glitches and delays abound. For pensioners, especially for the elderly, these hurdles are daunting. Many of them do not know what they are supposed to do or how to seek assistance if a problem arises. None of this has changed — so far — after the recent Supreme Court judgment on Aadhaar.

In our small sample of 325 households, 28 pensioners were currently deprived of their pension, mainly owing to Aadhaar-related problems. Another 30 or so had been temporarily deprived of their pension for several months, sometimes more than a year, at the time when they were struggling to meet the e-KYC norms. In cases of temporary discontinuation, there are no retrospective payments for the gap months after a pension is resumed.

The discontinuation of pensions is just one among a long series of Aadhaar-related problems that emerged from the survey. Examples include inability to get an Aadhaar card because of blindness or deformed hands, ration cards being cancelled for lack of Aadhaar linkage, children being refused admission for lack of Aadhaar, NREGA wage payments being rejected, bank accounts being frozen for lack of e-KYC, and problems of biometric authentication at the Pragya Kendras. More than 40 per cent of the respondents had experienced problems of this sort.

Aside from the pathologies of Aadhaar, PVTG families have to contend with merciless harassment from local exploiters. In Uchvabal village, a para-teacher, Krishna Ram, was caught trying to siphon off children’s scholarships. In Sewdhara, a PDS dealer, Dinesh Rai, measures food rations using a recycled tin instead of a weighing machine, pruning them to 31 kg per month instead of 35 kg. Pragya Kendra operators routinely take bribes for services, and one of them (in Namudag) tried to extort Rs 2,000 from an illiterate woman who needed help to apply for a pension. Another one, in Rewat Khurd, even siphoned off a Rs 56,000 housing subsidy from the account of an elderly widow who blindly lent her thumbprint for this purpose.

These and other acts of exploitation were brought up at a public hearing held in Manika on December 13. Block-level officials, however, did their best to protect the exploiters. The block supply officer, for instance, acted like Dinesh Rai’s well-wisher. Hopefully, the district administration will crack the whip, but who knows, crooks often have patrons in high places.

The experience of the Parhaiyas in Latehar and Palamu confirms something we have already learnt from other states: the PVTGs need special support and it is perfectly possible to help them. The existing support systems, however, are patchy and inadequate. Indeed, in spite of receiving some assistance from pensions and the PDS, the Parhaiyas continue to live in the shadow of hunger. Almost half of the respondents said that some members of the households had to sleep hungry at some point in the preceding three months, and as many as 10 per cent said that they had gone hungry “many times” in that period. The situation was better among households that had a ration card and a pension, but even they were not exempt from food insecurity. There is a strong case for raising pension amounts and expanding Antyodaya entitlements without delay. Strict action against those who exploit PVTGs would also help. Taking a longer view, PVTG hamlets need better public facilities, especially well-functioning schools and anganwadis. Failing that, PVTG children are unlikely to live much better than their parents when they grow up.

The author is Visiting Professor at the Department of Economics, Ranchi University