The aggressive rise of China is compelling the United States of America to augment its security and diplomatic arrangements in the Indo-Pacific region. In addition to its own presence through the Hawaii-headquartered Indo-Pacific Command, the US has relied, since the 1950s, on its bilateral treaties, principally with South Korea, Japan and Australia, for the region’s defence and security. These pacts have enabled the location of US forces in these countries and, in turn, cover them with an American nuclear umbrella. While these bilateral relationships continue, the US, along with the United Kingdom and Australia, put in place on September 15, according to the joint statement of its leaders, “an enhanced trilateral security partnership called “AUKUS” — Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States”.

The first Aukus initiative is to enable Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines through the transfer of nuclear propulsion technology. Only once has the US given sensitive nuclear technology to any country; in the 1950s, it did so to the UK. Significantly, Aukus declared that its decision was based in recognition of the three countries’ “common tradition as maritime democracies”. Japan and South Korea are also maritime democracies but they have been kept out of this security partnership. At the same time, the UK, which has by now hardly any Indo-Pacific presence, has been brought in. This initiative has led to Australia reneging on its long-standing agreement with France; the European country was to build submarines for it. An enraged France complained it had been stabbed in the back by its allies. Thus, the US has signalled that it can ultimately rely only on its white, Anglo-Saxon, English-speaking brothers to meet China’s security challenge in the Indo-Pacific.

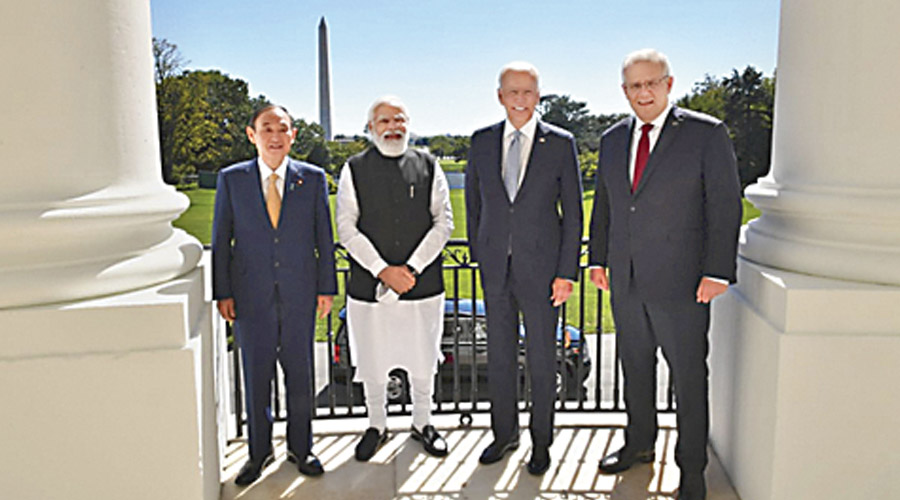

Aukus was announced nine days prior to the first in-person Quad summit held on September 24. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, along with his Australian and Japanese counterparts, joined the US president at the White House. As the essential reason for Quad and Aukus lies in China’s disdain for the norms of the present US-led world order, it was natural for observers to ask if the latter group would undercut the former. The foreign secretary, Harsh Vardhan Shringla, refuted this thought. He said that while Quad is a group of countries with a shared vision of their “attributes and values” and of the Indo-Pacific “as a free, open, transparent, inclusive region”, Aukus is “a security alliance between three countries”. Shringla further asserted that Aukus is “neither relevant to the Quad nor will it have any impact on its functioning”.

Shringla’s distinction between Quad and Aukus is technically correct but inter-state diplomacy is not only about exactitude; it is a game of perceptions too. The feeling in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, even if unspoken or seldom articulated, will be that for the US, the core group to take on China henceforth will be Aukus for, unlike Quad, it will have military and operational teeth. It is true that Quad’s agenda of wide-ranging cooperation with the Indo-Pacific region and its insistence on the observance of norms of global conduct are important for the area, but perceptions are determined more by hard power than by other considerations. This does not detract from the need to meet the challenge of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to create a web of dependencies and generate coercive influence in the region.

China is vigorously and continuously moving into India’s immediate neighbourhood. It is using its vast financial resources to support this ingress. These Chinese actions are detrimental to Indian interests. It is, therefore, natural for India to look to join hands with other Quad countries which share concerns on Chinese behaviour. While doing so, despite the common “attributes and values”, India has to be always conscious that its objective realities and those of the other three Quad countries are vastly different. These objective realities are determined by its stage of development and location. Unlike the other three, it is an emerging economy and a developing country and not an advanced developed country. For this reason, it has to be simultaneously part of the ‘trade unions’ of states and have a seat at the table where the rules of global management are set. Also, it is the only Quad country which has a land border with China. Thus, while it has a coincidence of interests with Quad arising out of China, there are great areas of divergence.

All this requires adroit Indian diplomacy to balance its interests and concerns. Did it succeed in doing so in the drafting of the Quad summit joint statement? India took common positions with its Quad partners on Covid vaccines, climate change, technology and infrastructure development, cyber and outer space, and freedom of navigation. These are global issues that impact Indian interests and on many of them Indian perspectives in view of its objective realities necessarily have to be different from those of the advanced countries, including the other three Quad members. This is not surprising because India’s position on the development ladder necessitates adopting views on economic and technology-related issues that are more aligned with those of the developing world. It is here that India has to protect its interests and bring in more balanced and equitable positions in Quad. It has to do so even while sharing the other three states’ opposition to Chinese practices, which are harmful to Indian and the developing world’s interests as well.

Specifically on the distribution of Covid vaccines, the government has assured that exports will take place taking into account Indian needs. This is reassuring, but the fact is that while the US and Japan have fully vaccinated more than 50 per cent of their populations, and Australia 40 per cent, only 25 per cent Indians have got the double dose till now. So what will be its criterion of Indian requirements? On climate change, can India be more ambitious than it is at present? The compulsions of geography dictate that Indian orientations have to be different from those of the other Quad members on Afghanistan and Myanmar and, yet, the joint statement does not reflect this aspect.

The Quad membership may be desirable but a very heavy price is being paid.

Vivek Katju is a retired Indian Foreign Service officer