|

|

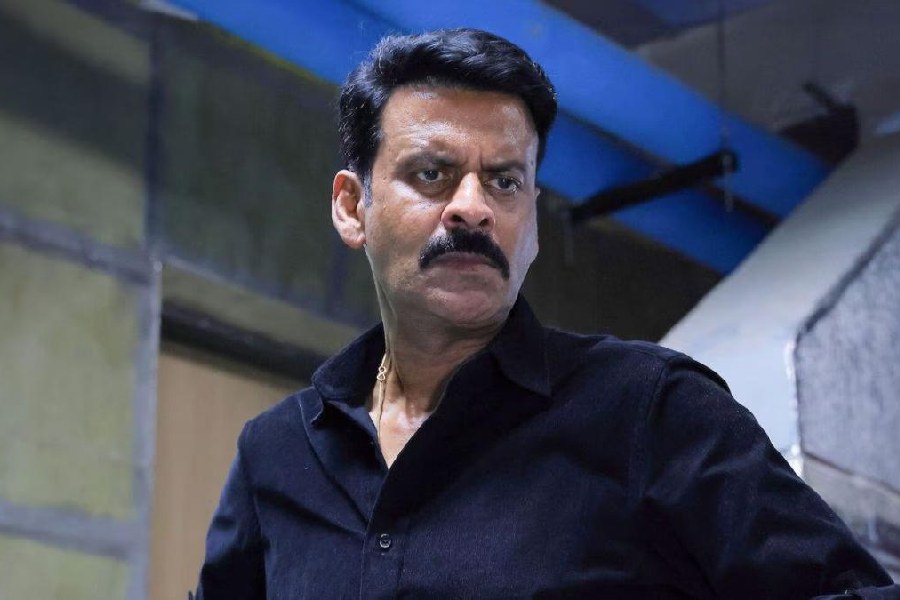

| Making of a hero |

MAO By Michael Lynch, Routledge, Rs 295

On 1 October 1949, a fifty-six-year-old fat, balding peasant named Mao Zedong proclaimed the foundation of the People?s Republic of China from a building in the forbidden city. Mao not only became the ruler of the world?s most populous state, he also became the role model for red revolutionaries of south and south-east Asia.

In this slim volume, Michael Lynch assesses the rise and impact of Mao. In recent times, psychoanalysts have urged for a greater emphasis on the private life of noted personalities in order to understand their public activities. Lynch?s monograph, based on secondary sources, provides a brief glimpse of both Mao?s private and public lives.

While analysing Mao?s career, one has to understand why the Chinese Communist Party won against the better-equipped Kuomintang, which enjoyed the support of both the Soviet Union and the US. The reason was that Mao understood China better than his political rivals. It has been rightly said that Mao was more Chinese than a communist. Instead of abstract Marxist theories, Mao felt attracted to the classical literature of ancient China. Unlike Lenin, Trotsky and Bukharin, who were urban, sophisticated and educated, Mao, till 1950, had never set foot outside China. But Mao had a thorough knowledge of the conditions of the Chinese peasantry.

Mao challenged the Comintern line and forcefully argued that the Russian communist agents had no understanding of China?s internal conditions. Since 90 per cent of China?s population were small peasants, a peasant revolution was more practicable than an urban proletarian revolution. While the Kuomintang focused on cities on China?s coast, the Communist Party won over peasants in the countryside who provided the manpower and logistical support to the communists.

Mao promised land to the peasants, which encouraged them to join the Red Army and fight the Kuomintang. Soldiers of the Kuomintang, on the other hand, were conscripts, torn from their land and families. At the first opportunity, they defected to the CCP with their weapons. Mao emphasized that the Red Army should win over the villagers by behaving well with them. Both the Kuomintang and the Japanese were engaged in plunder and mass rape of the villagers.

Lynch compares and contrasts Mao?s system with the other 20th century authoritarian systems. Hitler, Stalin and Mao were intensely nationalistic. Hitler compared himself with Frederick, Stalin with Peter the Great, and Mao with Qin Shihuang, the aggressive Chinese emperor of third century BC. As Mao grew older, his hunger for sex increased. The chief of his secret police, Kang Sheng, had the task of supplying young women for the Chairman?s bed. Another duty of Kang was to fill the laogais (equivalent to Stalin?s gulags) with anti-Mao dissenters.

Hitler, Stalin and Mao have gone down in history for their bloodthirst. If Hitler killed his victims for their race, Stalin killed for their actions, Mao killed for their thought. The Great Leap of the Fifties and the Cultural Revolution of the Sixties killed 100 million Chinese.

Under Mao, China made progress, but at a horrible human cost. As for the debate whether Mao has put the clock of Chinese history back, the jury is still out. But one thing is clear. By discarding his policies, Mao?s successors have been able to transform China into a mini-superpower. The process of discarding Mao?s policies started after September 1976, when the blind and deaf Mao died a squalid death.